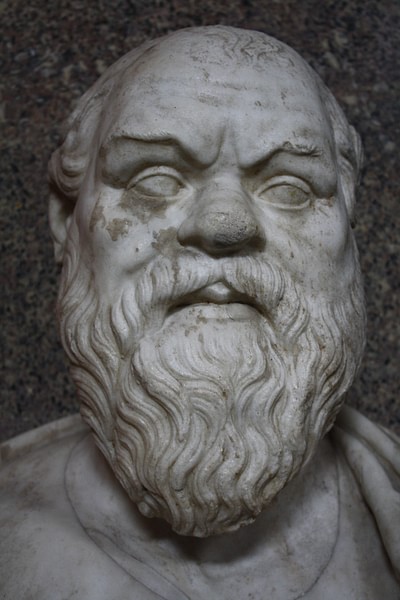

Plato (l. c. 424/423 to 348/347 BCE), the Greek philosopher whose works have significantly shaped Western thought and religion, is said to have initially been a poet and playwright and, even if the primary source of this claim (the often unreliable Diogenes Laertius, l. 3rd century) is challenged, Plato's works themselves argue in favor of it.

Laertius not only claims Plato was originally a poet but that he wrote and taught under a nickname. Laertius claims his real name was Aristocles which means "the best glory" (from the ancient Greek aristos – "best" – and kleos – "glory"), though this claim is challenged by scholar Robin Waterfield (who also places Plato's birth date at 424/423 BCE). Plato's Dialogues reveal almost nothing of his life, and biographical information comes from some letters attributed to him and later writers such as Laertius who, while often considered unreliable, is thought to have worked from more dependable sources (which he never cites) now lost.

According to Laertius, Plato's father, Ariston, traced his descent from the great mythological hero Cadmus, founder of Thebes, slayer of monsters, and so-called "inventor of letters" for bringing the Phoenician alphabet to Greece, while his mother, Perictione, was descended from the family of the great Athenian politician, philosopher, and lawgiver Solon (l. c. 640 to c. 560 BCE). Plato had two older brothers, Adeimantus and Glaucon, and one older sister, Potone, and was provided with the best education available at that time.

The concept of education in ancient Greece was defined by improvements to one's mind and body, and a student needed to prove himself fit in both. Young Plato was taught gymnastics by the wrestler Ariston of Athens, learned equestrian and martial arts, was instructed in music and mathematics by Metallus of Agrigentum and Draco, son of Damon the Sophist, learned to paint and draw, and was introduced to philosophy by Cratylus the Heraclitan (student of Heraclitus of Ephesus, l. c. 500 BCE).

Names in Ancient Greece

In ancient Greece, a child was given a personal name, the name of the father, and a designation of place or tribe to establish identity. Children were almost always given the name of the grandparent; the grandfather if a boy and the grandmother if a girl. The remembrance of the dead was a sacred duty to the Greeks in that, by remembering those who had passed on, the living kept the departed alive and allowed for their participation in the better planes of the afterlife.

The child who would grow up to be known as Plato was born either in Athens or on the nearby island of Aegina. His parents are said to have been among the early Athenian colonists of Aegina and allegedly lived in the house of Phidiades, son of the philosopher Thales of Miletus, before moving back to Athens to the deme (borough) of Colytus. It is possible, therefore, that Plato was born in a house associated with the first known philosopher of ancient Greece, though it is likely this is a later invention. Wherever he was born, according to Laertius, he was named Aristocles, son of Ariston, of Colytus.

Waterfield, however, notes that the name of Plato's grandfather, Aristocles, would have been given to Ariston's eldest son, not his youngest, and that "Plato" was a common Athenian name. It is probable, therefore, that Laertius confused his source material and the future philosopher's birth name was Plato. Laertius describes how "Aristocles" acquired his famous nickname:

Plato learnt gymnastic exercises under the wrestler Ariston of Argos. And it was by him that he had the name of Plato given to him instead of his original name, on account of his robust figure, as he had previously been called Aristocles, after the name of his grandfather, as Alexander informs us in his Successions. But some say that he derived this name from the breadth (platutês) of his eloquence, or else because he was very wide (platus) across the forehead, as Neanthes affirms. (Lives and Opinions, Book III.V)

If Laertius had thought to clearly cite his sources, passages like this would carry more weight with modern-day scholars but, as it is, his work continues to be cited in the absence of other biographical information on Plato and other philosophers of ancient Greece. Waterfield dismisses this passage as "irrelevant" in that it cannot be corroborated and there is no need to question whether "Plato" was Plato's birth name.

As noted, Waterfield also challenges the traditional birth date assigned to Plato of 428/427 BCE:

There are several factors that point to a birth date later than 428/7. The most important is that there is no evidence that he fought in any of the last battles of the Peloponnesian War in 406 and 405, so he was probably still under the age of twenty. Athens was critically short of manpower at the time, so he would certainly have been called up. (Plato of Athens, 3)

Other passages of Laertius' work are regarded as accurate, however, such as his report that Plato was a promising athlete and, as a member of the aristocratic elite of Athens, would have been groomed for a career in politics.

Plato the Poet-Philosopher

At some point in his early 20s, however, the young noble instead gravitated toward the arts. He is said to have written lyric poetry and tragic dramas and seems to have also devoted himself to singing and painting. His plays apparently were good enough to be submitted for consideration for a prize at the Theater of Bacchus, although this claim, like almost all personal information about Plato, cannot be corroborated.

Aristotle (l. 384-322 BCE), Plato's most famous student, provides almost no biographical information on him and most of the letters attributed to Plato which have survived are considered later forgeries written to confirm his reputation as a philosopher. Diogenes Laertius, who provides the most comprehensive account of Plato's life, wrote centuries after his death and, as noted, is often criticized for unsubstantiated claims.

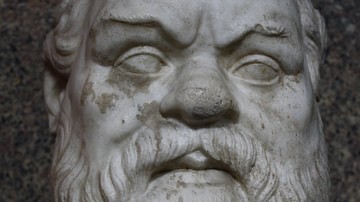

It seems, however, that an encounter in the marketplace of Athens one day would change young Plato's life and, in so doing, change the course of western philosophy and culture. When he was around 20 years old, he heard Socrates teaching in the Agora (the city's outdoor market). He understood, it is said, that what Socrates was teaching was more noble a pursuit than the arts he was presently engaged in, and summoning the god of the hearth, he burned all of his plays and poems and became Socrates' student.

This account is given dramatically by Laertius as a turning point in the young man's life, but he also mentions one of Plato's plays – The Rival Lovers – which he claims was still performed during his time. Further, fragments from dramatists contemporaneous with Plato seem to refer to him as one of their own, such as Anaxandrides of Colophon, who, in a fragment from his play Theseus, calls Plato "worthy" in the sense that Plato was working in Anaxandrides' same art.

It is possible, as some writers have suggested, that Plato burned his early work because he felt it did not meet his standards. This claim, hinted at by Diogenes Laertius, presents the young Plato as an ambitious writer who hoped to be as great as Hesiod or Homer and, failing, set fire to his early literary efforts. It seems certain, whatever the reason behind the destruction of his works, he found in philosophy a more worthy subject than whatever had occupied him previously. For the next few years, Plato would be the student of Socrates until the latter was executed by the Athenians in 399 BCE on the capital charge of impiety.

Travels & Return

After Socrates' death, Plato and many (if not all) of Socrates' former students left Athens to either attach themselves to or establish other philosophical schools and, more importantly, spare themselves the possibility of being charged with similar crimes for association with their master. Plato is said to have gone to Megara, Italy, and other sites of famous philosophical institutes before traveling to Egypt. During this time, he is thought to have studied in schools established by Pythagoras, Euclid, Heraclitus, and others before devoting himself to the religion and metaphysics of Egypt.

Upon returning to Athens, he founded his Academy which taught geometry as a means of clearing the mind (a Pythagorean concept), the Socratic Method of determining truth, and the philosophical-metaphysical understanding of the nature of reality (his Theory of Forms) as expressed in Plato's famous Allegory of the Cave from Book VII of his Republic. This curriculum of the Academy is suggested by fragments from later writers and that of his nephew and successor Speusippus (son of Plato's sister Potone, l. 408-339 BCE) who rejected Plato's Theory of Forms and idealism for a more practical approach to philosophy. At some point after Plato's return, he began writing the dialogues that would establish his reputation.

Plato's Dialogues

That the artist within the philosopher did not die out with the burning of his early works can be easily seen in reading Plato's famous Dialogues. Each of the dialogues is a carefully crafted piece of drama with a sharp focus, rising action, subtle characterization, and dramatic conclusion. His main character is almost always Socrates, who challenges some accepted form of knowledge and forces the other characters – and the reader – to question what they have accepted from others as truth.

Whether Socrates actually behaved as Plato depicts him is unclear as the only other contemporary to write on Socrates was another of his pupils, Xenophon (l. 430 to c. 354 BCE) whose Symposium, Apology, and Memorabilia all deal with his former teacher. Xenophon's Apology is markedly different from Plato's dialogue of the same title in that it is far less literary and dramatic. Xenophon presents the facts of events as he remembers them; Plato presents each event as a teaching moment to explore some aspect of received knowledge.

Plato's Apology depicts Socrates as the heroic philosopher taking a stand for his beliefs against the ignorance and prejudice of accepted religious tradition and custom. Socrates is charged by three prominent Athenian citizens – Meletus, Anytus, and Lycon – with impiety and corrupting the youth through his refusal to acknowledge the gods of Greece and encouraging young men to question their elders. Socrates denies these charges, refuses to recant his beliefs, and defends his pursuit of truth in one of the most famous passages of western philosophical literature:

Men of Athens, I honor and love you; but I shall obey God rather than you and, while I have life and strength, I shall never cease from the practice and teaching of philosophy, exhorting anyone whom I meet after my manner, and convincing him saying: O my friend, why do you who are a citizen of the great and mighty and wise city of Athens care so much about laying up the greatest amount of money and honor and reputation and so little about wisdom and truth and the greatest improvement of the soul, which you never regard or heed at all? Are you not Ashamed of this? And if the person with whom I am arguing says: Yes, but I do care; I do not depart or let him go at once; I interrogate and examine and cross-examine him, and if I think that he has no virtue, but only says that he has, I reproach him with undervaluing the greater, and overvaluing the less. And this I should say to everyone whom I meet, young and old, citizen and alien, but especially to the citizens, inasmuch as they are my brethren. For this is the command of God, as I would have you know: and I believe that to this day no greater good has ever happened in the state than my service to the God. For I do nothing but go about persuading you all, old and young alike, not to take thought for your persons and your properties, but first and chiefly to care about the greatest improvement of the soul. I tell you that virtue is not given by money, but that from virtue come money and every other good of man, public as well as private. This is my teaching, and if this is the doctrine which corrupts the youth, my influence is ruinous indeed. But if anyone says that this is not my teaching, he is speaking an untruth. Wherefore, O men of Athens, I say to you, do as Anytus bids or not as Anytus bids, and either acquit me or not; but whatever you do, know that I shall never alter my ways, not even if I have to die many times.

(29d-30c)

Xenophon's Apology has no such speech, focusing instead on Socrates' belief that his life as lived in public was defense enough, and presents an unadorned version of the trial and aftermath. Plato's account is fuller and far more dramatic with a well-defined hero and equally clear villains. It is also of note that the type of court in which Socrates was tried was only empowered to hear capital cases of murder and clear-cut cases of impiety, such as when one was charged with desecrating a temple or statue or clearly advocating atheism.

Socrates ably demonstrates that he is not guilty of impiety (in both Plato's and Xenophon's accounts) by virtue of the 'voice' he hears from the gods, which directs him to do as he does, and his regular attendance at religious festivals. The more serious charge is that of corrupting the youth through the practice of dialectic, and yet this was not a capital offense in Athens in 399 BCE. Plato's Apology, therefore, must be considered unhistorical and largely a literary work.

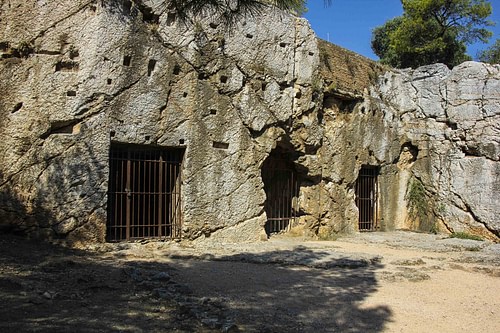

The dialogues dealing with the charges against Socrates, his trial, imprisonment, and execution – the Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, and Phaedo (often published in the modern day under the title The Last Days of Socrates) – all follow this same paradigm of literary constructs reimagining actual events. As a highly educated writer, Plato relies heavily on a reader's understanding of allusion to Greek mythology, characters, and situations and, equally, on the reader having a sense of humor.

Plato's Euthyphro, though a serious inquiry into the nature of the Greek concept of eusebia (piety) can be read as a character study of a young man boasting of knowledge he cannot possibly have in trying to impress an elder. The character of Euthyphro consistently makes outlandish claims to knowledge he cannot possibly possess in an effort to not only justify a lawsuit he is bringing against his father but also show off his intelligence to the older Socrates. The piece is a comic masterpiece in miniature as the increasingly frustrated Socrates tries to get a straight answer out of the clueless young Euthyphro who finally flees the conversation claiming he is pressed for time.

The Crito, a study on the laws of the state and a citizen's obligation to them, takes place in Socrates' prison cell with only Socrates and his old friend Crito present, and even if one accepts the claim that perhaps Crito related their conversation to Plato, the narrative form suggests a literary creation. The same is true of the Phaedo – Plato's grand defense of the immortality of the soul – in which he writes that he was not present at Socrates' death and creates a fictional character of one of Socrates' other students – Phaedo – to narrate the event. The actual, historical Phaedo is said to have charged Plato with making most of his dialogues up and putting his own words into the mouth of Socrates. Socrates, then, would be Plato's most famous fictional character.

Plato's Republic and Laws consider the ideal state as well as, allegorically, the proper ordering of one's soul while other works such as Phaedrus and Ion discuss literary quality, composition, and truth. Plato's famous Symposium focuses on the true nature of love, while his Meno examines what it means to learn and whether virtue can be taught. In all of these – and many others - the philosopher-hero Socrates battles against the forces of entrenched, accepted knowledge to encourage others in the dialogue – and this includes the reader who listens in – to question what they think they know, what they have been taught, and pursue wisdom on their own with a clear mind and dedicated purpose.

Conclusion

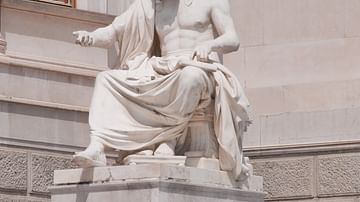

Plato wrote 35 dialogues and 13 letters before he died, and these works contributed enormously to the formation of Western philosophy, culture, and religion, with Plato's emphasis on the immortality of the soul and a realm of objective truth which had to be acknowledged in order to live well. The great 20th-century philosopher Alfred North Whitehead considered all Western philosophy little more than footnotes to Plato as his works have influenced everyone who came after him.

This influence is most apparent in Plato's most famous dialogue, Republic. Professor Forrest E. Baird writes, "There are few books in Western civilization that have had the impact of Plato's Republic - aside from the Bible, perhaps none" (68). This is due not only to the concepts Plato relates in Republic but how he constructs the dialogue to engage a reader in the conversations and arguments of the characters. The narrative form Plato manipulates in Books I-X of Republic takes a reader through the organization of an ideal, just society which is allegorically the most perfect state of an individual soul.

Beginning with a discussion of justice in Book I, Republic ends with an illustration of that concept through the tale of the warrior Er (Ur) who dies, witnesses the truth of the afterlife, and returns to tell others of the importance of justice in Book X; in between, the details of the just life are carefully detailed, disputed, and clarified. The work reads like a drama, with the same conflict, rising action, and dénouement one experiences in Shakespeare, Shaw, Pinter, or Stoppard.

Concepts related to the state of the soul, the nature of a good life, the meaning of quality and justice, and the honest pursuit of truth are further developed, in the same artistic fashion, in Plato's other works. Young Plato may have burned his earlier plays and poems in favor of philosophical pursuits, and perhaps they really were just juvenile efforts he did not want preserved, but his artistic talent is evident in his later works which, literally, transformed the world he left behind.