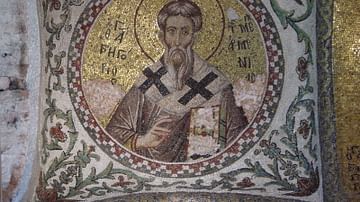

One of the most influential and important Christian leaders during the Early Medieval Period was Pope Gregory the Great (540–604 CE). Renown for his administrative prowess and ecclesiastical reforms during a time of "obscurantism, superstition, and credulity" (Gonzalez, 288), he helped solidify the Christian church as a pillar of European society for centuries to follow. As Moorhead notes, "He is generally regarded as one of the outstanding figures in the long line of popes, and by the late 9th century had come to be known as 'the Great,' a title which is still applied to him." (1)

Pastoral Care

One of Pope Gregory's most famous literary works is the treatise, Pastoral Care (also known in Latin as Liber Regulae Pastoralis), a four-book exposition that offers quintessential guidelines for priests and bishops on how to wisely and biblically lead their churches and how to morally manage their lives. In this writing, Gregory presents his papal opinion on the qualifications, attitudes, choices, and activities of being a good pastor, or, as he terms it, "physicians of the heart." (Book I, Ch. 2.)

For Gregory, the office of pastor existed for the benefit of his flock, not the reverse, which he saw happening far too often in medieval society. MacCulloch remarks,

Gregory the former monk saw that this active ministry in the world might afford clergy the chance to make greater spiritual progress than in a monastery, precisely because it was so difficult to maintain contemplative serenity and an ability to expound good news amid the messiness of everyday life. (328-329)

Gregory begins Pastoral Care by pointing out, "Wherefore, let fear temper the desire; but afterwards, authority being assumed by one who sought it not, let his life commend it." (Book I, introduction) The medieval church pastor position was extremely influential; by word or by deed, a pastor could cause spiritual and physical harm to a parishioner (or even lead them to their death), intentionally or unintentionally. Thus, a contemplative, beneficial attitude of servant leadership had to be maintained. Much like the care and concern a physician has in dealing with the health and wellness of his or her patient, in Gregory's mind, the pastor must be protective and preservative in his treatment of his church flock.

Balance in leadership & trust

Furthermore, even though supposedly a holy physician, a careless pastor might "foul the [same] water," (Book I, Ch. 2.) instead of offering a clear spiritual or biblical solution to the problem besetting the hurting church member. Without proper education and training, the ignorant or worldly pastor could become a stumbling block of destruction rather than the good shepherd leading the sinner to the Good News. Gregory encouraged his readers to find the healthy balance between leadership authority and leadership egomania, being neither too lenient nor too harsh with the suffering parishioner. He writes,

For care should be taken that a ruler show himself to his subjects as a mother in loving-kindness, and as a father in discipline. And all the time it should be seen to with anxious circumspection, that neither discipline be rigid nor loving-kindness lax. (Book II, Ch. 6.)

Trust was another important factor for Gregory concerning pastors and their church, especially considering the number of people dependent upon him. Gregory states,

[A pastor should be] pure in thought, exemplary in conduct, discreet in keeping silence, profitable in speech, in sympathy a near neighbor to everyone, in contemplation exalted above all others, a humble companion to those who lead good lives, erect for his zeal for righteousness against the vices of sinners. (Book II, Ch. 1.)

The pastor should be above reproach so that no obstacles block the approach of his parishioners. People should be eager and willing to receive advice and assistance from their faithful pastor. Moreover, he must perform key pastoral duties and not become arrogant with power and self-righteousness. He writes,

The ruler should be, through humility, a companion of good livers, and, through the zeal of righteousness, rigid against the vices of evil-doers; so that in nothing he prefer himself to the good, and yet, when the fault of the bad requires it, he be at once conscious of the power of his priority; to the end that, while among his subordinates who live well he waives his rank and accounts them as his equals, he may not fear to execute the laws of rectitude towards the perverse. (Book II, Ch. 6.)

Time and time again in Pastoral Care, Gregory expands upon the dangers of over-emphasizing clerical authority and ego, pointing to it as both dangerous and a perversion of human reality. Gregory states,

But since often, when preaching is abundantly poured forth in fitting ways, the mind of the speaker is elevated in itself by a hidden delight in self-display, great care is needed that he may gnaw himself with the laceration of fear, lest he who recalls the diseases of others to health by remedies should himself swell through neglect of his own health; lest in helping others he desert himself, lest in lifting up others he fall. (Book IV)

Self-awareness

Beneath the clerical robes and priestly authority, the pastor was still filled with the same sinful nature as his parishioners. This demanded great self–awareness and internal evaluation so that the pastor's deeds were performed out of genuine love of neighbor rather than the pastor's love of self. Gregory admonishes,

That they should first shake themselves up by lofty deeds, and then make others solicitous for good living; that they should first smite themselves with the wings of their thoughts; that whatsoever in themselves is unprofitably torpid they should discover by anxious investigation, and correct by strict animadversion, and then at length set in order the life of others by speaking; that they should take heed to punish their own faults by bewailings, and then denounce what calls for punishment in others; and that, before they give voice to words of exhortation, they should proclaim in their deeds all that they are about to speak. (Book III, Ch. 40.)

As he understood ministry, a pastoral calling was given to help deliver sinners from their vices, not to dominate or exploit or condemn them, the common worldly abuses of his age. Hiestand and Wilson advocate for this very same concept when they write, "As a pastor, [one] should consider everything in light of the needs of your church." (121) Thus, Gregory's personal papal challenge to all Christian leaders was that they should continuously examine their own lives, personal vices, and failings before criticizing the lives and behaviors of others in their ministerial positions.

Ultimately, it was Gregory's hope that in contemplating and applying the truths of Pastoral Care, pastors would "rejoice not to be over men, but to do them good. For indeed our ancient fathers are said to have been not kings of men, but shepherds of flocks." (Book II, Ch. 6.)