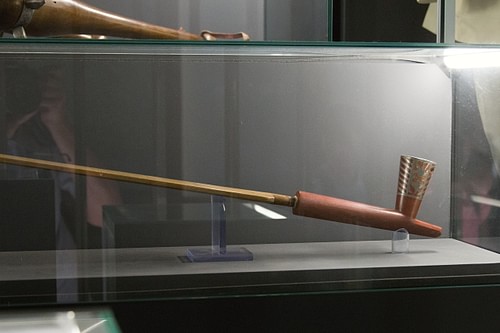

The Sioux ceremonial pipe is a sacred object of the Sioux nation used in the seven sacred rites as well as other observances to connect the people with the Great Spirit (Wakan Tanka), Mother Earth, the spirit world, and each other. Pipe rituals among the Sioux and other nations are dated to at least 3,000 years ago.

The Native American ceremonial pipe is known to non-native peoples as the 'peace pipe' because European colonists and later white Americans most often encountered it when signing treaties with Native nations. The Sioux know the pipe as chanunpa, and, according to their lore, it was given to them by White Buffalo Calf Woman, a spiritual entity, to reestablish the connection between the people and the Creator at a time when this had been lost. White Buffalo Calf Woman also gave the people the seven sacred rites, which inform their spiritual beliefs and during which the chanunpa is to be used:

- Keeping of the Soul (Keeping and Releasing of the Soul)

- The Purification Rite

- Crying for a Vision

- The Sun Dance

- The Making of Relatives

- The Girl's Coming of Age

- The Throwing of the Ball

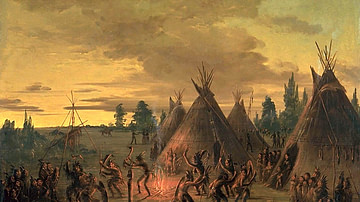

The chanunpa was also used in war councils, to ratify agreements and treaties, and in any observance in which participants sought the wisdom and insight of the Higher Power known as Wakan Tanka (Great Mystery or Great Spirit), the Four Winds, Mother Earth, and the spirits of one's ancestors. The tobacco used in the pipe was considered sacred, was only used ritually, and was not inhaled. By taking the smoke of the pipe into one's mouth and releasing it, one was thought to be sending one's prayers to the world of the spirits; the smoke, honored through the observance of ritual, carried not only one's conscious prayers but also those one might not even be aware of.

The Sioux ceremonial pipe's bowl was often made of catlinite, a soft stone dug from the Pipestone Quarries in modern-day Minnesota, which was attached to a stem of wood decorated with symbolically resonant beads and feathers. Although individuals could, and still do, carry their own chanunpa, the ceremonial pipe given to the people by White Buffalo Calf Woman has been passed down from generation to generation and carefully preserved by a person chosen specifically for this purpose. Presently, the Lakota Sioux spiritual leader Arvol Looking Horse (b. 1954) is the 19th keeper of the sacred pipe.

Origin Stories of the Pipe

The best-known story of the origin of the pipe is given in Myths and Legends of the Sioux by Marie L. McLaughlin (published 1916), who was one-fourth Sioux and lived on Sioux reservations for 40 years, collecting and preserving the people's stories. Her version of the tale is given, with some differences in detail, by the Oglala Lakota Sioux holy man Black Elk (l. 1863-1950) in the works Black Elk Speaks and The Sacred Pipe: Black Elk's Account of the Seven Rites of the Oglala Sioux.

In this story, two young Lakota hunters are out scouting for buffalo when they encounter a mysterious beautiful woman. One of the men lusts after her, approaches her disrespectfully, and is killed, instantly turned into a pile of bones. The other man, who recognized White Buffalo Calf Woman as a holy entity, is told by her to return to his village and announce her arrival.

When she reaches the village, she presents the pipe to the chief, instructs the people on how it is to be used, and teaches them the seven sacred rites that will reestablish their spiritual connection to Wakan Tanka. She tells them that they are to smoke the pipe before all ceremonies and in the making of treaties to bring 'peaceful thoughts' to the mind and send their prayers to the spirit world. After she has completed her instruction, White Buffalo Calf Woman leaves the village, transforms herself into a black, then red, then brown, then white buffalo, and finally vanishes over a distant hill.

The chief remembers her words, especially how "as long as the pipe is used, your people will live and be happy. As soon as it is forgotten, the people will perish," and cares for the pipe until it is passed down to a worthy successor.

Another version of the origin of the Sioux chanunpa focuses specifically on the ritual of the Keeping and Releasing of the Soul, omits the death of the lustful hunter, but otherwise follows along the same lines. The story begins with two young Sioux men out walking in the night talking about love when they see a beautiful young woman approaching them carrying a bundle. One of them lusts after her and says he will make her his wife, but the other prevents him from acting on his impulses.

White Buffalo Calf Woman speaks to them, saying she knows one of them is good and the other evil, and then unwraps her bundle, lays the pipe on the ground, and becomes a buffalo. The buffalo lifts the pipe with its hoof, and she becomes a woman again. She tells the two men that she has come to give them the gift of the pipe that should be used in ceremonies and treaties and how its smoke will be a pleasing offering to the Great Spirit and Mother Earth.

The two young men quickly run to their village and call everyone to come with them to greet White Buffalo Calf Woman. When they all return to where she is waiting, she instructs them in the use of the pipe but adds how, when they perform the ritual of the Keeping and Releasing of the Soul, they must have the skin of a white buffalo. This line is given as "When you set free the ghost, you must have a white buffalo cow skin," but it is unclear whether this means a white buffalo hide must be present at the ritual or whether the people must spiritually resonate as though they have the skin of the white buffalo. After presenting the pipe to the holy men of the village, the woman transforms into a buffalo and hurries away.

Medicine of the Pipe & Tobacco

What the White Buffalo Calf Woman has given to the people is understood as 'medicine' – spiritual power – often connected with health and healing, but these are only two aspects of the physical manifestation of 'medicine' which allows for communion with the spirit world and encouraged the use of the terms 'medicine man' and 'medicine woman' for the shamans or holy people of a community. In giving the people the pipe, the sacred rites, and – in some versions of the story – providing them with the four sacred medicines of cedar, sage, sweetgrass, and tobacco, White Buffalo Calf Woman gives them an open line of communication to their Creator and the unseen world from which all 'medicine' comes.

Black Elk addresses the connection between the people and Wakan Tanka through the pipe in one version of the origin story:

The [sacred] woman then touched the foot of the pipe to the round stone which lay upon the ground and said: "With this pipe you will be bound to all your relatives: your Grandfather and Father, your Grandmother and Mother. This round rock, which is made of the same red stone as the bowl of the pipe, your Father Wakan Tanka has also given to you. It is the Earth, your Grandmother and Mother, and it is where you will live and increase…All of this is sacred and so do not forget! Every dawn as it comes is a holy event, and every day is holy, for the light comes from your Father Wakan Tanka; and also, you must always remember that the two-leggeds and all the other peoples who stand upon this earth are sacred and should be treated as such. From this time on, the holy pipe will stand upon this red Earth, and the two-leggeds will take the pipe and will send their voices to Wakan Tanka."

(The Sacred Pipe, 7)

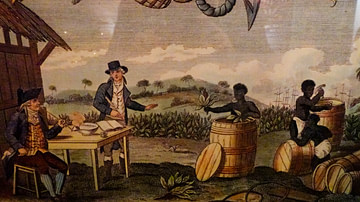

The use of tobacco by Native Americans was and, ritually, still is significantly different from how it has been used by non-natives post-1492. Tobacco, along with cedar, sage, and sweetgrass, was understood as an especially potent 'medicine,' which opened the user to communion with the spirit world. Tobacco could not be sold, was only given as a gift, and was often carried in one's personal 'medicine bag' – a pouch containing items sacred to the individual and often including pieces symbolizing the four elements. Scholar Adele Nozedar comments:

As a sacred herb, tobacco is used to make offerings to the spirits, to the six directions of north, east, south, west, above, and below, and the elements; a pinch could be used to sign a treaty or to assist in the cure of an ailment. Although tobacco was smoked purely for pleasure by Native Americans, its primary use was as a sacred ceremonial herb. It was very rarely taken "neat" but would be mixed up with other herbs – whatever was at hand in the locality. (492)

The tobacco used by the Sioux is now referred to as Nicotiana rustica and, when mixed with other herbs, is (and was) known as kinnikinnick. This mixture was not only used in the pipe ceremony but could also be given as a gift, left as an offering to the spirits of a place after a successful hunt or the harvesting of plants, used as a medicinal agent mixed with water or other herbs, or presented to one's elders as a sign of respect or in thanks for their guidance and wisdom. Tobacco was not used in any of these ways more often than the others, but it is most commonly associated with the pipe ceremony.

In using the ceremonial pipe, one would take a lighted stick from the central fire and touch it to the bowl of tobacco. The first smoke would go up to Wakan Tanka, and the pipe was then offered to the sky above, earth below, and the four cardinal directions before the person holding the pipe drew on it. The smoke was not inhaled, only held in the mouth and then released. If the pipe were being used in a ritual gathering or in signing a treaty involving several people, the person who had lighted the pipe would pass it to the one next to him, and it would go around the circle until it arrived back where it had started.

Making & Meaning of the Pipe

As noted, there is the original pipe presented to the Sioux by White Buffalo Calf Woman and individual pipes carried by others. The bowl of these pipes is usually of stone, most often catlinite, but all the stone, of whatever type, is harvested from the Pipestone Quarry of modern Minnesota. The quarry is still sacred to many different tribal nations, and, in the past, even if two nations were at war, their members could still harvest stone together in peace on the holy ground.

Once the rock was harvested, it was shaped using a bow drill, rough animal hide, and harder to finer abrasives. Once the shape of the bowl was formed, it was hollowed using the bow drill or an arrow point, and this part of the manufacturing process is said to have been the most time-consuming as one needed to proceed slowly and with patience so as not to crack the stone. Once the bowl was completely hollowed through to the end where it would attach to the stem, the pipe was carved with some design or image, rubbed with oil, and polished to a high finish. A stem of hollowed wood, usually decorated, would be attached for use and the two parts separated for storage. One's personal pipe was often carried in one's medicine bag along with one's pouch of tobacco.

Although one might smoke tobacco recreationally in a clay pipe, the stone pipe was used only for ceremonial purposes and always in preparation for and during one of the seven sacred rites. These rites informed the spiritual life of the Sioux, which directed their daily lives and shaped their culture. One's personal pipe, used in preparation for a ritual, was understood as a living thing with its own personal power and was not shared trivially with others or left on display.

Each individual member of the community contributed something to the good of the collective whole, and so it was (and is) with one's personal pipe as well as the original pipe. The sacred, living nature of the pipe – which opened the door to contact with the greater, wider spiritual as well as observable world – was recognized, respected, and protected. The Pluralism Project of Harvard University comments:

The sacred pipe plays a key role in Lakota spiritual and cultural life, and the symbolism and rituals of the sacred pipe provide a good point of entrance into the rich Lakota tradition. However, this ceremony is inseparable from the moral preparation and spiritual reflection that give it meaning in the whole context of Lakota life. Many Lakota and other Native peoples find offensive the popular non-Native notion that ceremonies, such as the sacred pipe ceremony, can be lifted out of context and performed for profit or as a therapeutic weekend diversion. The sacred pipe and its ceremonial use are integrally part of the wider context of Lakota life. (1)

The appropriation of Sioux rites such as the sweat lodge, the Sun Dance, or the pipe ceremony by non-Natives for commercial purposes, even if meant in the best spirit, is discouraged by the Sioux as cultural appropriation of the worst sort.

Conclusion

The sacred pipe ceremony is still observed today by the Sioux as it was in the past and non-Natives are not allowed to participate unless they have been adopted by the people for whatever reason. Stone is still harvested from the Pipestone Quarry at the Pipestone National Monument, now a United States National Park, as it has been for 3,000 years, and pipes are made by multigenerational craftspeople who have kept alive the processes observed in the ancient past. The original pipe, given to the people by White Buffalo Calf Woman, is still cared for by a spiritual leader, just as it was when first received. Scholars Yvonne Wakim Dennis et al. comment:

Arvol Looking Horse is the nineteenth-generation keeper of the Sacred Pipe of the Great Sioux Nation, which was given to the Lakota by White Buffalo Calf Woman long ago. He received this responsibility at the age of twelve, when he was living with his grandparents on the Cheyenne River Reservation. The essence of Sioux identity and culture, which Black Elk referred to as the sacred hoop, was thought to have been broken after the massacres, land loss, and destruction of the buffalo herds on the Plains. However, prophesy also maintains that healing and restoration of Native Life will begin in the Seventh Generation after these suppressions. Looking Horse believes his people are living in the time of the Seventh Generation and that his caring for the pipe will help mend the sacred hoop. (217-218)

Arvol Looking Horse may well be right in that there has been a heightened interest in Native American spirituality and culture recently on a wider and more sustained level than that of the late 1960s and early 1970s. When White Buffalo Calf Woman gave the sacred pipe to the Sioux, she told them that, in using it, they would be praying with and for all things in creation, not just themselves, opening all to communion with the Great Spirit. As awareness of the injustices suffered by Native Americans in the past grows, along with a resurgence of Native American culture and restoration of language, and as more of their legal battles are won, it seems their prayers in this regard are being answered.