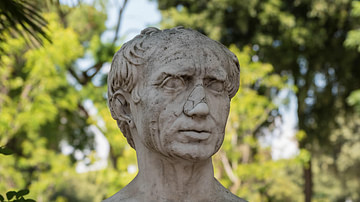

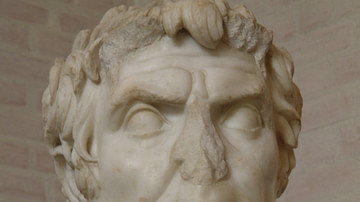

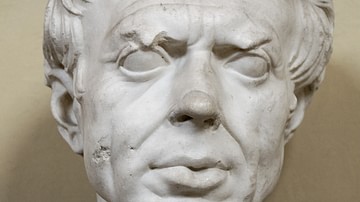

King Mithridates VI of Pontus, also known as Mithradates VI Eupator Dionysus and Mithridates the Great (135–63 BCE, r. 120-63 BCE) was a dogged Roman foe for much of his life. In 88 BCE, he orchestrated the mass killing of up to 150,000 Roman and Italian noncombatants in a single day, if the number of victims Plutarch gave is to be believed, and over the course of decades, he was embroiled in intermittent, bitter conflicts with the Roman Republic. Mithridates' relentless attempts at empire building and his pugnacious foreign policy ensured his place in the annals of history, but his rampant paranoia and obsession with toxicology also guaranteed that his name would forever be associated with poison.

Mithridate

For most of his life, Mithridates understandably worried that he was the target of homicidal plots. Given that royal court intrigues were relatively commonplace in the ancient East, his concerns were probably well founded. Consequently, as Mithridates grew older, he sought to fortify himself against assassination attempts. He exercised to increase his strength, carried a weapon, and dabbled with toxicology. According to legend, Mithridates studiously researched and examined all known toxins and experimented with potential remedies by using prisoners as his guinea pigs. Supposedly, Mithridates' toils paid off because numerous ancient authors, including Pliny the Elder, claimed that he created and regularly ingested a universal antidote for all identified toxins, and it became known as mithridate (mithridatium).

Ancients and moderns alike have diligently attempted to discover Mithridates' panacea, and in fact, purported versions of the Pontic monarch's elixir have existed for thousands of years. But was Mithridates' theriac real, and if so, what were the ingredients? According to Pliny the Elder, the concoction was an amalgamation of over 50 different additives, and allegedly, all of the ingredients were ground into powder, mixed with honey, and formed into almond-sized chewable tablets. However, many of the elements probably acted differently. It has been theorized that Mithridates may have cleverly included miniscule amounts of arsenic, venoms, and other poisons to immunize his body to the deadly toxins. It is possible that he also added additional components to render other poisons impotent, but unfortunately, the original recipe now appears to be hopelessly lost.

Myth or reality?

While many have sought to unearth Mithridates' cure-all potion, few have actually taken the time to doubt the veracity of Mithridates and the ancient authors' assertions. What if Mithridates' panacea was an elaborate ruse meant to persuade his enemies that all poisoning attempts were futile? Mithridates did not conceal his love for toxicology nor did he try to suppress the purported fact that he was in possession of mithridate. He supposedly even publicly ingested fatal doses of poison to prove his invention's efficacy. What a great way to demonstrate to his enemies that he was impervious to toxins! But was he actually consuming poison or a similar looking benign substance? Moderns may never know with certainty, but it seems incredibly likely that he was not hazardously sprinkling lethal doses of poison on his food.

If Mithridates really did possess a panacea, then the wise king would have prudently kept that knowledge a guarded secret. First of all, many others would wish to steal the recipe from him, and considering that Mithridates had a propensity towards poisoning his foes, he would have had good reason to hide his theriac from his adversaries. Secondly, by keeping the concoction a secret, he could find out who his foes were after their failed attempts to assassinate him using toxins. However, instead of keeping the mithridate's existence confidential, it became widely known, which ostensibly halted many of his enemies' assassination attempts. This was probably part of the shrewd king's plans all along. What is the next best thing to having a cure-all antitoxin? Publicly lying about having a cure-all antitoxin to make poisoning attempts seem pointless.

It seems that Mithridates' personal theriac must have either been inadequate or a hoax because he always kept a fatal helping of poison in his sword's hilt in case he decided to kill himself. If he was immune to all toxins, then why did he carry a suicidal dose? Perhaps it was the only poison without a cure. Maybe his panacea only worked if he took it on a daily basis, or quite possibly, the universal antidote was a complete sham.

There are still other deficiencies in the Mithridatium myth. In order to build immunity against certain poisons, it has been asserted that Mithridates consumed small amounts of arsenic and possibly venoms, which may have been included in his chewable tablets, and while this could work in theory, the results would probably have been disastrous. Without modern expertise in dosing, Mithridates would have likely killed himself eventually. If he did not die from accidently consuming a lethal dose, then the effect on his body after years of ingesting toxins would have been severe. Mithridates enjoyed partaking in eating and drinking contests. In fact, he boasted that he could outdrink anyone in his kingdom, which would have left the monarch who lived into his seventies with debilitating liver damage. The combination of a lifetime of binge drinking and consuming toxins would have left his organs in tatters. If he really did drink to a great extent and repeatedly poison himself, then he likely would not have reached the ancient world's ripe old age of seventy-one.

Death by a blade

Those who believe that Mithridates did discover an effective, comprehensive antitoxin claim that the king's botched suicide is proof. In 63 BC, as it became clear that his life was doomed, he attempted suicide by ingesting poison, but he failed to die as a result. It is likely that he only possessed one dose, and he shared the single helping with his two daughters. Yes, the princesses died, and he only became ill. However, it should be noted that he was a large and powerfully built man, and his daughters were likely much smaller, which could explain why the leftover poison was not enough to smite Mithridates. At least a full dose would have been required for a man of his size.

Nevertheless, Mithridates did die but with the help of a blade, and his adherents cared for his corpse and even embalmed it. However, when Pompey the Great arrived to inspect the body, Mithridates' face had decomposed to such a degree that he was unrecognizable. Supposedly, his attendants didn't remove the brain, which allegedly caused the decay, but if Mithridates had spent much of his life consuming small amounts of arsenic, which is a potent preservative, then would his body really have decomposed so quickly? It seems unlikely.

Even though it is doubtful that the Pontic King ever invented an effective and universal panacea, that does not mean that he did not try or even take certain precautions against poisonings. Mithridates was clearly fascinated by toxicology, but the field of study was primitive at the time. There were undoubtedly some known cures for certain ancient toxins, and the intelligent king may have even discovered a few remedies himself. He probably combined and consumed these meager antidotes in Pontus' version of a multi-vitamin, but it likely was not very effective nor was it comprehensive, which the monarch surely understood. However, this would have left someone as paranoid as Mithridates wholly unsatisfied. He probably continued funding research in a desperate attempt to find a universal cure while bragging that he already had obtained it to ward off any attempts on his life. Considering that he was never assassinated by poison, his ploy seems to have been successful.