Sir Richard Grenville (1542-1591 CE) was an Elizabethan adventurer, mariner, and privateer whose life story is as entertaining as any fictional sailor. His early career saw him become a Member of Parliament, a soldier in Hungary, and a plantation owner in Ireland. Grenville took the first English colonists to North America in 1585 CE, battled the Spanish Armada in 1588 CE, and then famously fought the Spanish again in 1591 CE, this time in his ship the Revenge in the Azores. The Revenge, fighting alone against a fleet of 56 Spanish ships, sank two of the enemy vessels and damaged many others but eventually succumbed, and Grenville died of his wounds. The episode became the stuff of legend and was celebrated in art, literature, and sea lore for centuries thereafter.

Early Life

Richard Grenville was born in Bideford in Devon, England in 1542 CE, the son of Roger Grenville, a member of the local gentry. Richard's nautical connections began with the death of his father, drowned in the infamous sinking of the Mary Rose, the flagship of Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547 CE). The ship capsized in the harbour of Portsmouth in 1545 CE with the loss of 500 lives. Richard spent part of his education at London's Inns of Court, a collection of institutions that mixed a legal education with the function of a finishing school.

Like many of the Elizabethan period's most famous mariners, Grenville often sailed across the line of the law. In 1562 CE, Richard was pardoned after he had participated in a London riot and killed a man. The young man's respectability seems not to have been tarnished as he attended Parliament in 1563 CE. Three years later, Richard was off to Hungary where he fought against the Turks. Restless legs next took him to the Munster region of Ireland in 1568 CE where he settled on a plantation with his family. This project came to an end with the start of the Fitzmaurice rebellion in 1569 CE. Although Richard stayed on to help reassert English control in the province, his own plantation was destroyed. By 1571 CE Richard was back in England and Parliament where he represented Cornwall.

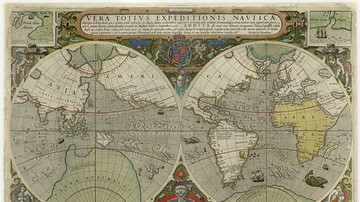

In 1574 CE Richard got together a consortium of Devon businessmen to fund an expedition he would lead to find the fabled great southern continent (both Australia and Antarctica were then unknown to Europeans). However, Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603 CE) was concerned about infringing on Spanish territorial claims in South America and the man with control of the country's purse strings and chief minister in the government, William Cecil, Lord Burghley (1520-1598 CE), said no. Burghley was more interested at that time in finding the Northwest Passage that might permit a short sea route from North America to Asia and so he funded instead an expedition led by Martin Frobisher (c. 1535-1594 CE) for that purpose. The exploration of what lay south of the equator was left to Sir Francis Drake (c. 1543-1596 CE) later in the decade. The first half of Grenville's life showed promise, then, and was certainly exciting enough but it would pale in comparison to the colourful adventures of the second half.

North America: Virginia

In 1585 CE Grenville commanded the fleet which sailed to North America carrying a group of England's first New World colonists. The expedition was masterminded by Grenville's cousin Sir Walter Raleigh (c. 1552-1618 CE) who had named their destination Virginia in honour of his queen after the first landing there in 1583 CE. Queen Elizabeth provided this new expedition with the 160-ton ship Tyger. Grenville left Plymouth on 9 April 1585 CE with his fleet of five ships, of which Tyger was the largest. The crew included a young Thomas Cavendish (1560-1592 CE) who would later circumnavigate the globe in 1586-88 CE. Another famous name was John White (c. 1540 - c. 1593 CE), the celebrated cartographer and artist who mapped and captured the sights of this corner of the New World and who had already accompanied Martin Frobisher in his search for the Northwest Passage in the 1570s CE.

A storm in mid-May separated the fleet, and Grenville in the Tyger was blown off course to end up in Puerto Rico. A few small Spanish vessels and ports were then plundered in the Caribbean - as was always intended - in order to pay for the expedition. Eventually regrouping and restocking at Hispaniola, three ships made their way tentatively through the difficult shallows of the Carolina Banks. In mid-July, the Tyger ran aground and seawater seeped into the ship's stores, ruining much of the foodstuffs meant for the colonists. The trio of ships was then joined by the remaining two vessels which had also got lost in the storm.

The settlers were led by Ralph Lane (d. 1603 CE) and, unable to reach the mainland proper, they were deposited on Wokokan Island. Lane and Grenville did not get on and the colonists moved to nearby Roanoke Island (in modern-day North Carolina) when the mariner sailed back to England for more supplies. Lane was left with the smallest vessel, the pinnace, with which he might explore the region. Grenville, meanwhile, like most Elizabethan mariners, never turned down the chance of a little profit if the opportunity presented itself. Off Bermuda, he captured the 300-ton Santa Maria de San Vicente on his way home. The capture of sugar, ivory, and spices would pay off all of the expedition's costs.

The Azores Expedition & the Revenge

In the summer of 1588 CE, Grenville fought with success in the battles to repel the Spanish Armada with which Philip II of Spain (r. 1556-1598 CE) hoped to conquer England. In 1591 CE England's policy against Spain was to attack their treasure ships laden with gold and silver from the New World. In this way, Philip II would be deprived of the resources needed to build a second Armada and the English crown would get correspondingly richer with the loot taken. The field of operation was chosen as the Azores island group in the mid-Atlantic, and Grenville was appointed second in command of an expedition led by Lord Thomas Howard. Grenville's ship was the Revenge, which had seen sterling service as Drake's flagship in the battles with the Spanish Armada. The English fleet of six royal ships and a number of private warships and supply vessels left Plymouth on 5 April 1591 CE. Several Spanish treasure ships were captured along the way over the next three months. It looked like the Azores would be a happy hunting ground for the privateers.

Things went wrong in the Azores when a large Spanish fleet of 56 ships, including 17 royal galleons and commanded by Don Alonso de Bazán, arrived unexpectedly in August. Howard had been awaiting a treasure fleet due from the west and not this fleet of warships from the east; consequently, he withdrew. Grenville was given the task of forming a rearguard escort to the fleeing English fleet and so was left the most exposed ship. Grenville was delayed after he picked up 90 of the Revenge's crew on land where they had been recuperating after a wave of illness had hit the English fleet. It is also possible that Grenville deliberately tried to engage the enemy in that typical heady cocktail of bravado and folly that Elizabeth's leading mariners seemed unable to abstain from.

In the confusion, the Revenge managed to twice repel a party of Spanish marines who boarded the ship, sink two enemy ships, and inflict damage on 15 others. Grenville was gravely wounded by a musket ball, though, and he gave orders for the Revenge to be scuppered by blowing up the powder store. The crew, almost all of whom were wounded, ignored their now unconscious captain and surrendered. Grenville was taken captive but died from his wounds a few days later. As it happened, the Revenge and seven ships of the Spanish fleet were then sunk by a hurricane.

The heroic last stand of the Revenge was described in detail in Sir Walter Raleigh's Report of the Truth of the Fight about the Isles of Azores and famously became a subject of a poem, The Revenge, by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892 CE). Below is an extract from that poem.

And the night went down, and the sun smiled out far over the summer sea,

And the Spanish fleet with broken sides lay round us all in a ring;

But they dared not touch us again, for they fear'd that we still could sting,

So they watch'd what the end would be.

And we had not fought them in vain,

But in perilous plight were we,

Seeing forty of our poor hundred were slain,

And half of the rest of us maim'd for life

In the crash of the cannonades and the desperate strife;

And the sick men down in the hold were most of them stark and cold,

And the pikes were all broken or bent, and the powder was all of it spent;

And the masts and the rigging were lying over the side;

But Sir Richard cried in his English pride:

“We have fought such a fight for a day and a night

As may never be fought again!

We have won great glory, my men!

And a day less or more

At sea or ashore,

We die - does it matter when?

The last stand of the Revenge became the stuff of legend and remembered as one of the great episodes of the then still-young Royal Navy. For the Spanish, meanwhile, the battle in the Azores displayed the advantages of using a military convoy for their treasure ships and they would employ this strategy with success from then on. Some great galleons loaded with treasure would still be captured but the convoy system now allowed a steady river of gold and silver to safely reach a Spain now at the zenith of its power.