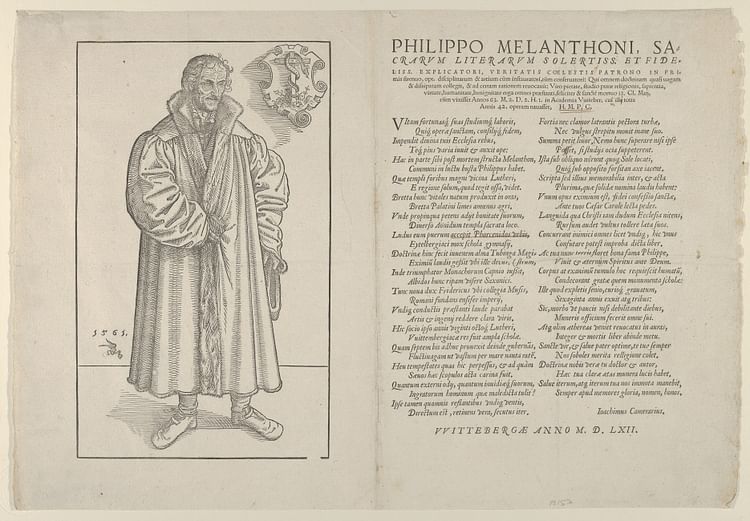

Philip Melanchthon (l. 1497-1560) was a German scholar and theologian who provided the intellectual rationale and systematized theology for the reformed vision of Christianity of his friend Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546). He was always overshadowed by Luther, but the Protestant Reformation would not have developed or succeeded as it did without him.

Melanchthon was the great-nephew of the humanist scholar Johann Reuchlin (l. 1455-1522) who influenced his love of learning and was instrumental in securing Melanchthon's position as Professor of Greek at Wittenberg in 1518. Melanchthon already knew of Luther by reputation, but at Wittenberg, they would become close friends and co-reformers.

Luther developed the theology of the Reformation in Germany, but Melanchthon systematized and clarified it. The most famous examples of this are the Loci communes rerum theologicarum seu hypotyposes theological ("Common Places in Theology") of 1521, outlining fundamental doctrine, and the Augsburg Confession of 1530, which became the confession of faith for Lutherans and the fundamental text of Protestantism.

After Luther died in 1546, Melanchthon became the leader of the Reformation in Germany, though his position was challenged as he was thought to have compromised with the Catholic Church. He continued to write and carry on the work of the Reformation until his death in 1560 from fever. Melanchthon is remembered as the stabilizing force counterbalancing Luther's passionate call for reform and, later, break with the Church. Modern-day Lutheranism is understood by many scholars as owing as much of its theology to him as to its founder.

Early Life & Studies

Melanchthon was born into an affluent family in Bretten, Germany, as Philip Schwartzerdt on 16 February 1497, son of George Schwartzerdt and Barbara Reuter. His father worked as an armorer for Philip the Upright, an Elector (one of the nobles who elected the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, which Germany was part of at this time). His great-uncle, Johann Reuchlin (his mother's uncle), was a leading scholar of ancient Greek and Hebrew, who had fought against the agenda of some clergy to systematically destroy Jewish books and scripture as anti-Christian. Reuchlin won his cause but at great personal expense.

His influence on Melanchthon was considerable not only as a humanist but also for his stand against a policy encouraged by the Church. Although Reuchlin never joined the Reformation, he supported reform and not only served as a role model for his great-nephew but was also responsible for the name he is known by. In keeping with the scholarly practice of the time, Reuchlin had Graecized his name to Capnion in his writings as it was thought a Greek name sounded more impressive. He suggested his great-nephew do the same in pursuing his studies, and so Philip Schwartzerdt ("black earth") became Philip Melanchthon (meaning the same in Greek).

Melanchthon showed great promise as a scholar at an early age and was sent to school for Latin in 1507 when he was ten years old. He also learned Greek and became especially fond of the works of Aristotle. After his father and grandfather died in 1508, he and his brother lived with Reuchlin's sister, Elizabeth, who encouraged his academic pursuits. In 1509, he enrolled at the University of Heidelberg and graduated in 1512 but was denied his master's degree on account of his young age of only 15. He continued his education at Tubingen and was awarded his master's in 1514 (or 1516), in philosophy and rhetoric, at which point he began his study of theology.

No doubt influenced by Reuchlin, Melanchthon did not accept church doctrine or policy unquestioningly and, although still maintaining that Aristotle's works were of value, began to doubt the Church's claim that they were essential for the interpretation of scripture. Luther, meanwhile, had come to this same conclusion. Luther's 97 Theses, arguing against the tradition of Scholastic Theology (using scholastic works, primarily Aristotle, in understanding the nature of God), were posted in 1517, only a month before his more famous 95 Theses.

Although they had not yet met, the two men were in agreement on a number of points, and Melanchthon was already facing opposition at Tubingen as a 'reformer' at a time when this term bordered on being called a heretic. When Reuchlin was offered a position at the University of Wittenberg, he declined but suggested Melanchthon for the posting at the same time Luther wrote Melanchthon inviting him to come. Melanchthon accepted the position of Professor of Greek in 1518 at the age of 21.

Martin Luther's 95 Theses & Reformation

The famous image of Luther nailing his 95 Theses to the door of Castle Church in Wittenberg comes from Melanchthon, but he was not in Wittenberg on 31 October 1517. Further, Luther himself never mentions nailing the theses to the door in any of his letters or writings. The story appears nowhere, in fact, until Melanchthon's 1548 History of the Life and Acts of Luther, published two years after Luther's death. By this time, Luther's reputation was firmly established, and the story of the rebel priest nailing his challenge to a church door fit the narrative.

The story was accepted as fact until 1961 when scholar Erwin Iserloh noted that Melanchthon could not have been an eyewitness to the event since he had not yet arrived in Wittenberg in October 1517 and, as noted, there was no mention of the event until after Luther's death. Still, the historicity of the nailing of the 95 Theses continues to be debated and is more often than not presented as historical fact.

This is not only because the story has been repeated for so long but also because it fits the image Luther himself cultivated of a Christ-like figure offering himself as a martyr to the truth of the Christian vision. The image of the defiant Luther nailing his theses to the Church door is certainly one he himself would have cultivated as evidenced by Luther's speech at the Diet of Worms and earlier. Luther's followers were depicting him in the role of Christ by 1521, before and after his appearance at the Diet of Worms, but he had already cultivated the image by 1518 after his 95 Theses were translated from Latin to German and spread throughout Germany. Scholar Lyndal Roper comments:

Written by an unknown German professor in an intellectual backwater, the Ninety-Five Theses nonetheless gained widespread attention with startling speed. In just two months they were known all over Germany and were already being met with refutations. In Augsburg, the cathedral preacher Urbanus Rhegius remarked that Luther's "disputation note" was available everywhere. (83)

Records indicate that a number of clergy received hand-written copies of the 95 Theses from December 1517 through March 1518, contradicting Luther's claim that only one copy of his disputations had been sent to his archbishop and that he only intended the theses for scholarly debate by local clergy. Evidence suggests that Luther was already presenting himself as God's instrument in reforming the Church at this time. The 95 Theses were so instantly popular and influential, Melanchthon may have felt they required a more dramatic appearance and so created the story. It is also possible, however, that the event is historical, Luther told him the story, and Melanchthon only found the opportunity to use it in his 1548 work on his friend's life.

Whatever the true story of the 95 Theses is, it is certain that Melanchthon was supporting Luther shortly after arriving at Wittenberg in 1518, traveling with him later that year to the examination by Cardinal Cajetan at Augsburg and the debate at Leipzig between Luther and co-reformer Andreas Karlstadt (l. 1486-1541) on one side and the theologian Johann Eck (l. 1486-1543) on the other. Melanchthon was not a participant in the debate but was allowed to comment as a spectator and later defended his points in a tract against Eck.

Marriage & Major Works

In 1520, Melanchthon married Katharina Krapp (also given as Krappe, l. 1497-1557), daughter of Hans Krapp, mayor of Wittenberg, who was an admirer of Luther. Luther, in fact, arranged the marriage because he felt Melanchthon, whom he often refers to as "scrawny" or "small and sickly looking," could not find a wife for himself and needed one to take care of him (Lyndal, 191). The couple would have four children: Anna, Philip, Georg, and Magdalen. Their marriage was a happy one, and Melanchthon encouraged marriages among former Catholic clergy, even though he had reservations about Luther marrying in 1525 as he felt it would damage his image and provide opponents with ammunition they could use against him. Eventually, however, he came to see Luther's marriage to Katharina von Bora as a positive contribution to the cause.

Melanchthon continued his support for Luther in early 1521 through writings but did not accompany him to the Diet of Worms in April. There, Luther delivered his now-famous "Here I Stand" speech, refusing to recant and, afterwards, attempts were made by various members of the examining committee to persuade him in private. One of their more threatening arguments was that, if Luther were condemned as a heretic and outlaw, Melanchthon would be dragged down with him.

Certain of Melanchthon's support, however, Luther did not waver. He left Worms a little over a week after his appearance and was taken into protective custody by his secret patron Frederick III (the Wise, l. 1463-1525) at Wartburg Castle. Luther had been abducted for his own safety, but this had been staged as a kidnapping by highwaymen to protect Frederick III as much as Luther. Luther wrote Melanchthon that he was safe, and at Wartburg, he wrote several important works and translated the New Testament into German, while Melanchthon, back in Wittenberg, was writing his Loci communes. Roper comments:

Melanchthon had embarked on the Loci communes (Commonplaces), his great work of systematization of Reformation theology, which would create a doctrinal corpus for the new movement. Luther's respect for the younger man grew, and as he read Melanchthon's drafts in Wartburg, he would repeatedly state that Melanchthon was the better scholar. (187)

The Loci communes is an in-depth discussion of the major points of Saint Paul's Epistle to the Romans, emphasizing the importance of faith over good works and noting how medieval church policy deviated from scripture. Luther objected to some of his arguments, such as those on monastic vows, claiming that, if vows to the Church should be broken to avoid sin, then marriage vows could also be broken, or any vows at all. Melanchthon modified this passage as he would some others, and Luther's commentaries on his drafts were carefully considered, but the work is really entirely Melanchthon's. The Loci communes became the systematic theology of the Protestant Reformation, not only in Germany but also elsewhere.

The Augsburg Confession of 1530 was equally important. Melanchthon wrote this piece for presentation at the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, which was a conference called by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, to address, among other issues, Christian disunity in Germany. Charles V was concerned over the possibility of an invasion by the Ottoman Empire (another reason for the conference) and wanted the schism caused by the Lutherans resolved so Christians could present a united front against Ottoman aggression.

Melanchthon composed the Augsburg Confession as a statement of faith, not only for Luther's followers but for the whole Church and so tried to compromise on a number of different points both Lutherans and Catholics could agree on. Luther, branded an outlaw after the Diet of Worms in 1521, could not attend the conference and was represented by Melanchthon, but the latter's willingness to compromise created tension between the two. Roper notes:

For Luther, compromise was now out of the question. Letters he wrote just before the end of the Diet reveal just how far relations with Melanchthon had deteriorated. On September 20, Luther told Melanchthon that people had been complaining about his conduct of the negotiations and asked for more detail, "so that I can stop the mouths of your detractors." (329)

Luther admired Melanchthon's scholarship and literary skill in composing the Augsburg Confession and claimed he himself could not have done better, but even so, Melanchthon's willingness to compromise, his use of reason in arguments (instead of appeal to scripture), and his omission of certain criticisms of the Church, encouraged the tension between them. Their arguments afterwards all developed from professional differences on doctrine and how that should best be codified. Both respected the other's stand but disagreed on how they represented the faith. Luther, to Melanchthon, was too prone to angry outbursts which offered no compromise; Melanchthon, to Luther, was too lenient in debate and too willing to concede to avoid conflict.

Despite Melanchthon's best efforts, the disputations at Augsburg failed to reconcile Lutherans with Catholics, as neither side trusted the other, and the Lutherans feared any major compromise would lead to their destruction. Roper comments:

What finally kept the two sides apart was the absence of trust – on marriage, the sacraments, and other issues, the evangelicals simply did not believe that the Catholics meant what they said, or that they would keep their word. (330)

Still, many of the princes present signed the Augsburg Confession, and Melanchthon's attempt at unifying the Catholic and Lutheran visions had come close to succeeding. Luther was not pleased by some of Melanchthon's concessions, but the frequently repeated claim that this caused a rift between the two that was never reconciled is an exaggeration.

Luther & Melanchthon

Luther and Melanchthon continued to respect and defend each other for the rest of their lives, and if there was any rift, it was professional, not personal. Scholar Bengt Hagglund writes:

The tension between Luther and Melanchthon concerned not only doctrinal questions but also the church politics, the way in which they developed, declared, and fought for an evangelical confession. (126)

To this end, Luther sent a number of letters to Melanchthon at Augsburg encouraging him to take a firmer stand on issues. Melanchthon, however, had always tried to diffuse conflict, not encourage it, while Luther regularly pursued the opposite course. Scholar Roland H. Bainton comments:

Luther was exceedingly concerned and wrote to him that the difference between them was that Melanchthon was [resolute] and Luther yielding in personal disputes, but the reverse was true on public controversies…Melanchthon was for recognizing even the pope, whereas Luther felt that there could be no peace with the pope unless he abolished the papacy. The real point was not between personal and public controversies, but in their respective judgments of the left and of the right. Melanchthon, in his efforts to conciliate the Catholics, was in danger of emasculating the Reform. But he did not. The Augsburg Confession was his work, and in the end, it was as stalwart a confession as any. (334)

Melanchthon's works after Augsburg only increased his standing as Luther's right-hand man and a reformer in his own right. While Luther preached and wrote often fiery polemics against his opponents, Melanchthon reasoned with them. Their different approaches have given rise to the concept of Melanchthon as the 'brains' and Luther the 'brawn' of the Reformation, but this is unfair to both men. Melanchthon could argue theology and scripture as well as Luther, and Luther had as firm a grasp of scholarship and rhetoric as Melanchthon, enabling them to establish the foundations of the Protestant Church in Germany, which neither could have accomplished alone.

Conclusion

After Luther's death in 1546, Melanchthon was recognized as the leader of the Reformation, but at the same time, without Luther to defend him, he was criticized for his Augsburg compromises and others in later works. Melanchthon's aversion to conflict and desire for peace encouraged a number of Lutheran clerics to reject his leadership as suspect and in league with the Catholic Church. Melanchthon stood his ground, however, and continued to lead the Reformation, establish the University of Leipzig, organize public education, and establish Protestant policies at Tubingen, Wittenberg, and elsewhere.

Melanchthon continued the work of the Reformation up until his death on 19 April 1560. He is said to have spent his last moments, suffering from a flu and fever, concerned only for the future of the Church with no thought of himself and expressing no fear of death. He, like Luther, died peacefully, associating the two in death as they had been in life. Hagglund comments:

In many respects, the idea that the Reformation was the common work of Luther and Melanchthon corresponds to the facts. There were, in fact, many others who also made very fundamental contributions, so that we rightly call them "reformers" too. But the two outstanding personalities were Luther and Melanchthon. We know that Luther himself appreciated his co-reformer as his most valued colleague, whose skill, learning, and depth of theological insight were of the greatest importance for the entire Reformation. (125)

His body was buried next to Luther's in the cemetery of Castle Church in Wittenberg where, according to Melanchthon's account, Luther had posted his 95 Theses in 1517. Melanchthon is widely recognized today as one of the most important figures of the Protestant Reformation and is especially honored among Lutherans for his contributions to a cause that changed the world.