Vardhamana (l. c. 599-527 BCE), better known as Mahavira (“Great Hero”) is the sage credited with founding of the nontheistic religion of Jainism, a belief system established in the 6th and 5th centuries BCE in India, which provided adherents with a disciplined path toward spiritual liberation.

According to Jain tradition, however, he is not the founder of the religion but only the 24th tirthankara (“ford builder”) of the faith who inherited the vision from his predecessors and established it in its present form. Jains believe that the tenets of the faith are ancient, older than Hinduism, and were “received” by the earlier tirthankaras who taught them to disciples and handed them down through the generations.

According to Jain tradition, Vardhamana was born of the warrior (kshatriya) caste to a royal family, grew up in luxury as a prince and heir-apparent, and renounced it all when he was 30 years old after the death of his parents. He went to the woods to live as a spiritual ascetic and, after 12 years of intense meditation, fasting, and denial of the flesh, achieved omniscience while sitting beneath a Sala tree on the banks of a river. After his enlightenment, he began to preach what had been revealed to him, attracting disciples, and establishing his philosophical school, which, at the time, was simply one among many others. Jainism was popularized by royal patronage, especially by the early Mauryan Empire (322-185 BCE), and continued to gain adherents afterwards. In the present day, Jains continue to reside mainly in India but have established communities around the world.

Historical Background

Scholars agree that Vardhamana existed and was an older contemporary of Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha, l. c. 563-483 BCE), but details of his life are largely legendary. He was born in a time of significant social and religious reformation and began the efforts which established Jainism as a reaction to perceived problems with the dominant Hindu faith in meeting the spiritual needs of the people of his time. This was an era of transition and change; urbanization was transforming agrarian communities of small villages and towns into cities, and people were questioning accepted paradigms of religion. This period was, in the words of scholar Jeffrey D. Long, a kind of Indian “Protestant Reformation” in which the monolithic tradition of Hinduism, previously accepted as truth without question, was challenged.

Hinduism was based on an acceptance of the Vedas, the Hindu scriptures, which were thought to have been received by sages – directly from the universe – in the distant past. These works were, therefore, the authoritative words of God, not to be questioned, and were recited by the Hindu priests and interpreted by them for the people. The Vedas, however, had been delivered and understood in Sanskrit – a language the common people did not understand – and the priests did not seem to be offering anything by way of interpretation or assistance.

During Vardhamana's time, this paradigm was challenged by a number of thinkers who claimed it was no longer acceptable for Hindu priests to claim absolute knowledge of eternal truths. Many different schools of thought developed during this time and, among them, were Charvaka, Jainism, and Buddhism. These three schools are known as nastika (“there does not exist”) because they were heterodox and rejected the authority of the Vedas. Other schools, which accepted the Vedas and the practices of the Hindu priests are known as astika (“there exists”) and were considered orthodox.

The school of Charvaka claimed that truth could not be known except by direct, personal, perception. Hearsay was not considered valid in establishing truth. Since no one could apprehend Truth or relay it accurately, the only appropriate response was to pursue pleasure as the ultimate goal in life. Vardhamana, however, disagreed and preached a vision which was intended to provide an adherent with direct, individual, spiritual transformation as long as one maintained the necessary self-discipline. In opposition to Charvaka, the Jain vision emphasized the importance of faith in pursuing one's path toward liberation and rejecting the temptations of worldly pleasure.

Jainism also rejected the Hindu concept of liberation which claimed that one's immortal soul had to endure a series of incarnations as one worked through past actions (karma) by performing one's duty (dharma) according to one's caste. The highest caste was that of the Brahmins (priests), then Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaishyas (merchants), and Shudras (laborers), with the Dalits (handlers of offal) at the bottom. By performing one's dharma in accordance with one's caste, one would move up the hierarchy in one's next life to finally achieve union with the oversoul (atman) and attain liberation. Vardhamana claimed one could accomplish the same in a single lifetime through adherence to Jain tenets and discipline.

Early Life & Renunciation

Although Vardhamana is presently cited as the founder of Jainism, Jain tradition rejects this claim and maintains that he is only the most recent tirthankara to have received a timeless vision. Scholar Jeffrey D. Long comments:

According to Jainism – and, indeed, all of the major Indic traditions – the universe is a beginningless and endless process, passing through an ongoing series of cosmic cycles, each of which is billions of years in duration. During each cycle, or kalpa, according to the Jain version of this model, 24 Tirthankaras appear. Mahavira, as the 24th Tirthankara of our current cycle, is not, therefore, strictly speaking, the founder of Jainism, but rather its re-discoverer and re-initiator, after the path had declined during the period between his time and the time of his predecessor, the 23rd Tirthankara, who was named Parsvanatha. (Jainism, 29)

Parsvanatha (l. c. 872 - c. 772 BCE) is the first historically attested figure among the tirthankaras preceding Vardhamana. He, like Vardhamana, is said to have been born to royalty, enjoyed an upper-class upbringing, and renounced his wealth and position at the age of 30 to become a religious ascetic. He attained enlightenment beneath a dhaataki tree in Benares and then went on to preach his vision of how one could live an ordered and peaceful life, without suffering, for the next 70 years. Vardhamana's life follows this narrative closely.

It should be noted before the story of Vardhamana's narrative is given that his place of birth, range of influence, and site of death are disputed as are the details of his life. Jainism, after Vardhamana, split into two major schools of thought (there are others), the Digambara (“sky-clad” whose monks go without clothes) and the Svetambara (“white-clad” whose clergy wears white, seamless clothing), both of which claim to hold the “true” Jain vision. The well-known story of Vardhamana's early life, renunciation, and enlightenment is understood as true by the Svetambara sect but is rejected by the Digambara.

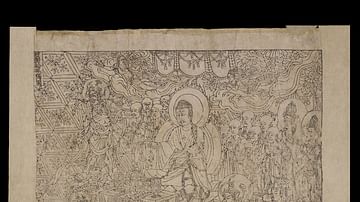

Vardhamana's story first appears in the text known as the Acaranga (3rd-2nd century BCE), some 300 years after he died. According to the Svetambara tradition, he was born in March or April of 599 BCE, the son of King Siddhartha and Queen Trishala who both were adherents of Parsvanatha's vision of truth. He was singled out for greatness at his birth when the god Indra appeared to anoint him and carry him to the heavens to consecrate him to his mission as a religious sage. Bright spirits and various deities are said to have sung at his birth and he radiated light and a sweet scent. When he was returned to his parents afterwards, they and everyone around them prospered and so they named the newborn Vardhamana (“prosperous”).

In his youth, he is said to have performed great feats such as rescuing his playmates from a large serpent without harming it and later saving them from a demon who at first appeared as one of them. According to some legends, this is when he first was called Mahavira for his heroics. Once he was older, as a prince, he was expected to engage in the hunt but refused, claiming that one should treat all living things as one would wish to be treated, and so was released from the obligation.

He lived in his parents' palace in luxury until they died shortly before his 30th birthday. Sometime after this event, he renounced his position and wealth and left his kingdom to live as an ascetic in the woods. He fasted to extremes, exposed himself to the elements, mortified the flesh, and rejected every temptation offered to turn back from his goal of attaining enlightenment. After 12 years of ascetic discipline, he attained complete omniscience at the age of 43 as he sat beneath a Sala tree.

Tenets & Teachings

The Digambara school claims that, after his liberation, he relayed his message non-verbally and continued as an ascetic. The Svetambara, however, maintain that he taught like any other sage, traveling through the country with eleven disciples known as the Ganadharas, the chief of whom was Gautama Swami, the scribe who would later write down his master's teachings.

The central problem Jainism sought to address was suffering caused by the cycle of repeated rebirths and deaths which the soul was trapped in due to an accumulation of karmic matter. Unlike Hinduism and Buddhism, which define karma as action, Vardhamana understood it as matter, a kind of pollution which clings to and clouds the soul, keeping it from recognizing its true nature as well as the nature of existence.

Karmic matter attaches itself to the soul simply owing to the nature of the soul but, as the soul continues to be reincarnated and keeps attaching itself to sense objects, it draws to itself more and more karmic matter and becomes increasingly dull and unaware of itself. Scholar John M. Koller comments:

In its pure state when it is not associated with matter, [the soul's] knowledge is omniscient, its bliss is pure, and its energy unlimited. But the matter that embodies the soul defiles its bliss, obstructs its knowledge, and limits its energy. (33)

To free one's self from this matter, one needs to reject attachments to sense objects and the illusions one accepts as reality. The Jain vision of how to accomplish this is a spiritual discipline proceeding from the Five Vows (fully articulated in the foundational text known as the Tattvartha Sutra, composed 2nd-5th centuries CE) which are intended to inform one's thoughts and behavior, encourage non-attachment to the transient things of this world, and allow one to lead a morally pure life which will free one from the cycle of rebirth and death. The vows are:

- Ahimsa (non-violence)

- Satya (truthfulness)

- Asteya (non-stealing)

- Brahmacharya (chastity or faithfulness to one's spouse)

- Aparigraha (non-attachment)

The Five Vows provide a firm foundation for an adherent to embark on a path of 14 steps which would lead one to liberation. At Step 1, the soul is a slave to passions and ignorance and cannot recognize itself. It knows it is in a state of suffering but is unable to break free because it is so deeply mired in illusion. It makes various attempts at Steps 2-4 and then, at Step 5, takes the Five Vows and begins to restrain itself. In Steps 6-12, the soul works to overcome spiritual lethargy, increase self-awareness, and discard hurtful karma through mindful living and a reflective life. By Step 13, one has mastered detachment from the things of life, even attachment to and identification with one's own body. At Step 14, one has achieved the liberation of transcendent wisdom (moksha) and, when one dies, is never again reborn. Vardhamana, and the tirthankaras who preceded him, all attained Step 14 but, instead of allowing themselves to pass on from the physical world to bliss, remained to teach others how they could liberate themselves as well.

Many-Sided Reality

Central to the soul's ability to detach itself from sense objects – especially one's attachment to one's body – is the recognition that reality is not uniform and cannot easily be defined owing to the individual's subjective limitations. One may define a chair, for example, as “made of wood, four straight legs, a curved back with spindles” and discuss chairs with others based on one's definition only to be surprised when other people define a chair as “large, soft, short-legged, with cushions”. If one is discussing chairs, this might not be a matter of great consequence, but it becomes more important when one is dealing with the definitions of Truth or Justice or God. Insistence on one's own definition of anything attaches the soul more directly to the physical world through identification with the self-as-body, with the identity one has constructed through experience.

Vardhamana stressed the importance of anekantavada (many-sided reality) in addressing this situation; a concept famously illustrated through the parable of the elephant and the five blind sages. A great king asks five blind sages into a room where an elephant stands and asks them to define it. The first feels the trunk of the elephant and defines it as a snake; the second feels of the tail and claims it is a rope; the third places his hand on a leg and says the animal is a tree trunk; the fourth caresses an ear and says an elephant is like a fan, while the fifth touches its side and declares the others are wrong and the elephant is like a wall.

In this same way, people apprehend only a small part of reality, claim their vision is the correct one, and then, instead of listening to and trying to understand other definitions and visions, continue to assert their own rightness. In doing so, the individual attaches more and more karmic matter to the soul in maintaining what the iconic psychologist Carl Jung would call a “fixed persona”, complete identification with the sort of person one believes one's self to be, and remains a slave to one's ignorance and passions. Recognizing the many-sided nature of existence frees one to explore other possibilities than one's own of how the world works or what constitutes a chair or elephant and makes it easier to recognize irrelevancies in one's life and let them go, aiding in detachment and greater peace of mind.

Conclusion

Vardhamana preached the Jain vision for 30 years after attaining liberation, traveling naked through the country as he had even renounced the need for clothing. In guiding others on the path to enlightened living, he emphasized the Five Vows and 14 Stages in conjunction with the concepts known as Ratnatraya, the Three Jewels:

- True Faith

- Right Knowledge

- Pure Conduct

The last of these stressed respect for all living things and doing no intentional harm to any, no matter how justified one may feel violence is in the moment. His insistence on ahimsa as the best response to other people's aggression would later influence Mahatma Gandhi (l. 1869-1948 CE) in his efforts to liberate India from British rule and Gandhi's efforts would inform those of Dr. Martin Luther King, jr. (l. 1929-1968 CE) in the Civil Rights Movement in the USA of the 1950s and 1960s CE.

Vardhamana continues to be venerated in the present day through the Jain festivals of Mahavir Janma Kalyanak, celebrating his birthday, and Diwali (not the same, but held at the same time, as the Hindu festival), a recognition of the day of his enlightenment, which is also New Year's Day for Jains. Jain temples honor him with statuary, and he is included in prayers of gratitude for his efforts in awakening humanity to the possibility of a higher way of understanding and living life.