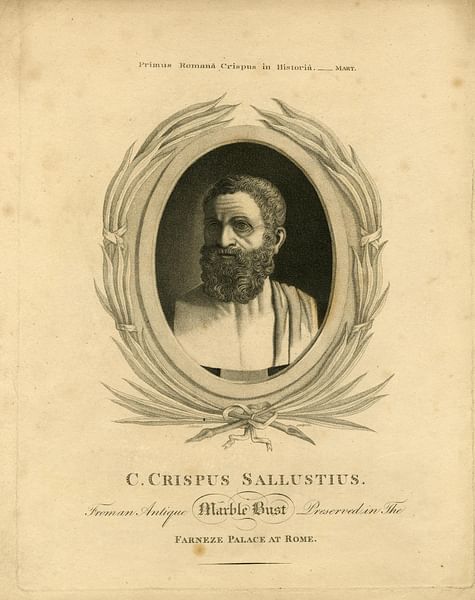

Gaius Sallustius Crispus (86-35 BCE), better known as Sallust, was a Roman statesman and historian. He turned away from an unsuccessful career in both politics and the Roman army, choosing instead on a writing career and produced three major works: Bellum Catilinae (Catiline's War), Bellum Jugurthinum (Jugurthine War), and Histories. Unfortunately, his works would almost be forgotten under decades later. His writing style and perspective would influence American and well as 17th-century English politicians.

Early Life & Political Career

Sallust was a Sabine from Amiternum, born in 86 BCE. Other than the speculation that he may have been a member of the local aristocracy, little is known of his early life. He rose to prominence in Roman politics, military, and historiography. His somewhat humble origins would influence both his writing and historical perspective. While no one in his family had ever been involved in politics, he accomplished the unthinkable when he became a tribune of the plebs in 52 BCE. In his first major work Bellum Catilinae, he wrote on his reason for entering politics and the shock at what he found:

I, myself, however, when a young man, was at first led by inclination … to engage in political affairs, but in that pursuit many circumstances were unfavorable to me, for instead of modesty, temperance, and integrity, there prevailed shamelessness, corruption, and rapacity. (9)

This disgust would become a major theme throughout his writing. It was the time of Julius Caesar's (100-44 BCE) war with Pompey (106-48 BCE), and Rome was a city on edge. During these hectic days of the Roman Republic, tribunes had gained considerable political power in the Roman government, and Sallust took full advantage of this. Unfortunately, his vocal outbursts against the famed orator and statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BCE) and politician T. Annius Milo (95-48 BCE) would eventually lead to his expulsion from the Roman Senate in 50 BCE.

Milo, a candidate for consul and rival of Julius Caesar, was on trial, having been accused of orchestrating the murder of the unscrupulous politician Clodius Pulcher (93-52 BCE), a candidate for a praetor. At the trial Cicero defended Milo, but Sallust and his fellow tribunes spoke out against him, verbally attacking Cicero. Unfortunately for Milo, he was found guilty and exiled. After only two years as a tribune, Sallust was charged with immorality and expelled; however, most believe it was his actions against the highly influential Cicero that had led to his dismissal.

His close friendship with Julius Caesar saved him, and while he had little if any military experience, he was given the unsuccessful command of a legion in 49 BCE. Two years later, in 47 BCE, he tried and failed to quell a mutiny, but, in 46 BCE, as a praetor, he had some success in Caesar's African campaign. As the governor of Africa Nova, he was charged with malpractice; namely, extortion and plundering. Again, Caesar came to his rescue, and Sallust avoided a trial.

He would later write of his ineffective political career that he had detested the dishonest practices he saw in politics but was lured by ambition and the same "eagerness for honors" (Bellum Catilinae, 9). According to historian Barry Strauss in his The Death of Caesar, Sallust suggested to Caesar that he should strengthen the Republic for the future not only in arms to use against Rome's enemies but also in the "kindly arts of peace" (31). There is no mention of how Caesar received this suggestion. After his failures in politics and the military, Sallust decided, and rightfully so, to end his lackluster career and turn his attention to writing. His decision to leave just happened to coincide with Caesar's assassination in 44 BCE.

Writing Career

In his first book Bellum Catilinae (Catiline's War) he speaks of his decision to turn to writing.

When, therefore, my mind had rest from its numerous troubles and trials, and I had determined to pass the remainder of my days unconnected with public life; it was not my intention to waste my valuable leisure in indolence and inactivity, or engaging in servile occupations … but returning to those studies from which, at their commencement, a corrupt ambition had allured me. (10)

With a mind influenced, in his words, by hope and fear, he wanted to write on "the transactions of the Roman people" (10). For his first effort, he decided to write "with as much truth as I can" on the Catiline Conspiracy because of the "nature of its guilt and perils" (10).

Although the book covers the conspiracy charges against Lucius Sergius Catilina (Catiline), he took the opportunity to discuss what he identified to be wrong with Rome: its moral decline. In his mind, this decline began after the fall of Carthage in 149 BCE and escalated after the dictatorship of Sulla (82-79 BCE). In December 63 BCE Catiline stood before the entire Roman Senate. He was portrayed by his accuser, Cicero, as an ambitious man who had attempted to seize power for his own personal gain. The discovery of the conspiracy would be the highpoint of Cicero's long and distinguished career in politics. The plot conceived by Catiline called for the assassination of several elected officials and the burning of the city itself. The resulting chaos would allow Catiline to assume the leadership role he so passionately desired. He was not alone in his scheme but was supported by disgruntled veterans of the Roman army and the poor (who were promised the elimination of their debt) as well as many who, like Catiline, had hoped for financial gain.

Sallust viewed Catiline as a revolutionary and accepted Cicero's judgment. However, Sallust wrote that Catiline, while a man of noble birth, was "of a vicious and depraved disposition" (11). Although he had a mind that was daring and subtle, he coveted other men's property and sought objects that were unattainable. Although eloquent, he was a man of little wisdom. Sallust believed that the dictatorship of Sulla led Catiline to take the opportunity to seize the government. He wrote that the corrupt morals of the state with its extravagance, selfishness, and destructive vices furnished him with additional incentives to take action.

Past personal history probably kept the author from giving Cicero the recognition he deserved, for Sallust credited Caesar and Cato as the true heroes for the stirring speeches they made during the hearing before the Senate. Caesar, a one-time friend of Catiline, asked that the Senate not act in haste and await the results of a trial. Cato, on the other hand, agreed with Cicero and wanted immediate execution. Caesar's wishes were ignored, and the conspirators were executed without a trial. Catiline, after a failed escape attempt, died during his recapture.

The plot represented another chapter in the decline of Rome. According to the historian Mary Beard in her SPQR, the Catiline conspiracy was emblematic of the failings of the city in the 1st century BCE. The "moral fiber of the Roman culture" had been destroyed not only by the city's defeat of their rivals and domination of the Mediterranean Sea but also by the city's wealthy and their greed and lust for power (Beard, 28). All of this arose after the defeat and destruction of both Carthage and Corinth (146 BCE). Sallust wrote that the republic had increased its power "by perseverance and integrity" (Bellum Catilinae, 19). Powerful princes had been defeated, barbarous tribes were reduced to domination, and "Carthage, the rival of Rome's dominion, had been destroyed, and sea and land lay everywhere to her sway." (19) The long history of the city was seen as a desire for power. "At first the love of money, and then that of power, began to prevail, and these became, as it were, the sources of every evil." (19) This greed undermined both honesty and integrity and replaced them with inhumanity, contempt for religion, and general decadence.

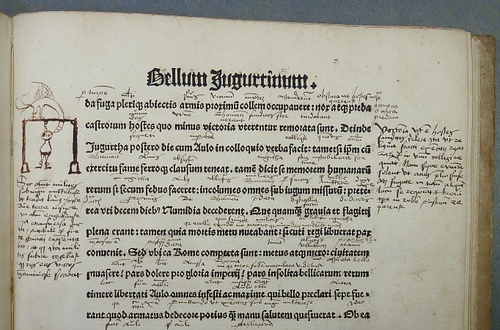

Sallust wrote two more books: Bellum Jugurthinum (Jugurthine War) and Histories. Written between 42 and 40 BCE, the Jugurthine War continued the basic theme of all of his works: the decline of both virtue in Rome and political conflict: the clash of the Senate (nobility) and plebians. Jugurtha was the king of Numidia and had rebelled against Rome in the final years of the 2nd century BCE. Sallust wrote:

I propose to write of the war the people of Rome waged with Jugurtha, king of the Numidians: first, because it was long, sanguinary and of varying fortune and secondly, because then for the first time resistance was offered to the insolence of the nobles. (Bellum Jugurthinum, 141)

Sallust blamed the mishandling of the war on the political struggle prevalent in the Roman Senate. There were charges of both incompetence and corruption. The elitist nobility chose to sacrifice for the sake of their own greed. After a brief visit to Rome, Jugurtha saw Rome as a city for sale "and will fall as soon as it finds a buyer" (Beard, 266). A necessary change came in the form of a "new man" – Gaius Marius. Marius' rise to power as consul was seen as an attack on the political elite. In raising an army he ignored property qualifications and enlisted many of the impoverished Romans. In the end, Jugurtha was finally defeated and brought to Rome in chains where he died in prison.

Although there was some reference to earlier events, his Histories, of which only fragments remain, mostly cover Roman history from 78 BCE to around 67 BCE. Its style demonstrates his respect for the Greek historian Thucydides. As in his other two works, Sallust continues to speak of political conflict and the decline of Roman morality. After the ousting of the king, the nobles began to treat the plebians as slaves "making decisions about their lives and bodies in the manner of kings" (Histories, 1.10). However, they achieved some rights through the tribunes and the plebian assembly. The Punic Wars would temporarily end the discord; however, after the war, this dispute resumed. Again, he returns to a common complaint: the destruction of Carthage. "Discord, avarice, ambition and all the other evils which arise from great good fortune, increased after the destruction of Carthage." (Histories 1.10)

Legacy

Sallust died around 35 BCE. Although many charge his works with inaccuracies and prejudice, his writing style and political perspective influenced both the American founding fathers as well as the English politicians of the 17th century CE. In England, it was the era of unrest and the Glorious Revolution, while in America, it was the time of revolution. Both believed in a government similar to that of the old Roman Republic.