John Cabot (aka Giovanni Caboto, c. 1450 - c. 1498 CE) was an Italian explorer who famously visited the eastern coast of Canada in 1497 CE and 1498 CE in his ship the Mathew (also spelt Matthew). Sponsored by Henry VII of England (r. 1485-1509 CE) to search for a sea route to Asia, Cabot's expeditions 'discovered' what the Italian called 'Newe Founde Launde'. Cabot was probably, then, the first European since the Vikings to land in and explore North America. Unable to find a passage from that continent to Asia, Cabot either died during his second voyage or returned to England and obscurity c. 1500 CE; the reasons for his demise - one way or another - remain a mystery.

Man of Mystery

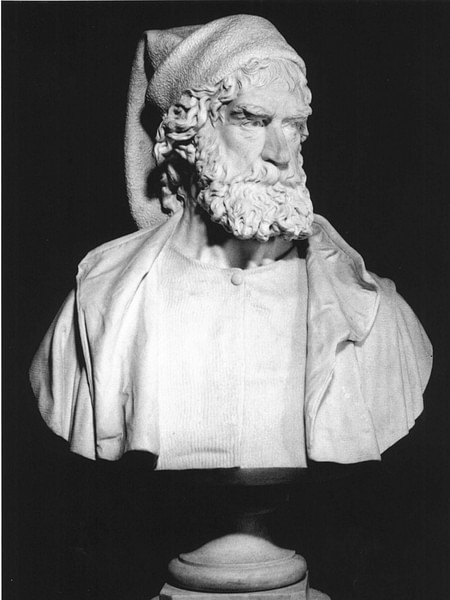

The life of John Cabot is shrouded in layers of mystery and confusion. We do not know the precise date or place of his birth. We do not even know how to spell his name correctly - variations include Chabotto, Gaboto, Caboto, Talbot and, of course, the anglicised Cabot. Even what he himself used as his first name throughout his life is disputed; the possibilities include John, Giovanni, Joanes, Johannes, Juan, Zuan, Zuam, and Zoane (all variations of the same name in different languages). Where exactly he sailed to, where he first landed, and how he died are yet more points of uncertainty. The explorer left no written records, and there are no surviving contemporary portraits of him. Even Cabot's charts and achievements, won by hard toil and experience, were soon lost and forgotten in Tudor times. John Cabot is one of those prime examples that in order to be remembered accurately, one must have the luck to attract a near-contemporary historian and chronicler to record one's life in detail. Cabot had no such good fortune. Fortunately for posterity, besides other scholars past and present, the multinational and collaborative Cabot Project of the Department of History of the University of Bristol has been tireless in its ongoing research into just who John Cabot was and what his achievements were.

Early Life

We do know that Cabot was born in Italy around 1450 CE, and Genoa is most often cited as his hometown. He lived in Venice, worked as a trader and became a citizen of that maritime power in 1476 CE. Cabot stole a march on his merchant rivals, who typically traded eastern goods at Alexandria in Egypt, by travelling in person overland to Mecca and the trading posts established around that city. We know that Cabot married a Venetian called Mathye and had three sons: Ludovico (spelt 'Lewes' in English documents), Sebastian, and Sancio.

Cabot then seems to have got into some financial difficulties and perhaps fled Venice for that reason. Already ambitious to explore across the Atlantic Ocean and in desperate need of wealthy sponsors, Cabot spent some time in Spain in the early 1490s CE, residing at both Valencia and Seville. At the latter city, he was involved in a bridge-building operation which was as unsuccessful as his attempts to find financial backers for his proposed voyage.

Still involved in trade and perhaps in another attempt to cut out unnecessary middlemen, Cabot relocated to England in the mid-1490s CE. Cabot joined the community of Venetians which had taken up permanent residence in Bristol, then England's most bustling port. Bristol, like Venice, was another place rich in maritime history and intrepid fishermen and explorers had already sailed from there to Iceland and Greenland in the search for greater fish catches. Cabot was by now bursting to follow in their wakes and sail even further beyond the western horizon. Like most navigators of the period, Cabot believed that by crossing the North Atlantic he might well find what later became known as the Northwest Passage to Asia and particularly the East Indies with its lucrative exotic goods such as silk and spices. This route would be much shorter and safer than any then-known alternative. Cabot was convinced that Christopher Columbus (1451-1506 CE) had not discovered anything more important than a few minor islands in his voyage of 1492 CE. The fact that a massive continent lay between Europe and Asia was still not known. Cabot believed the best sea route to Asia was much further north than Columbus had explored and so that was where he would sail.

First Voyage to the Americas

Cabot seems to have relocated to London, again living with the Venetian community in that city. He then proposed to Henry VII a voyage to North America and the English king duly granted him a license in 1496 CE. The monarch described the Italian as "our well beloved John Cabot, citizen of Venice" (Hale, 65). The aim was to not only find the Northwest Passage but also to seek out any new lands not already known to Europeans and to establish trade with any indigenous peoples Cabot might come across; Henry would receive a 20% cut of any profits from such trade. Despite this royal support, the expedition was largely financed by an Italian bank in London, presumably with a similar hoped-for profit dividend on completion of the voyage. Merchants from Bristol must also have been involved given the wording of Henry VII's royal patent.

Cabot first set off on 2 May 1496 CE but a series of tremendous gales wrote off the season and eventually drove his ship back to port in Bristol for lack of provisions. Undeterred, Cabot set off again on 20 May 1497 CE in his single ship the Mathew, a 24 metres (78 ft.) long, three-masted caravel. The 50-ton Mathew was not purpose-built for the expedition and had served in maritime trade previously (and would do so again after Cabot's voyage). The caravel class of ships were light, fast, manoeuvrable, and did not require a large crew making it an ideal choice for the purposes of exploration in unfamiliar waters.

Crossing the Atlantic over the next five weeks, he most likely reached what is today Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia on 24 June 1497 CE. Cabot then sailed north, exploring the coastline of what he called 'Newe Founde Launde', which is the origin of today's Newfoundland in eastern Canada. However, the explorer's exact first landfall, subsequent stops and precise coastal route are not known and much disputed amongst historians. Cabot himself thought he had reached the east coast of Asia, probably Japan, then known as Cipango. Wherever he thought he was, this was the first European in North America since the Vikings. The explorer landed on terra firma and had a cross set up to mark the event. He then flew Henry VII's royal banner, and the banners of the Pope and Saint Mark of Venice. There was clear evidence of indigenous peoples living in these parts such as old fires, simple tools, and carvings on trees, but no sight of the people themselves.

It was in these waters that Cabot noted the abundance of cod, a discovery which would soon be exploited by French and English fleets (but was already familiar to Portuguese and Breton fisherman). The explorer then sailed home in quick time thanks to favourable winds, landing back at Bristol on 6 August. News of the great schools of cod was announced first as the returning mariners boasted to their colleagues in the docks that "they would bring thence so many fish that they would have no further need of Iceland" (Williams, 14). Cabot meanwhile reported to Henry VII that he had discovered the extreme west coast of Asia and this seemed a very good candidate for a short route to that continent that might be exploited for trade purposes. The English king was notoriously careful with his funds, and he awarded Cabot, as indicated in the royal archives, the paltry sum of £10 for his achievement (but still about a year's wages for a craftsman at the time). Perhaps feeling a little guilty at his meanness, especially as the foreign ambassadors at court were abuzz with news that England had laid a claim to a new land in North America, Henry later awarded Cabot an annual pension of £20.

Second Voyage to the Americas

Cabot was now able to demonstrate to investors the potential of his discovery and so he organised a second voyage. This one was much more of a commercial venture with a consortium of English merchants putting together a fleet of five ships and filling them with trade goods. The king also got involved again and supplied one of the ships. This time a number of Italian friars came along to act as missionaries, including one Giovanni de Carbonariis. Cabot left Bristol again in 1498 CE, perhaps stopping off at Greenland (although this may be pure legend) and once more reaching Newfoundland, perhaps even exploring as far south as Chesapeake Bay (in Maryland and Virginia, USA) or even the Caribbean.

It was on this second trip that Cabot may have died, but the precise circumstances of his demise are not known, only that he now disappears from history. Some modern researchers, notably one of the foremost experts on John Cabot, Alwyn Ruddock, have suggested that Cabot did return to England c. 1500 CE but then disappeared from the historical record because his second voyage had been a commercial failure and/or his incursion into the Spanish-controlled Caribbean was an embarrassment the English authorities wished to hush up. Records indicate that Cabot's pension was paid in 1498 and 1499 CE, but of course, this may have been paid to his widow. Cabot's end, then, is a mystery, and compounded by a second one: the incomprehensible decision of Ruddock, who had been preparing a book on Cabot for over 20 years, to have all her unpublished research destroyed following her death in 2005 CE.

Legacy

A small-scale private venture was not successful in setting out from Bristol and emulating Cabot and so there followed a long pause in England's overseas exploits which held during the reigns of Henry VII's three Tudor successors. England's claims to territory in the Americas established by Cabot would not be pursued until the reign of Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603 CE), specifically from the 1570s CE onwards. However, the exploring bug that Cabot had let loose would finally bite many new English explorers in the Elizabethan era and beyond. Cabot's voyages particularly stimulated greater interest in trying to find the Northwest Passage, notably the three expeditions of Martin Frobisher (c. 1535-1594 CE) between 1576 and 1578 CE.

Another of John Cabot's legacies was the adventures of his son Sebastian Cabot (1474-1557 CE) who had accompanied his father to the New World. Sebastian went on to explore Newfoundland in 1508-9 CE, and with the support of other Continental European monarchs, the coasts of Brazil and the River Plate between 1526 and 1530 CE. Sebastian Cabot then returned to England and masterminded several trade expeditions to Russia in the 1550s CE.

A full-size replica of John Cabot's Mathew was built in England in 1996 CE to mark the 500th anniversary of the explorer's first voyage. The ship is permanently docked at Bristol harbour but does occasionally make sorties to other ports. Finally, as mentioned above, the Cabot Project at the University of Bristol continues to conduct research into John Cabot's life and voyages, as well as that of Sebastian Cabot and other noted mariners who set sail from Bristol in the 15th and 16th century CE.