Unlike today, where shipbuilding is based on science and where ships are built using computers and sophisticated tools, shipbuilding in ancient Rome was more of an art relying on rules of thumb, inherited techniques and personal experience rather than an engineering science. The Romans were not traditionally sailors but mostly land-based people who learned to build ships from the people that they conquered, namely the Carthaginians (and their Phoenician predecessors), the Greeks and the Egyptians.

There are a few surviving written documents that provide descriptions and representations of ancient Roman ships concerning the masts, sails and rigging. Excavated vessels also provide some clues on ancient shipbuilding techniques. What studies of these ancient documents and excavated vessels have taught us is that ancient Roman shipbuilders built the outer hull first, then proceeded with the frame and the rest of the ship. Planks used to build the outer hull were initially sewn together. Starting from the sixth century BCE, they were joined together using the locked mortise and tenon method. Then in the first centuries of the current era, Mediterranean shipbuilders shifted to another shipbuilding method, still in use today, which consisted of building the frame first and then proceeding with the hull and the other components of the ship. This method was more systematic and dramatically shortened ship construction times.

Warships

Warships were built to be lightweight, fast and very manoeuvrable. They would not sink when damaged and often would lay crippled on the surface after a naval battle. They had to be able to sail near the coast, which is why they had no ballast and were built with a length to breadth ratio of the underwater hull of about 6:1 or 7:1. They had a ram often made of bronze which was used to pierce the hulls or break the oars of enemy ships. Warships used both wind and human power (oarsmen) and were therefore very fast.

Before the First Punic War which lasted 23 years (264–241 BCE), the Romans had very few warships. Actually, in 311 BCE, a committee was set up to plan for the development of the Roman navy. Back then, Rome only had 20 warships, all of them triremes, while Carthage, with the largest navy in the world, had hundreds of large quinqueremes. It is believed that the Romans copied a Carthaginian quinquereme which ran aground as it tried to block the passage of Roman ships on their way to Sicily. The Romans then managed to build 100 quinqueremes which were, however, heavier and far less manoeuvrable than their Carthaginian counterparts. Eventually, Rome's navy became the largest and most powerful in the Mediterranean and the Romans dominated what they called Mare Nostrum ("our sea").

The trireme was superseded by the larger quadriremes and quinqueremes. The quadrireme had four rows of oarsmen while the quinquereme had five. According to Polybius, the Roman quinquereme had a total of 300 rowers with 90 oars on each side. It was about 45 m long and 5 m wide and would displace around 100 tons. It was superior to the trireme, being faster and performing better in bad weather.

Merchant ships

Merchant ships were built to transport lots of cargo over long distances and at a reasonable cost, therefore speed and manoeuvrability were not a priority. They had a length to breadth ratio of the underwater hull of about 3:1, double planking and a ballast for added stability. Unlike warships, their V-shaped hull was deep underwater meaning that they could not sail too close to the coast. They usually had two huge side rudders (or steering oars) located off the stern and controlled by a small tiller bar connected to a system of cables. They had from one to three masts with large square sails and a small triangular sail called the supparum at the bow.

The Roman merchant ship's cargo capacity usually was between 100 to 150 tons (150 tons being the capacity of a ship carrying 3,000 amphorae). The smallest ships had a capacity of 70 tons while the largest could have a capacity of 600 tons for a length of 150 feet (c. 46 m). Cargo included agricultural goods (e.g. grain from Egypt's Nile valley, wine, oil, etc.), raw materials (iron bars, copper, lead ingots, marble, and granite) and other goods. Just like warships, merchant ships also used oarsmen. Following the collapse of the Roman Empire, no ships of the cargo-carrying capacity of Roman ships were built until the 16th century CE.

NAVIGATION IN ANCIENT ROME

Just like with shipbuilding, navigation in ancient Rome did not rely on sophisticated instruments such as compasses or GPS but on handed-on experience, local knowledge and observation of natural phenomena. In conditions of good visibility, seamen in the Mediterranean often had the mainland or islands in sight which greatly facilitated navigation. They sailed by noting their position relative to a succession of recognizable landmarks and used sailing directions. Written sailing directions (periploi in Greek) for coastal voyages were actually introduced in the 4th century BCE. They were initially written in Greek and they existed for trips in the Mediterranean. By 50 CE, there were written directions not only for the Mediterranean but also for routes from Atlantic Europe to the city of Massilia and for routes along the coast of north-west Africa, around the horn of Africa or past the Persian Gulf to India and beyond.

When weather conditions were not good or where land was no longer visible, Roman mariners estimated directions from the pole star or, with less accuracy, from the sun at noon. They also estimated directions relative to the wind and swell. A lot of the Romans' navigational skills were inherited from the Phoenicians. Pliny claimed that the Phoenicians were the first to apply astronomical learning gained from the Chaldeans to navigation at sea. For example, Phoenician seamen realized that the constellation Ursa Minor orbited the celestial North Pole in a tighter circle than did Ursa Major. As a result, they used Ursa Minor to give them a more precise direction of north.

Both merchant ships and warships used wind (sails) and human power (rowers). Coordinating the hundreds of rowers was not an easy task and in order to solve this problem of rowers' coordination, a musical instrument, usually a wind instrument, would be played. Roman seamen also had to have a good understanding of natural phenomena, wind direction relative to the sail, and they had to know how to operate the sails in various weather conditions.

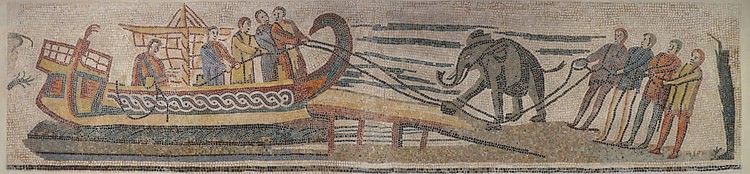

There were a large number of sailing routes with more or less regular schedules in the Mediterranean. Merchant ships would bring supplies from the provinces to the ports of the Italian peninsula. During the Empire, Rome was a huge city (for ancient standards) of about one million inhabitants. Goods from all over the world would come to the city through the port of Pozzuoli situated west of the bay of Naples and through the gigantic port of Ostia situated at the mouth of the Tiber River. For example, 1,200 large merchant vessels (of c. 350 tons) reached the port of Ostia every year or about five per navigable day. Large merchant ships would approach the destination port and be, just like today, intercepted by a number of towboats that would drag them to the quay.

The time of travel along the many sailing routes could vary widely. Ships would usually ply the waters of the Mediterranean at average speeds of 4 or 5 knots. The fastest trips would reach average speeds of 6 knots. A trip from Ostia to Alexandria in Egypt would take about 6 to 8 days depending on the winds. Travel from south to north or from east to west would usually take more time due to the unfavourable winds. It is worth noting that commercial navigation in the Mediterranean was suspended during the four winter months. This was called the Mare Clausum.

CONCLUSION

The ancient Romans built large merchant ships and warships whose size and technology were unequalled until the 16th century CE. Roman seamen navigated across the Mediterranean, Red Sea, and Indian Ocean and out into the Atlantic along the coasts of France, England and Africa. They had an advanced knowledge of navigation and navigated by the sighting of landmarks with the help of written sailing directions and by the observation of the position of celestial bodies, noting that navigational instruments such as the compass, albeit in use in China from the second century BCE, did not appear in Europe until the 14th century CE. During the Empire, there were a large number of busy shipping lanes in the Mediterranean or as the Romans called it Mare Nostrum bringing supplies from the far-away provinces to the ports of the Italian peninsula. Warships of the Roman navy, very fast and manoeuvrable, protected the shipping lanes from pirates. Overall, shipping in ancient Rome resembled shipping today with large vessels regularly crossing the seas and bringing supplies from the four corners of the Empire.