Zarathustra (also given as Zoroaster, Zartosht, Zarathustra Spitama, l. c. 1500-1000 BCE) was the Persian priest-turned-prophet who founded the religion of Zoroastrianism (also given as Mazdayasna “devotion to Mazda”), the first monotheistic religion in the world, whose precepts would come to influence later faiths.

He was a priest of the Early Iranian Religion who received a vision from Ahura Mazda – the chief deity of that faith's pantheon – telling him to correct the error of polytheistic religious understanding and proclaim the existence of only one true god – Ahura Mazda – the Lord of Wisdom.

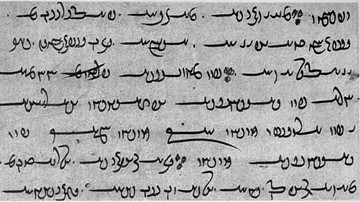

Zarathustra initially met with harsh resistance to his message until he converted the king Vishtaspa, who then led his people to the new faith. Zarathustra then received messages from Ahura Mazda while he was deep in prayerful meditation which he would repeat to his disciples. These messages came in answer to questions and were memorized by the prophet and his followers as a living scripture which was passed down from generation to generation in the ancient language known as Avestan. The faith was embraced by the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) and the Parthian Empire (247 BCE-224 CE) who maintained the oral tradition. Under the Parthian Empire, a written record of the conversations between Zarathustra and his God was initiated.

The scriptures were finally committed to writing by the scribes of the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) after Zoroastrianism was declared the state religion. The oral tradition in written form became known as the Avesta (also given as Zend Avesta). Zarathustra's vision of a single, all-powerful, all-good God who took a personal interest in the lives and particularly the morality of human beings would inform the later monotheistic faiths of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Early Life & Religion

There is no scholarly consensus on when Zarathustra lived or even the meaning of his name. It is generally understood that in the old Iranian language some variant such as Zara-ustra had something to do with the care of camels which may point to his family's occupation, though this is far from clear. The dates of c. 1500-1000 BCE are commonly accepted for the time in which he lived, taught, and founded his religion based on a long tradition of scholarly work on the timeline of the Early Iranian Religion, evidence of the acceptance of Zoroastrianism, and references in the Avesta.

His place of birth and lineage are also unknown. The Avesta, the only source of information on Zarathustra outside of commentaries written on it and legends, does not concern itself with the details of the prophet's life nor with the peoples he would have interacted with such as the Medes or Persians. Once Zoroastrianism had been accepted, many different peoples of various regions claimed Zarathustra as their own and provided justification for those claims but none are any more convincing than another.

He is thought, however, to have been born to Persian parents based on their names, Pourusaspa and Dughdova. His family name was Spitama (meaning, roughly, “of a white or shining power”). His father, Pourusaspa, was probably a priest and his son would become one as sons usually followed in their fathers' professions. He had four brothers (two older and two younger) and was educated at an early age, suggesting a family of significant means in that he was not sent to work nor is there any suggestion of his having any occupation other than priest.

The faith he was devoted to is referenced today as the Early Iranian Religion or the Ancient Persian Religion and was a polytheistic belief system in which many gods were presided over by a chief deity, Ahura Mazda, who guided human activity through benevolence and wisdom, keeping at bay the dark forces of the evil spirit Angra Mainyu (later known as Ahriman). Ahura Mazda had his gods and spirits of light and Angra Mainyu his own legions of demons and spirits of darkness and the two were in constant conflict over control of the world. Every good gift which Ahura Mazda bestowed on the world would be corrupted by the schemes of Angra Mainyu who, nevertheless, would be thwarted by Ahura Mazda's wisdom in bringing good even from evil intentions.

Caught between these two entities were human beings and the early faith, as far as can be understood from later reconstructions, emphasized the primacy of free will in choosing which side one would ally one's self with. One could choose the path of light and love by submitting to the will of Ahura Mazda and one would then live well on earth and be assured of an afterlife in paradise or one could join in rebellion and mischief with Angra Mainyu, corrupt whatever was good for one's own selfish delights, and spend one's life vainly attempting to find happiness in the misery of others and, finally, pass on to a dark hell after death. Whichever path one chose, it was entirely one's own responsibility as Ahura Mazda had granted humans the power of choice and there was nothing more potent than human free will as not even Ahura Mazda could (or would) try to subvert it.

Conversion & Mission

The Early Iranian Religion kept an oral tradition and so, with no written scripture nor commentary, there is no way of knowing how the faith's rituals were conducted. It is known, from references in the Avesta and other Zoroastrian works, that there was a priestly class (the magi) and worship services were conducted outdoors at shrines known as Fire Temples. Sacrifices were made at these temples, most likely in the form of grains, animals, precious metals, and objects, which became the property of the priests. In time, the priestly class grew wealthy from these sacrifices and their probable control of rich farmlands. The names of two types of priests are given as karpans and kawis, but the distinction between them is unclear as are their roles in religious observance.

At the age of 30, he attended the festival of the Rites of Spring (almost certainly the Nowruz Festival celebrating the New Year) and was saying prayers by a river when he experienced a divine vision. On the riverbank before him, a celestial entity appeared in bright light calling himself Vohu Mahah (“good purpose”) and telling Zarathustra that he had been sent by Ahura Mazda himself to deliver a message of vital importance: the religion of the people as it was being practiced was in error. There were not many gods requiring different types of sacrifice but only one god, Ahura Mazda, who was not interested in animal sacrifice but in moral behavior. Vohu Mahah told Zarathustra that he had been chosen by the One True God to preach this news and bring the people to proper understanding of their relationship with the Divine.

Zarathustra accepted this vision as legitimate and began his mission instantly. He was rejected by his former colleagues in the priesthood who had no interest in seeing their status challenged by an upstart priest claiming a personal vision from God. His life was threatened, even his family seems to have abandoned him, and he was forced to flee his home. In the Avesta, Zarathustra describes this time in a lament:

What land should I flee to?

Where should I go to flee?

From my family and from my clan

They banish me.

The community to which

I belong has not satisfied me

Nor have [the rulers] of the country.

How, Thee, can I satisfy, O Mazda Ahura? (Yasna 46.1)

Later, in the same chapter, he gives the answer of the god who sends him to preach his vision in the land of the king Vishtaspa; the monarch who would change his life and help establish his religion.

Vishtaspa & Acceptance

Vishtaspa may have been a Bactrian king or may not have existed at all as he is represented. As Zarathustra traveled toward his kingdom, he was in continual prayer with Ahura Mazda, asking questions and receiving guidance, and these conversations would later be included in the Avesta.

Upon arriving at Vishtaspa's court, he was announced and proclaimed his vision. Vishtaspa was no more pleased at hearing of a new faith than the people of Zarathustra's hometown had been and had him engage in a theological debate with the court priests. Zarathustra ably defeated all of their arguments, showing how they worshipped false gods while the One True God was making himself known to them, but this challenged the status quo far too much for Vishtaspa who had Zarathustra imprisoned.

The prophet would not renounce his vision, however, and received wisdom from his god on how to convince Vishtaspa. He miraculously healed the king's favorite horse, which had been suffering from paralysis, and this inclined the king to listen to Zarathustra's message again in private. Vishtaspa was converted and decreed Zarathustra's new faith the religion of the land. According to some traditions, the priests who had argued against Zarathustra were executed.

The new religion seems to have gained more converts fairly quickly and Zarathustra was honored with a place at Vishtaspa's court. He lived there in the company of the king for the rest of his life while establishing the precepts of the faith and proper observance of rituals which, notably, did not include animal sacrifice. He is said to have married three times and to have had three sons and three daughters. According to one tradition, he died of natural causes when he was 77 while, according to another, he was assassinated by a karpan priest in retaliation for dismantling the old religion.

Zoroastrianism

The new faith Zarathustra founded drew on the old but established significant differences. It was based on five principles:

- There is only one God who reigns supreme: Ahura Mazda

- Ahura Mazda is all-good

- His eternal opponent, Angra Mainyu, is all-evil

- Goodness is made apparent through good thoughts, good words, and good deeds

- Each individual has free will to choose between good and evil

Human free will was central to the faith in that one's choice determined one's destiny. In choosing to submit to, and follow, the precepts of Ahura Mazda, one was placing the common good above one's own selfish desires in an effort to maintain the divine order. If one chose to align one's self with Angra Mainyu, one placed one's own interests above those of others which inevitably would characterize one's life as contentious, confused, bitter, envious, and petty. One could live a meaningful, elevated life in service to others and one's God, which would benefit one in this life and the next, or withdraw to the darkness of Angra Mainyu and essentially work against the forces of order and goodness. If one chose the path of Ahura Mazda, one expressed that choice through the central precepts of Good Thoughts, Good Words, Good Deeds and practiced these through:

- Telling the truth at all times – especially keeping promises

- Practicing charity to all – especially the less fortunate

- Showing love for others – even if they did not return that love

- Practicing moderation in all things – especially in one's diet

Virtuous behavior was a reflection of one's faith in an all-good and all-powerful God who cared for humanity and, specifically, had an interest in one's moral and ethical choices. Individual choice defined an individual's life. If one paid lip-service to the faith but acted in opposition to it, one was obviously aligned with Angra Mainyu and the forces of darkness and chaos. If one were truly an adherent of the path of Ahura Mazda, one would show this choice clearly in the three core values of personal behavior:

- To make friends of enemies

- To make the wicked righteous

- To make the ignorant learned

If one chose the path of Ahura Mazda, and regularly showed one's faith through the practice of these precepts, one would lead a life which benefited others as well as one's self. Through consideration of the greater good, one would be expressing the will of the Divine, not just one's personal desires or narrow goals, and would embody the values of the Supreme God in one's daily life. The faithful Zoroastrian would not only live a good and productive life but be assured of paradise after death.

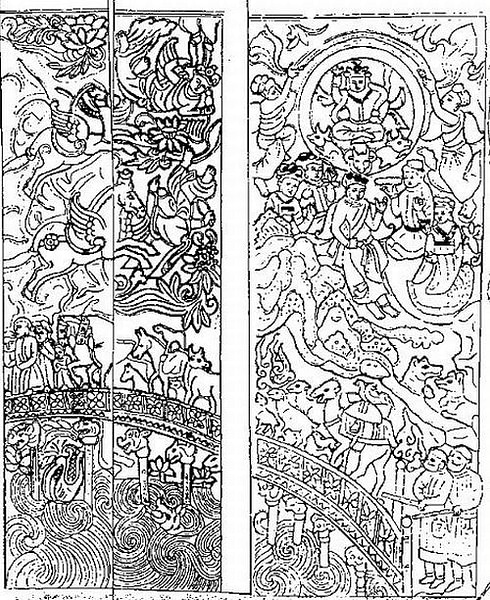

These dogs would welcome a justified soul who had lived well but would snarl at those who had chosen Angra Mainyu's side in the cosmic struggle. After meeting with the dogs, the soul would then encounter the Holy Maiden, Daena, representing the conscience of the deceased. To the blessed soul who would be justified by their choices, Daena would appear as a beautiful young girl; to those who would be condemned in the afterlife for their selfishness, she would seem an ugly old hag.

Daena would lead the soul onto the Chinvat Bridge where it would be protected against demonic attack by the angel Suroosh. As the soul crossed in Suroosh's company, the bridge would widen to welcome the justified soul, making for an easy passage, but would narrow and become precarious for the condemned. Suroosh would guide the soul to the far end where the angel Rashnu, righteous judge of the dead (and, in some traditions, the god Mithra) would decide one's destination.

Those souls whose deeds were more or less equally good and bad went to a kind of purgatory known as Hamistakan where they would remain until the end of earthly time. Those who had lived in accordance with Ahura Mazda's precepts went to the House of Song while those who had chosen Angra Mainyu dropped from the bridge into the House of Lies. There were four levels of paradise ascending upwards from the bridge, each more beautiful than the last, and four levels of hell descending downwards to the lowest which was a pit of absolute darkness where the soul would always feel alone no matter how many others were in its company.

Even so, the state of the soul was not eternal – whether one found paradise or hell waiting – because Ultimate Goodness would not allow any of its creations to suffer eternally nor come to languish in a paradise which required no effort to enjoy. Eventually, a messiah known as the Saoshyant (“One Who Brings Benefit”) would come and bring the Frashokereti (End of Time) when all souls would be reunited with Ahura Mazda in bliss and Angra Mainyu and his demons would be destroyed.

Conclusion

This religion, as noted, was practiced from before the time of the Achaemenid Empire through that of the Sassanians. During that time, innovations were made as evidenced by the so-called “heresy” of Zorvanism which sought to resolve the problem of evil by making a minor god of time, Zorvan, of the Early Iranian Religion, the Supreme Deity. Zorvan, in this belief system, represented Infinite Time and gave birth to the twins Ormuzd (Ahura Mazda) and Ahriman (Angra Mainyu). Ahriman was given control of the world for 9,000 years but Ormuzd would then triumph and destroy the evil works of Ahriman to redeem all the people.

Zarathustra's religion continued to develop until 651 CE when the Muslim Arabs invaded and toppled the Sassanian Empire. The faith had come under attack earlier by zealous Christians in the 4th century CE but they did not have the political power to do much more than harass Zoroastrian clergy and adherents. The Muslim Arabs destroyed Zoroastrian shrines, fire temples, and libraries, burning scores of Persian works, in an effort to subjugate the people and impose their religion.

The Avesta, and commentaries, were saved by the Parsees – those who fled the region for India – or by those who remained and kept the texts hidden. Zarathustra's vision was thereby saved and the practice of his religion continues up through the present day. His concepts of the primacy of free will, individual responsibility for one's choices in life and destination in the afterlife, personal judgment after death, a messiah who redeems the world, a heaven and hell, as well as a bridge between the living and the dead, would come to inform Judaism, Christianity, and Islam significantly. Zarathustra's origins, family, even the meaning of his name might remain obscure but his vision continues to be lived, not only by modern-day adherents of his religion but by the many others whose faiths he lay the foundations for.