Transatlantic Zeppelins carried passengers in relative luxury between Germany and New York or Rio de Janeiro during the 1920s and 1930s. The airships Graf Zeppelin and Hindenburg crossed the Atlantic in two or three days, faster than contemporary ocean liners, but this brief golden era of air travel came to an abrupt and tragic end following the Hindenburg disaster in May 1937, when the airship burst into flames and 36 people were killed.

Rigid Airships

While airplanes managed to cross the Atlantic several times in the late 1920s, that particular mode of transport was far from ready to carry paying passengers. The only option to make such a journey by air in the interwar years was in airships, frequently called 'Zeppelins' even if not all were built by the Zeppelin company. Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin (1838-1917) had pioneered rigid airships capable of carrying passengers between various German cities in the first decade of the 20th century. Other nations also tried to master the air with gas-filled ships. The American Walter Wellman, for example, made the first attempt to cross the Atlantic in his airship America in October 1909, but that trip ended in failure.

The German Zeppelins had a rigid metal frame of duralumin, giant hydrogen-filled gas cells, and water tanks for ballast. The skin envelope was usually made of cotton. Engines and crew were housed in gondolas suspended underneath the airship. Zeppelins were fragile and easily damaged in collisions, strong winds made them very difficult to navigate, and the hydrogen they were filled with was highly flammable. As a consequence of these defects, there were many setbacks and disasters, but persistence paid off, and Zeppelins became both a viable form of transport and a potentially lethal weapon of war.

The Zeppelin bombing raids of WWI (1914-18) hit enemy cities in Continental Europe and Great Britain. Although not strategically very effective, these raids led to further innovations in airship design. Britain developed its own airships in response to the Zeppelin threat, but Germany maintained the technological lead. Intercontinental trips became a reality when Zeppelin L 59 flew from Bulgaria to Sudan in November 1917.

The First Atlantic Crossing

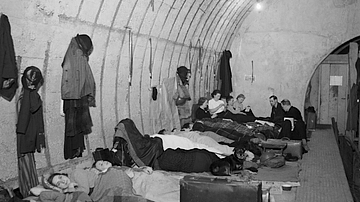

After WWI, airships continued to interest designers and the public alike. The airship R34, built by William Beardmore & Company (and based on a Zeppelin design), flew with a crew of 30 from East Fortune in Scotland to New York. The crossing took 108 hours, from 2 to 6 July 1919. Getting across the ocean safely had been the priority, and comforts were sacrificed, with crew members only provided with hammocks to sleep in. The achievement was reward enough, as was the unique experience, as here described by one crew member: "We feel in a world of our own up here amidst this dazzling array of snow-white clouds. No words can express the wonder, the grandeur, or the loneliness of it all…" (Christopher, 48). The R34 made the return journey back home a few days later, this time taking just 75 hours thanks to more favourable eastward winds. The R34's trip excited the press and public alike and resulted in front-page headlines and even the printing of souvenir postcards. Newspapers and magazines began to print illustrated articles, which dreamed of a brand new way to travel. Airplanes, particularly the flying boats, were getting faster and more reliable, but they remained small affairs incapable of carrying many passengers. The future seemed to belong to the airships. The transatlantic liners of the day could now be challenged by airships capable of crossing the Atlantic faster and without the perils of seasickness.

Return of the Zeppelins

Meanwhile, in Germany, the Treaty of Versailles, which had formally concluded WWI, prohibited the construction of large airships. However, the victorious Allies were reluctant to let German expertise in the field go to waste, and the United States, in particular, pushed for Germany to build a brand new airship capable of transatlantic travel. The resulting airship, LZ 126 (called the Amerikaschiff by the Germans), was built at the Zeppelin headquarters in Friedrichshafen and then given to the United States by way of war reparations. LZ 126 was bigger than any WWI airship, and, powered by five 400 hp engines, it made its first flight on 27 August 1924. The airship had train-like seating inside its gondola, which could be converted to make bunks. The airship was manned by a crew of 28. After more test flights, the LZ 126 was flown from Lake Constance (Bodensee) to New York via the Azores in October and was there received by its new owners, the US Navy. The airship had reached speeds of over 105 mph (170 km/h) and proven, like L 59 and R 34 before it, that airships could safely carry passengers between continents. As LZ 126 flew over Manhattan and circled the Statue of Liberty, once again, the media and public's interest in air travel was rekindled. LZ 126 was renamed the ZR3 Los Angeles by its new owners, and the airship, filled with safer but very rare helium gas, was largely used for research purposes. Other, bigger ships would soon be flying the skies on both sides of the Atlantic.

Graf Zeppelin

The restrictions on airship size German companies could build was finally lifted in 1926. Zeppelin, working in partnership with the US Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, could now, at last, build new giants capable of taking passengers anywhere in the world. The first of these new leviathans was the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin, which crossed the Atlantic in October 1928, where it received a rapturous welcome and a ticker-tape parade.

Graf Zeppelin measured 775 feet (237 m) in length, had a diameter of 100 feet (30.5 m), and a gas volume of 3.7 million cubic feet (105,000 m³). Power came from five 550 hp engines, which used gas for fuel. It had a top speed of 80 mph (128 km/h). The gondola suspended beneath the airship could carry 20 passengers and measured 98.5 feet (30 m) in length and 20 feet (6 m) in width. It had the control room forward and included a map room, radio room, galley, lounge-dining area, sleeping cabins, and washrooms.

As Zeppelin's Dr Hugo Ekener (1868-1954) promised: "You don't fly in an airship, you go voyaging". Certainly, Zeppelin-Goodyear sought to provide its passengers with a comfortable travelling experience. Passengers had their own double cabins and well-appointed public rooms where they could admire the views through panoramic windows and eat food freshly cooked on board. Space was at a premium, and each passenger was only permitted to bring on board 50 lb (22.7 kg) of luggage.

Lady Drummond Hay, a journalist working for Universal News, travelled on the inaugural transatlantic flight of the Graf Zeppelin in 1929. She described her experience as follows:

Those who had not travelled on the Zeppelin before could not tear themselves away from the windows, running from one side to the other, exclaiming at every new phase of the scenery. Others were fascinated by the cabin arrangement, the charming little sleeping compartments…There is a luxurious silk-covered settee which at night is converted into two sleeping berths. Two suede cushion covers disguise the pillows. Wardrobe ample for the journey, a rack for hats, pouches for shoes etc…We passed over a symphony of silver to golden glory as the lights of New York City scattered themselves beneath us like golden stardust, tracing patterns strange and fantastic, set with the jewelled brilliancy of ruby, emerald and topaz electric signs.

(Christopher, 7 & 91)

A Zeppelin crossing of the Atlantic usually took 2-3 days (two days quicker than the fastest ocean liner), but in 1929, the Graf Zeppelin embarked on an even more ambitious route, nothing less than a circumnavigation of the globe. Setting off from New York, the airship's stopovers included Friedrichshafen, Tokyo, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. The airship covered some 19,500 miles (31,400 km). In 1930, the Graf Zeppelin crossed the Atlantic and reached Rio de Janeiro. The world's most famous airship then returned to regularly crossing from Germany to New York but also made trips to Buenos Aires in Argentina and even the Arctic in its long career. Meanwhile, a new leviathan Zeppelin was already under construction, for now called LZ 129.

R 100 & R 101

Britain had been busy building giant airships to provide a regular passenger service between key points of the British Empire, such as London, Montreal, Karachi, Cape Town, and Perth. R 100 and R101, launched in 1929, each had a slimmer profile than the Zeppelins and incorporated their passenger areas within the hull rather than below it. Both R airships were bigger and faster than their German rivals. R 100 flew from Cardington in England to Montreal in Canada in July 1930 and then successfully made the return journey in a record 58 hours. R 101 set off for India in October 1930, but, undertested and suffering weight problems, it crashlanded in Beauvais, France. 48 men died in the crash, which ignited the airship's hydrogen gas. The British government's dream of a global Imperial Airship Scheme also died in the disaster, which had claimed the lives of Britain's top engineering talent.

Hindenburg

Meanwhile, Zeppelin continued to dominate commercial air travel across the Atlantic. The new LZ 129 was designed to be the biggest and most comfortable airship yet built. Constructed at Friedrichshafen from 1931 to 1935, it became the property of a new company, the Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei (DZR), which had involvement from the airline Lufthansa and funding from the German state (which was controlled by the Nazi Party from 1933). LZ 129 made its maiden flight on 4 March 1936. The new name Hindenburg, in honour of the late president of Germany, Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934), was soon emblazoned on the side of the hull in large red Gothic script. Hindenburg's first Atlantic crossing began on 31 March 1936, flying from Friedrichshafen to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The first flight to New York was made in May and took just 61.5 hours. The Hindenburg would make nine more flights to New York and six more to Rio before the year was out.

Almost as long as RMS Titanic and three times longer than a Boeing 747 airplane, the Hindenburg measured a massive 804 feet (245 m) in length with a maximum internal frame diameter of 135 feet (41.2 m). 16 gas cells with a combined capacity of 7 million cubic feet provided lift, and four Daimler-Benz engines provided 3,600 hp to give a top speed of 68 mph (110 km/h). The captain controlled the airship from a gondola beneath the vessel, but passengers were accommodated within a two-deck structure built within the hull. There was room for 50 passengers inside 25 double-berth cabins. Besides the bunk beds, each cabin was equipped with a folding sink that provided both hot and cold water. There was a stool and a fold-down table, but no window. Ten more cabins were added later, including a four-berth one, and so the total passenger capacity was raised to 72.

Either side of the central block of cabins were public areas, which included spacious and comfortable lounge and dining areas with massive windows that sloped significantly outwards to maximise the view. There was a writing room with a small library, a shower room, and a pressurised smoking room with an air-lock door for safety (to keep out any stray hydrogen gas). One could also receive a drink in the smoking room, including the LZ 129 Frosted Cocktail: gin with a splash of orange juice. Furniture was in the modern minimalist style, while the walls were decorated with murals of the history of flight and postal services, and, in the lounge area, a large illuminated map of the world showing the Zeppelin routes. There was central heating, four toilets, and a room of urinals. The crew of 40 worked, slept, and ate four meals a day on the deck below.

With a one-way, all-inclusive ticket costing $400 (the price of a car at the time but still cheaper than a first-class ticket on the best ocean liners), passengers carried with them limited luggage (66 lb or 30 kg), but weighty expectations of an unforgettable flying experience. Every detail, from fine Zeppelin-branded china crockery to the silverware, fresh flowers, and art deco light fixtures, was considered to give a distinct air of luxury. Passengers could even leave their shoes outside their cabins at night and find them freshly polished in the morning. Another service was a special post with letters franked "via the Hindenburg". There was fine cuisine (trout, venison, vintage wines, and champagne), and entertainment was provided by a baby grand piano, specially built from lightweight duralumin. Passengers, who came on board via a stairway beneath the airship, received a helpful booklet, Airship Flights Made Easy, which reassured them of the comforts available but also reminded them not to throw things out of the windows, not to use matches or lighters outside the smoking room, and not to leave the public areas without supervision from a crew member (guided tours within the hull were possible). In short, the brochure promised to fulfil its title:

At the beginning, it is hard to realize you are on board a Zeppelin; the comfort and protection from the weather, the spaciousness, the elegance and neat equipment of the well-appointed cabins, the courtesy and deference of the ship's company who are only too ready to help, awake in you a new conception of pleasurable travel.

(Christopher, 122)

Passengers marvelled at how quiet the engines were and how smooth the trip was. There were cases of passengers not even noticing the airship had left the ground. A common game was to stand a pen on a table and see how long it took to fall. Indeed, the helmsman was under strict orders never to exceed a 5-degree tilt since this might cause wine bottles to fall over in the dining room. The journalist Louis Lochner noted in his diary: "You feel as though you were carried in the arms of angels" (Archbold, 162).

Hindenburg made 17 return trips across the Atlantic in its first season, carrying a total of 1,600 passengers. Despite the high operating costs, Hindenburg almost broke even in its debut year. Carrying mail and small but valuable cargo and participating in air shows were lucrative sidelines for the owners. The Nazi Party was keen to use the Hindenburg for propaganda purposes, and the airship, emblazoned with swastikas on its tail fins, dropped thousands of pro-Nazi leaflets over many different cities during a national referendum, flew over Berlin at the opening ceremony of the 1936 Olympic Games, and made a spectacular appearance at the Nuremberg Rally that year. The Hindenburg and Graf Zeppelin, operating from a new base in Frankfurt, were such a success that construction of another Zeppelin was begun in 1936, the LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II.

Disaster

In 1937, travel by airship seemed to have a long future, but the public's passion for the Zeppelins was about to be extinguished by a terrible disaster. The Hindenburg set off for New York on 3 May 1937 carrying 36 passengers and a crew of 61, larger than usual because there were several trainees who were scheduled to serve on Graf Zeppelin II. The airship faced strong headwinds as it arrived at the Lakehurst landing ground on the evening of 6 May. A few minutes after the landing crew had grabbed the Hindenburg's trailing ground lines a glow and then a small flame was spotted at the top rear of the Zeppelin's hull. Within seconds, the fire spread as the hydrogen gas ignited. The airship dropped towards the ground as the fire raged forward. In just 32 seconds, the airship was incinerated into a pile of twisted metal. 35 people on board (13 passengers and 22 crew) and one member of the ground crew died in the disaster. 62 people survived. The cause of the fire remains a mystery.

The fact that the Hindenburg disaster was caught on film and shown worldwide in newsreels effectively ended air travel using hydrogen-filled airships. The Graf Zeppelin had made 16 round trips to Brazil in 1936 and many more shorter trips in Europe, but the airship was retired in July 1937. Graf Zeppelin II made 30 flights, but none were across the Atlantic and most were inside Germany. Graf Zeppelin II was meant to be filled with safer helium gas, but the US government refused to supply it to Germany over fears the airship might be used for military purposes as war loomed in Europe. Indeed, the Nazi Air Ministry did employ the Zeppelin as an observer of enemy radar systems in 1939. Graf Zeppelin and Graf Zeppelin II were dismantled in 1940, and their massive sheds blown up with dynamite on 6 May, three years to the day after the Hindenburg disaster. Remaining parts of the great Zeppelins, memorabilia of the period, and a full-scale reconstruction of the Hindenburg's passenger lounge can today be seen at the Zeppelin Museum in Friedrichshafen.

The Second World War (1939-45) brought tremendous technical developments to airplanes, although the US Navy did use helium-filled non-rigid airships, the 'Navy blimps', throughout the conflict, mostly for observation purposes. After the war, and despite some plans to build transatlantic passenger airships by Goodyear, the jet engine ensured airplanes and not lighter-than-air airships would dominate the skies thereafter.