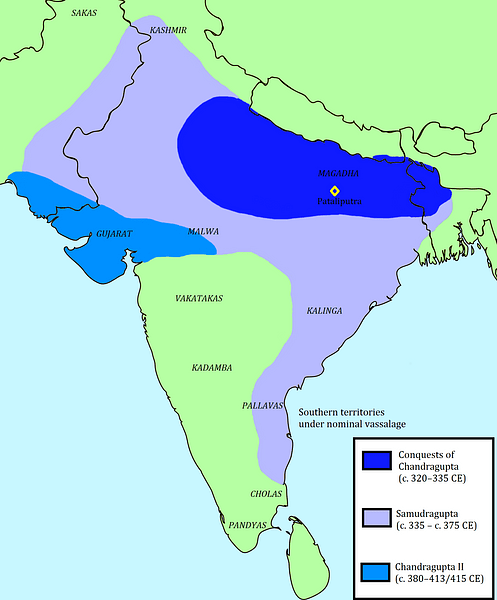

Chandragupta II (c. 375 CE - 413/14 CE) was the next great Gupta emperor after his father Samudragupta (335/350 - 370/380 CE). He proved to be an able ruler and conqueror with many achievements to his credit. He came to be known by his title Vikramaditya (Sanskrit: "Sun of Power"). He carried on the legacy of Samudragupta and contributed his share towards sustaining an extensive empire that carved out a place for itself in history.

Succession

Chandragupta's accession to the throne was not smooth, as he had to depose his brother Ramagupta. Samudragupta had been succeeded by his eldest son Ramagupta (370-375 CE). The existence of coins and inscriptions recording the installation of images in a Jaina temple in central India by Maharajadhiraja (Sanskrit: "Lord of Great Kings") Ramagupta attest to the existence of this king. The Gupta inscriptions do not mention Ramagupta, for the simple reason that going by the tradition of ancient Indian genealogies, deposed kings are hardly mentioned as the focus is on the king who deposed him and his successors. Thus, "since the succession passed to Chandragupta and his sons, Ramagupta is ignored" (Singh, 479).

There is no historical evidence discovered as yet as to how and why Chandragupta followed his brother on the throne. The sole mention of it occurs only in literary sources, with the foremost being the Sanskrit play Devichandraguptam ("Devi and Chandragupta") written by the celebrated playwright Vishakhadatta sometime between the 4th and 8th centuries CE. According to the story in the play, Ramagupta was a weak and immoral king. Unable to face the might of the Shaka (Scythian) king, he agreed to the terms of surrender which included also the surrender of his wife, the Chief Queen Dhruvadevi (Devi or Dhruvasvamini) to the enemy king. His younger brother Chandragupta could not stand this disgrace. Disguising himself as the Queen, he reached the enemy camp and killed the Shaka king in his sleep. Ramagupta was petrified at this incident and greatly feared a heavy Shaka backlash. Disgusted by his brother's cowardice, Chandragupta eventually deposed and killed him. He then married Dhruvadevi and ascended the throne.

Many historians maintain that it is not known as to "how far the story embodies genuine historical tradition" (Majumdar, 141). Nonetheless, the events as stated by the play continued to find reverberations in later literary texts including the Harshacharita or the biography of Emperor Harshavardhana or Harsha (606 – 647 CE) of the Pushyabhuti Dynasty, written by his court poet Banabhatta or Bana (c. 7th century CE). Bana writes, "In his enemy's city the king of the Shakas, while courting another's wife, was butchered by Chandragupta concealed in his mistress's dress" (Banabhatta, 194).

The inscriptions of the Rashtrakuta Dynasty (8th-10th century CE) of southern India also cite these happenings (mentions are made of a Gupta prince who killed his elder brother, and then seized his kingdom, marrying his queen), thus showing that these events or their knowledge was well part of public memory even in the 9th and 10th centuries CE. Historian RK Mookerji says that "the original story mentioned by Bana received additions and embellishments in later texts, literary and epigraphic" (Mookerji, 67). Chandragupta, historically, did have a queen named Dhruvadevi, who was the mother of his successor, Kumaragupta I (414-455 CE). Thus, it is quite probable that Vishakhadatta built up his plot around historical persons, based on what was known (or supposed) of them at his time, which perhaps included recollection of some enduring animosity between the two brothers over the throne, or possibly even over Dhruvadevi.

The historical importance of this play, however, lies in the establishment of the identity of Ramagupta - otherwise so completely dismissed by the official Gupta records - both as an actual person and as the successor of Samudragupta. This has helped historians view any inscriptions or other evidence associated with this name very closely, and try to figure out what had really happened in his reign. Most of the details are yet to be known.

Political Conditions

Samudragupta's exertions had created a vast empire, and so "Chandragupta II was spared the difficult task of building up an empire" (Tripathi, 250). Samudragupta's strategy was guided by the prevailing political and economic conditions. He realized that he could not control directly a vast empire from his capital and hence focused on annexing those kingdoms which lay on his borders. For the rest, only an acceptance of suzerainty would do while their own kings would be left to deal with issues of governance and administration. At the same time, being subordinate, they would not create challenges for the Guptas. Therefore, unlike the Mauryas (4th-2nd century BCE), the Gupta Empire under Samudragupta did not directly control many of its constituents. Samudragupta, thus, despite his conquests, did not create an all-India empire. Using his military power, he instead built up the political machinery in such a way that the Gupta suzerainty and paramountcy came to be acknowledged over most of the subcontinent and many kingdoms and republics regarded themselves as subordinate to the Gupta emperor.

Given the time, with feudalism making rapid inroads, this was probably the best way to create a widespread empire. Direct control and a centralized system as under the Maurya Empire were no longer tenable. In the changed circumstances, the Guptas could not hope to exercise monopolistic control over the economy and hence could not have the vast resources necessary to run a bureaucratic empire with a vast military. The best idea, then, was to build a military mighty enough to cow down the enemy and keep him cowed. Able to garner suzerainty in such a manner, Samudragupta believed he could create and keep the peace necessary for his empire to prosper. At the same time, many of those subordinate dynasties would continue to grow as well but would be left alone as long as they did not challenge the Gupta power.

Chandragupta, in his time, felt the same way. For him, what remained was to either fight the remaining kings that had not been tackled by Samudragupta or to ally himself with the prominent dynasties that had retained their power and were ruling their own lands, and over time, could become strong enough to rival his might. He thus fought wherever possible and settled for peacemaking elsewhere.

Alliances

In keeping with the times, Chandragupta also applied his diplomatic skills to good use. The Guptas were the most prominent dynasty of their time, but there were others who were turning out to be quite powerful themselves. Since warfare was not always the best means to tackle them, often non-military means, particularly matrimonial matchmaking, were adopted to keep these powers in check, subdued, or taken as allies.

Chandragupta took as one of his queens Princess Kuberanaga, thus pacifying the strong Naga Dynasty ruling in parts of north-central India. Another power that needed attention was the Vakataka Dynasty of western India. This kingdom was strategically located, particularly from a campaign perspective, as its "geographical position could affect movements to its north against the Shaka satrapies of Gujarat and Saurashtra" (Mookerjee, 48). Chandragupta settled for a matrimonial alliance with the Vakatakas by marrying his and Kuberanaga's daughter Prabhavatigupta to the Vakataka king Rudrasena II (380-385 CE). Upon the latter's death, Prabhavatigupta became regent for her minor son, and many historians believe that through her Chandragupta extended his rule to the Vakataka kingdom as well, as Prabhavatigupta was ruling according to her father's advice and guidance. The Gupta sway over the kingdom of Kuntala in southern India, for instance, was brought about "by the regency administration of Queen Prabhavatigupta seeking her father's intervention which was further increased under the inefficient rule of her son given to a life of luxury and poetical preoccupation" (Mookerjee, 47).

Conquests & the Shaka Campaign

Chandragupta continued with Samudragupta's expansionist policy and led campaigns into Bengal (eastern India) and Punjab (north-western India). The Shakas of western India (also known as the Western Satrapas) constituted the biggest threat to the Gupta Empire at this time. Chandragupta's war was a protracted one and lasted nearly 20 years, with his coins first appearing in the region in 409 CE.

Though no historical evidence is available as yet in this regard, it is quite probable that Ramagupta may have realized the danger coming from the Shaka quarter, and planned on tackling them. Either the campaign never occurred or it simply fell through, and it was then that Prince Chandragupta chose to take up the initiative, which he did by eventually murdering the Shaka king. Unable to go further, he could have allowed the leaderless and demoralized Shaka troops to disperse and return, and who later probably regrouped under a new king. Ramagupta's deposition, or the conditions of intrigue prevailing in the Gupta court, would have halted a follow-up action, and it was left to Chandragupta as the new emperor to now decide the course of action.

Gupta inscriptions mention Chandragupta's campaign against the Shakas as part of his ambition of world conquest (prithvijaya). The Vakataka alliance proved to be of use as access routes were gained and the emperor, working on improving and augmenting his army with greater numbers, marched on. His victories on the battlefield decided the final outcome, and it is extremely improbable that he killed the enemy king in disguise, as it would have been very degrading for an emperor to do the work of a lowly assassin.

Administration

Chandragupta's empire extended "from Bengal to the north-west and from the Himalayan terai to the Narmada (river)" (Singh, 480). The conquest of western India, particularly what is now the present-day Gujarat state, gave the Guptas direct access to the seaports there. According to the various Gupta-period seals and inscriptions that have been discovered, there was a vast hierarchy of officials with varying ranks and designations. The topmost was the emperor with titles like parameshvara (Sanskrit: "supreme god"). Below him was the uparika (viceroy or governor) directly appointed by the emperor, and who governed the province (desha or bhukti). He had military duties as well and headed the provincial troops. The province was divided into districts (vishaya) headed by a chief (vishayapati) appointed by the uparika. The lowest unit of administration was the village (grama) which chose its own functionaries, including the chief (gramika) and a ruling body consisting of village elders.

The emperor was assisted by a council of ministers (mantrins). An important designation was that of the mahasandhivigrahaka (Minister of Peace and War). Revenue sources consisted chiefly of taxes and tolls, while the state observed monopoly over sources such as mines and salt reserves.

Conditions

Trade flourished during Chandragupta's time and his inscriptions refer to the existence of trade guilds. These belonged variously to bankers (shreshthis), traders and caravan leaders (sarthavahas) and merchants (kulikas). Overseas commerce received a huge boost once the western seaports became part of the Gupta Empire. Sculpture, painting and religious architecture were highly encouraged.

The chief religions at this time were Buddhism and Hinduism. The latter was divided into two main sects of Shaivism and Vaishnavism (centring around the worship of the gods Shiva and Vishnu, respectively). "Apart from the inscriptions, the coins of Chandragupta II indicate his personal religion of Vaishnavism" (Mookerjee, 52). The emperor thus greatly patronized the Vaishnava sect and was known by the title of paramabhagavata (Sanskrit: "foremost among the worshippers of Vishnu"). However, his officials could freely follow their own religions and sects, as many of them made donations to Buddhist shrines and clerical community (sangha) and to Shaiva temples. Religious endowments by nearly all classes of people to whichever faith they belonged to were common in the period.

An iron pillar known as the Mehrauli Pillar, now seen at the Qutb Complex, New Delhi, India, is seen as embodying the zenith reached by Gupta metallurgy. It is composed of pure wrought iron, containing 99.7 percent iron with very low sulfur and very high phosphorus content. Erected during the time of Chandragupta, and thus having an existence of around 1600 years, it is even today comparatively rust-free, with only the underground and topmost portions rusting and that too due to prolonged contact with water.

Army

Chandragupta II was as skilled in Indian warfare as his father. Inscriptions, especially those issued by Prabhavatigupta, describe him as a matchless warrior and as an exterminator of kings. It is thus likely that he devoted much of his attention to the upkeep of his army in good order and ensured that it remained battle-worthy.

Increased contact with the Scythians (Shakas and Kushanas) in India caused many of their military equipment and clothing to be adopted by the Guptas; "it was the Kushana army, well clad and equipped, that became the prototype on which the new military uniform of the Guptas was based" (Alkazi, 99).

The soldiers mostly abandoned the complex turban that had been usually worn earlier and wore their hair loose or tied back with a fillet or skull caps and simple turbans, with tunics, crossed belts on the bare chest or a short, tight-fitting blouse. This was accompanied by a typically Indian, loose lower garment worn in the drawer style or Scythian-inspired trousers with high boots, helmets, and caps.

There was even a kind of camouflage clothing made by applying tie-dye techniques to cloth. The cavalrymen wore coats and trousers, which were often very colourful and gaily decorated. The elephant warriors were dressed in decorated blouses and striped drawers. The elites commanding the army or other officials, along with coats and trousers, wore armour (especially of metal). Other classes of crack troops were similarly well-furnished.

Shields were rectangular or curved and often made from rhinoceros hide in checked designs. Many kinds of weapons such as curved swords, bows and arrows, javelins, lances, axes, pikes, clubs and maces were used.

In ancient India, initially, the army was fourfold (chaturanga), consisting of infantry, cavalry, elephants and chariots. By the time of the Guptas, the chariots were going into disuse, and the onus was falling on the other three arms. Each arm had its own head (or commander). The chief of the army was called the baladhikarananika or baladhikarana. The head of the infantry and the cavalry was the bhatashvapati. The head of the elephants was known as the mahapilupati. The army consisted of the standing army of the state (maula), mercenaries (bhrita), allied forces (mitra), and those furnished by corporate guilds (shreni).

Legacy

Chandragupta II created a large measure of stability in his time. Kumaragupta I's reign was thus largely peaceful. The achievements in various facets of life, particularly economic and in the realm of art, contributed to further progress in the later periods, and have left behind an enduring legacy.