The Council of Clermont in central France was held in November 1095 and witnessed Pope Urban II's (r. 1088-1099) historic call for the First Crusade (1095-1102) to capture Jerusalem for Christendom from its Muslim occupiers. The Pope's speech to the church hierarchy and crowd of laymen at Clermont famously promised all participants a remission of their sins.

Urban II’s strategy of absolving Crusaders of their sins proved hugely popular amongst Europe's nobility and knights. Not surprisingly, it was a ploy copied by subsequent popes for all crusades thereafter. The Council of Clermont thus set off a chain of events that would lead to warfare between East and West for the next two centuries and more, a conflict which brought repercussions for all the states involved right down to the present day.

Prologue: Jerusalem & the Seljuks

When the Muslim Seljuks, a Turkish steppe tribe, spectacularly defeated an army of the Byzantine Empire at the Battle of Manzikert in ancient Armenia in August 1071, a series of events followed which would lead to centuries of East-West warfare couched in religious terms: the Crusades. The Seljuks created the Sultanate of Rum and conquered Byzantine Edessa and Antioch in 1078. Next, they captured Jerusalem from their rival Muslims, the Fatimids of Egypt, in 1087 (the city had been in Muslim hands since the 7th century). Alexios I Komnenos, the Byzantine emperor (r. 1081-1118) realised that Seljuk expansion into the Holy Land was a perfect opportunity to gain the help of western armies in his battle to control Asia Minor and so he sent a direct appeal to Pope Urban II in March 1095. Both the Pope and western knights would respond in a far greater capacity than Alexios could ever have imagined.

Pope Urban II

Pope Urban II had been in office since 1088 and had already gained a reputation as a reformer and active promoter of the idea of expanding Christendom by whatever means necessary. Hailing from a noble family from northern France, Urban II would establish himself as one of the most influential popes in history. Earlier popes had not shied away from military action, in 1053 Pope Leo IX (r. 1049-1054) had sent armies to battle the Normans in the south of Italy. Pope Gregory VII (r. 1073-1085) had theorised on the virtues of a Holy War, and Urban himself had already sent troops to help the Byzantines in 1091 against the Pecheneg steppe nomads who were invading the northern Danube area of the empire.

Urban II was again disposed to give military assistance to the Byzantines for various reasons. A crusade to bring the Holy Land back under Christian control was an end in itself - what better way to protect such important sites as the tomb of Jesus Christ, the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Christians living there or visiting on pilgrimage also required protection. In addition, there were very useful additional benefits. A crusade would increase the prestige of the Papacy, as it led a combined western army, and consolidate its position in Italy itself, having experienced serious threats from the Holy Roman Emperors in the previous century which had even forced the popes to relocate away from Rome. Urban II also hoped to make himself head of a united Western (Catholic) and Eastern (Orthodox) Christian church, above the Patriarch of Constantinople. The two churches had been split since 1054 over disagreements about doctrine and liturgical practices. As a suitable platform to announce his plans, Urban II called a council of church elders in November 1095; the location: Clermont in central France.

The Clermont Indulgence

The Council of Clermont of 18-28 November was an impressive gathering of 13 archbishops, 82 bishops, and 90 abbots, chaired by the Pope himself and held in the cathedral of the city. Clearly, something big was about to happen. After nine days of ecclesiastical discussion and debate, 32 canons were issued such as the reaffirmation of the prohibition of clerical marriage, and the authority of the see of Lyons was formally set above that of Sens and Reims. There was, too, the excommunication of both the Bishop of Cambrai and King Philip I of France (r. 1059-1108), the former for selling church privileges and the latter for adultery. All quite run-of-the-mill issues for the medieval Church, but it was canon number 33, the last one to be issued, that would shake the world.

On 27 November the cream of the French clergy and a crowd of laymen gathered in a field just outside Clermont for the finale of the council. It was here that Urban II made his now famous speech in an obviously pre-prepared set piece. The message, known as the Indulgence, was addressed in particular to Christian nobles and knights across Europe. Urban II promised that all those who defended Christendom and captured Jerusalem would be embarking on a pilgrimage, all their sins would be washed away, and their souls would reap untold rewards in the next life. In case anyone was concerned, a group of church scholars later went to work and came up with the idea that a campaign of violence could be justified by references to particular passages of the Bible and the works of Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430). Further justification for war was the emphasis that this was a fight for liberation, not an attack, and that the objectives were just and righteous ones. Urban II had managed to hit a collective nerve in Europe with a powerful idea that weaved together the great themes of the age: religious fervour, deep concern for the afterlife, love of pilgrimage, and thirst for martial adventure amongst the nobility. The same winning combination would be used again and again by Urban's successors to gain wide support for the many subsequent crusades in the next two centuries.

Unfortunately, no contemporary document outlining the precise content of Urban II's Clermont speech exists except the following short summary extract, a decree from the Council:

Whoever for devotion alone, not to gain honour or money, goes to Jerusalem to liberate the Church of God can substitute this journey for all penance' (quoted in Phillips, 18)

There are, though, many medieval secondary sources which refer to the speech and its contents, even if these must be treated with caution as they date to after the conclusion of the Crusade. Several such sources were written by eyewitnesses at Clermont, and by careful comparison and consideration of the writers' original aims in documenting the events, along with surviving letters written by Urban II, certain common features do stand out. The Pope made it very clear that:

- Jerusalem was the primary objective, with the defence of the Byzantine Empire a second aim.

- the suffering of Christians and desecration of holy sites there (albeit exaggerated for effect) made the timing imperative.

- those who fought would be rewarded in this life with material rewards and, in the next life, with spiritual ones.

- the Crusade would necessitate the end of the various damaging wars between Europe's nobles.

- only fit fighting men should answer this call, and their property would be safeguarded in their absence.

Below is an extract from one such account, written c. 1110 by Robert of Rheims:

…A grave report has come from lands around Jerusalem and from the city of Constantinople…that people from the kingdom of the Persians, a foreign race, a race absolutely alien to God…has invaded the land of those Christians, has reduced the people with sword, rapine and flame and has carried off some as captives to its own land, has cut down others by pitiable murder and has either completely razed the churches of God to the ground or enslaved them to the practice of its own rites…On whom, therefore, does the task lie of avenging this, of redeeming the situation, if not on you?

Stop these hatreds among yourselves, silence the quarrels, still the wars and let all dissensions be settled. Take the road to the Holy Sepulchre, rescue that land from a dreadful race and rule over it yourselves, for that land that, as scripture says, floweth with milk and honey was given by God as a possession to the children of Israel.

But we do not order or urge old men or the inform or those least suited to arms to undertake this journey; nor should women go at all without their husbands or brothers or official permission: such people are more of a hinderance than a help, more of a burden than a benefit. (Phillips, 210-11)

In another extract, this one from the account written by Guibert of Nogent sometime prior to 1108, the point is made that the reward of a remission of sins was only previously available to those who adopted a life in a monastery:

God has, in our time, instituted holy warfare in order that arms-bearers…might find a new way of obtaining salvation; so that they might not be obliged to leave the world completely, as used to be the case, by adopting the monastic way of life or any form of professed calling, but might attain some measure of God's grace while enjoying their usual freedom and dress. (Philips, 212)

Finally, in this extract from Baldric of Bourgueil's account (c. 1105) there are words of comfort for those touched by the Pope's pleas and inspired to take up the dangerous challenge of warfare in an unknown and far-off land:

Do not worry about the coming journey: remember that nothing is impossible for those who fear God, nor for those who truly love him…Gird thy sword, each man of you, upon thy thigh, Oh thou most mighty. Gird yourselves, I say, and act like mighty sons, because it is better for you to die in battle than to tolerate the abuse of your race and your Holy Places. (Phillips, 213)

The speech, whatever its precise wording, was met with immediate enthusiasm. Some of the audience followed the reaction of the bishop of Le Puy, Adhémar of Monteil, shouting out 'God wills it!'. The bishop then, as was almost certainly pre-choreographed, came on the stage and received his cross, the symbol of a Crusader's vow, from Urban II. The choice of the cross as the banner of the campaign was a powerful visual reminder not only of the Crucifixion which had, after all, occurred at the Crusade's objective of Jerusalem but also of what would then have been the well-known command from Jesus recorded in the book of Matthew of the New Testament (16:24):

If any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow me.

Much more important than the effect on the immediate audience at Clermont, the Indulgence, once its message was spread, electrified medieval Europe and saw an overwhelming response with thousands 'taking up the cross' and vowing to crusade for Christendom. Indeed, the speech was almost too good, and unheeding the Pope's advice, a rabble of untrained men, led by Peter the Hermit, a self-styled evangelist, was the first group to travel to the Holy Land via Constantinople, the so-called People's Crusades. This group, containing hardly any professional knights was, unsurprisingly, wiped out in Asia Minor in October 1096 by a Seljuk army.

Aftermath

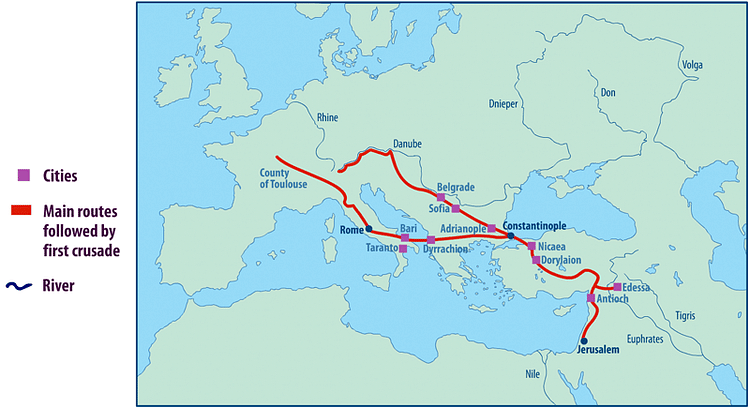

After the council, Urban II wrote many letters of appeal and embarked on a preaching tour of France during 1095-6 to recruit crusaders, where his message was spiced up with exaggerated tales of how, at that very moment, Christian monuments were being defiled and Christian believers persecuted and tortured with impunity. Embassies and letters were dispatched to all parts of Christendom. Major churches such as those at Limoges, Angers, and Tours acted as recruitment centres where the Clermont speech was repeated. Many rural churches and monasteries also gathered up funds and recruits. Across Europe warriors, stirred by notions of religious fervour, personal salvation, pilgrimage, adventure, and a desire for material wealth, gathered throughout 1096, ready to embark for Jerusalem. The departure date was set for 15 August of that year. Around 60,000 crusaders including some 6,000 knights would be involved in the first waves.

The Crusade was a remarkable success. In 1097 Nicaea was captured and a great victory was won at Dorylaion. In June 1098 Antioch was captured after a lengthy siege and a Muslim relief army defeated. Then, the big catch and objective of the campaign, Jerusalem was captured on 15 July 1099. Another Muslim relief army was defeated at Ascalon in August of the same year; Caesarea and Acre were taken in 1101. The Holy Land was finally back in Christian hands, and the Council of Clermont had achieved its purpose, even if Urban II died on 29 July 1099 without knowing its success. The trick now was to keep those gains, a task which, despite vast resources and the support of kings, would, in the end, prove to be too much for the royal houses of Europe.