Vulci (Velch) was an Etruscan city located 12 km from the western coast of central Italy by the banks of the Fiora River. Flourishing as a trading port between the 6th and 4th century BCE, it was an important member of the Etruscan League. The archaeological site has yielded many bronze works and a vast quantity of fine pottery, which has filled museums worldwide, but its most impressive contribution to our knowledge of the Etruscans is the many tombs at the site, including the 4th-century BCE Francois Tomb with its vibrant wall paintings.

Early Settlement & Geography

There are few written sources describing the history of Vulci, known as Velch to the Etruscans themselves, but substantial archaeological remains are testimony to its prosperity from the 6th to 4th century BCE. The site had been inhabited since the Neolithic period but was long overshadowed by nearby Tarquinii in the first centuries of the 1st millennium BCE. The wealth of the city was based on three factors: fertile agricultural lands, rich metal deposits in nearby Monte Amiata, and its strategic location on the Fiora River, allowing it to control trade from the coast to inland territories. The city's seaport has been identified by some scholars as Regae.

A Thriving Etruscan City

Vulci did not just prosper as a trade centre passing on goods made by others (especially black-figure and red-figure pottery from Greece – often specifically made for the Etruscan market – and faience flasks from Egypt) but was also a major manufacturing centre in its own right. Fine decorated pottery, the bucchero wares with shiny dark grey surface, bronze work (especially utensils, tripods, braziers, and even chariots), gold jewellery, carved precious stones, wooden boxes inlaid with ivory plaques, bone and ivory spoons, ostrich eggs (imported and then painted by Etruscan artists), and large-scale stone carvings were all produced here. The latter were carved from the local volcanic stone known as nenfro in Vulci's school of stonemasons which influenced other Etruscan cities.

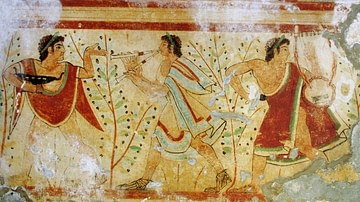

All of these goods were exported throughout Italy and beyond, with Vulci-manufactured wares turning up in tombs across Europe. The high quality of the pottery finds, such items as finely-worked gold jewellery, and the sumptuous adornments and clothes of women depicted in tomb wall paintings all indicate the wealth of Vulci's elite. Further, the general prosperity and cultural pull of the city is illustrated by the presence of such foreign artists as the East Greek 'Swallow Painter,' who set up shop in Vulci and produced there his famous black-figure vases.

Vulci was one of the twelve (or 15) members of the Etruscan League, a loose association of politically independent cities bound together by common religious ties. The other members included Cerveteri, Chiusi, Populonia, Tarquinia, and Volterra, but their exact relationship is not clear. Ancient authors group them together as Etruria or 'the peoples of Etruria,' and the Roman historian Livy describes an annual meeting of city leaders at the Fanum Voltumnae sanctuary near Orvieto. The inability of the Etruscans to form a cohesive political alliance would be an important factor in their downfall at the hands of their aggressive southern neighbours, the Romans.

The city declined along with the Etruscan civilization in general between 450 and 350 BCE when Syracuse gained control of local shipping routes. Nevertheless, the city did recover somewhat, as attested by such artefacts as marble sarcophagi dating to the second half of the 4th century BCE. However, the revival was to be short-lived as the Romans, led by T. Coruncanius, conquered Vulci in 280 BCE. In 273 BCE a Roman colony was founded at Cosa which took over the lucrative trade routes and condemned Vulci first to be made only a municipium in 90 BCE and then eventual obscurity in the following centuries, a situation not helped by the presence of malaria in the region.

Archaeological Remains

The site of Vulci today largely contains remains dating from the 4th century BCE, and so there are very few traces of the structures from Vulci's Etruscan heyday. These include portions of the city walls and a large temple platform which measures 24.6 m x 36.4 m. It once had four columns on the short sides and six along the long sides and was perhaps dedicated to Minerva. There are also the remains of several pottery workshops. A cemetery or necropolis has been an incredibly rich source of finds. These and its large size are indicative of the city's wealth in the Archaic period. Objects excavated include stone funerary sculptures, fine decorated pottery vases – both locally made and imports, – gold jewellery pieces, engraved bronze mirrors, a bronze urn in the form of a hut, and a fine 6th-century BCE bronze tripod with lion's claw feet and figures of satyrs, Hercules and Iole.

The site has also provided two particularly fine 4th-century BCE marble sarcophagi. Each has a tenderly embracing couple carved on the lid while one has scenes of the husband and wife departing in a chariot for the underworld at either end and the second has scenes involving Amazons. Both these coffins are today in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts while many of the finest small-scale Etruscan art pieces are to be found in the Museo Etrsuco di Villa Giulia in Rome.

The Tombs of Vulci

The larger tombs at Vulci were guarded by stone sculptures of Greek monsters such as centaurs, sphinxes, rams and winged lions, but it is their interiors which are of special interest. The 6th-century BCE tomb of 'Isis' was excavated by Napoleon's brother Lucien Bonaparte in 1839 CE, and it contained many fine artworks (now mostly at the British Museum). These include a hammered bronze bust of an unidentified goddess holding a horned bird, an 89 cm tall statuette of a standing woman, and a stamped gold sheet diadem. Another tomb, the Tomb of the Bronze Chariot, contained a 7th-century BCE embossed sheet bronze chariot.

The Tomb of the Warrior dates to around 510 BCE and is so-called because of the bronze armour and weapons found therein. There was a large bronze shield, a Negau-type helmet decorated with images of the river god Achelos and a crest holder shaped in the form of the Dioscuri, greaves (shin protectors), a bronze sword with iron scabbard, and two spears. In addition, there was an entire banqueting set of bronze vessels and utensils – evidence of the Etruscan custom where leaders offered their followers free banquets as a symbol of their power and status.

Most spectacular of all the tombs is the late 4th-century BCE Francois Tomb with its painted walls, showing lively scenes from Greek and Etruscan mythology, various battle scenes with the Romans, and the Vulci rulers fighting against those of the rival Etruscan towns of Volsinii and Sovana. There are funeral games where prisoners are sacrificed in gladiator matches, and one fresco shows a man named in an inscription as Vel Saties, perhaps the occupant of the tomb. The figure, possibly a magistrate, wears a dark blue embroidered cloak and is accompanied by a dwarf holding a woodpecker attached to a string. The bird is about to be released and Vel Saties looks on, perhaps as he is about to follow it in a metaphor for his passage into the next life.