Tintoretto (c. 1518-1594 CE), real name Jacopo Robusti, was an Italian Renaissance artist who specialised in religious, mythological, and portrait paintings. A prolific artist over a long career, the Venetian's masterpieces are famous for their light, vibrant colouring, and dramatic composition. Major works include St. George and the Dragon, now in the National Gallery in London, and his cycle of paintings for the Scuola di San Rocco in Venice. Tintoretto's originality, energetic figures, and technique of using quick sketches in chalk and paint would be hugely influential on 17th-century CE artists.

Early Life & Style

Tintoretto was born in Venice c. 1518 CE, his given name being Jacopo Robusti. He acquired his more famous nickname because his father was a dyer (tintore), and Tintoretto means 'little dyer'. Appropriately enough, the artist would become famous for the vibrant colouring in his work. Indeed, a motto commonly attributed to him is "Michelangelo's drawing, and Titian's colour" (Hale, 315), showing two of the biggest artistic influences on his work. The artist began with modest works like decorated furniture and frescoes for exterior walls, but it would be paintings, often very large canvases, that became his forte.

According to Carlo Ridolfi, who wrote his biography of Tintoretto in 1648 CE (Le maraviglie dell'arte), the young artist studied under his fellow-Venetian Titian (c. 1487-1576 CE), and it is true that his paintings do combine the dramatic postures and composition seen in the work of Michelangelo (1475-1564 CE) and the rich colours used by Titian. Tintoretto, though, was a superb draughtsman, and here he differed from his one-time master, who preferred the technique of colore (or colorito), that is using the juxtaposition of colours to define a composition, to that of disegno, the technique which emphasised the importance of defining form using lines. Ridolfi mentions that Titian and Tintoretto's relationship was a stormy one, and perhaps this divergence of technique, colour versus line drawing, was the source of much dispute.

Another feature of Tintoretto's artistic style is the light source, which often creates unusual and dramatic areas of colour and shadow in the scene. The effect was achieved by the artist first creating a miniature wax model of the human figure he wanted to paint and assembling a number of these models inside a box. The models could then be moved around and an artificial light source arranged in different positions to create different and unusual effects of light and shadow. The energy that Tintoretto then instilled in his muscular figures with their unusual poses - what would become known as the Mannerist style or Mannerism - and the rapidity with which he sketched using chalk or paint in order to capture the fluidity of movement of the human body, all acted as a major influence on artists who followed in the 17th century CE. During his own career, however, the speed at which Tintoretto painted and the sometimes lack of finish in his work was a frequent source of criticism.

Tintoretto first gained notice after painting a large series of octagonal ceiling panels with mythological scenes in a private Venetian palace. This was followed up with a series of frescoes for Palazzo Zen in the same city, this time in collaboration with Andrea Meldolla (aka Schiavone). Unfortunately, only fragments of these frescoes survive but the technique, a fast one made necessary by the rapidity of the paint drying, must have interested Tintoretto as his later paintings often show the same quick brushstrokes, at least in the final layers of the work.

The Tintoretto Workshop

In 1555 CE Tintoretto married Faustina Episcopi, with whom he had eight children. For the next decade the artist was occupied with paintings with a biblical theme for Venice's Madonna dell'Orto church. Tintoretto remained in Venice for most of his career where he won commissions from various civic authorities, charitable institutions, and the Doge (ruler) of the city. The Venetian painter ran a large workshop to cope with the demand, overseeing the production of paintings on all manner of religious subjects, although allegorical pieces seemed to be his favourite. The artist's fame ensured that his workshop was visited by artists from far and wide, including from the Netherlands and Germany. It was also at this workshop that Tintoretto trained his son, Domenico Tintoretto (c. 1560-1635 CE) who later became a famous painter in his own right, particularly of portraits. Two more of Tintoretto's children were apprentices, his son Marco (1561-1637 CE) and daughter Marietta (c. 1556-1590 CE). Domenico certainly worked on a number of pieces with his father, and it was he who carried on running the workshop when his father died in Venice in 1594 CE. Tintoretto was buried in the church of Madonna dell'Orto.

Major Works

The Miracle of St. Mark

Tintoretto's paintings can be broadly divided into three main areas: religious subjects, mythological allegories, and portraits. In 1548 CE Tintoretto produced his celebrated Miracle of Saint Mark Rescuing a Slave, now in the Academia of Venice. Commissioned by the Confraternity of San Marco, it is a triumph of light and darkness and surprised its audience with its energy and drama. The falling, twisting depiction of Venice's patron saint in the centre of the picture is highly unusual for a painting and seems more fitting for a ceiling fresco. It is a clear influence from Michelangelo's work. The writhing crowd provides another source of hectic movement, the figures arranged, as so often in Renaissance art, into an approximate triangle. The naked martyr in the foreground is foreshortened and leads the viewer's eye irresistibly into the crowd. In a typical example of Renaissance artistic deference to patrons, the chief officer of the confraternity, one Tomasso Rangone, appears in the bottom left corner of the painting. However, the fact that the confraternity did not take possession of the painting until 14 years after its completion suggests the work was rather too radical for immediate acceptance.

Around 1555 CE Tintoretto produced another masterpiece, Susanna at her Bath, which shows the story of the biblical figure who bathes while being spied upon by two old men. The naked figure of Susanna and the silver-coloured elements of the composition are strikingly bright compared to the gloomy elements of the background.

Saint George & the Dragon

The Saint George and the Dragon painting, produced around 1570 CE, is another of the great masterpieces. The scene displays typical features of Tintoretto's style. Firstly, the background landscape seems to drift off into infinity, stretching the scene out and bringing the human figures closer to the viewer. The white-walled city at the very back of the painting is painted in such a vague way that it seems unreal. Then, the two figures in the painting are simply bursting with energy. Further, both figures seem to be off-balance. Saint George is falling to the left and slightly away from the viewer while the female figure in the foreground seems to be falling forward towards the viewer as she flees the dragon. The tension caused by this polar movement is something that can be seen in many of the artist's paintings. Finally, the light shining from the angelic figure in the sky above is so arranged as to resemble a stage spotlight, reminding of the artist's technique of using miniature wax models. A near-contemporary painting of the Saint George is The Origin of the Milky Way, now in the National Gallery in London.

The Scuola di San Rocco

While still producing such paintings mentioned already, Tintoretto's major commission, perhaps his greatest life's work, was the series of oil on canvas paintings in the Salla dell'Albergo and lower hall of Venice's Scuola Grande di San Rocco. Scuole were charitable organizations, and the San Rocco one was able to afford such lavish decorations because it was doing rather well from public contributions. This was because Saint Rocco was considered a great protector against the Black Death, then ravaging Europe for the umpteenth time. Tintoretto had won the competition to see which artist would decorate the scuola by secretly going into one of its rooms and hanging up one of his paintings. The artist was also a member of the confraternity, and this, along with a promise to give some paintings for free, must have helped his bid for the contract. A special three-man committee was, nevertheless, set up by the scuola, in order to examine and judge if each painting was worthy of inclusion.

Begun in 1564 CE, Tintoretto continued to work on the room for the next 17 years. The finished works were hung on the walls and from the ceiling, and they show scenes from the Old Testament, the life of Jesus Christ, and episodes involving the Virgin Mary. The works include the massive 12.2 metres (40 ft) wide canvas the Crucifixion, the Christ before Pilate, and Moses Drawing Water from the Rock. The figures in these works are remarkable for the lighting, distorted perspectives, and relentless action within the scenes.

The original ideas Tintoretto produced for the scuola led the famed art historian Giorgio Vasari to comment in the 1568 CE update of his The Lives of the Most Excellent Italian Architects, Painters, and Sculptors, that Tintoretto was "the most extraordinary brain that the art of painting has produced." (Pallucchini). And this was when Vasari had still not seen the completed works. When finally finished in 1581 CE, Tintoretto had given the Scuola 18 painted ceiling panels and 10 large paintings which functioned admirably as a pictorial narrative of the most important episodes of the Bible.

Doge's Palace & Portraits

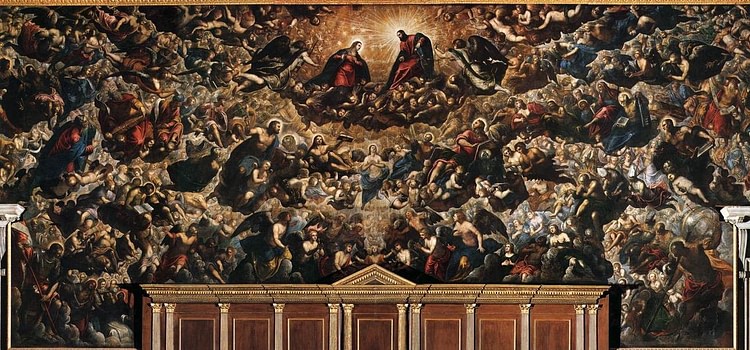

In 1588 CE the Italian painter completed one of many commissions for the Doge of Venice, the Paradise painting. This was the largest canvas he ever produced and was hung across one entire wall of the Great Council Hall. However, now over 70 years of age, it is very likely many of the works for the palace were executed or completed by suitably qualified members of Tintoretto's workshop. One of the final masterpieces was the celebrated Last Supper painting for the church of S. Giorgio Maggiore. Worked on between 1592 and 1594 CE, the Last Supper is recognised as a tour de force of Mannerism.

Like many successful Renaissance artists, Tintoretto was frequently called upon to produce portraits of the rich and powerful. Two examples are his representation of Doge Alvise Mocenigo, r. 1470-77 CE (Academia, Venice), and the nobleman Vincenzo Morosini (National Gallery, London). He even found time for a self-portrait or two, one of which is now in the Louvre, Paris.