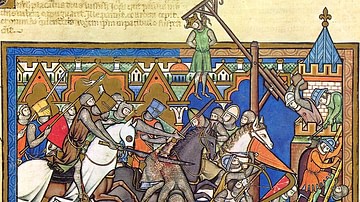

The Siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE was the high watermark in the First Jewish-Roman War (66-73 CE) regarding the tension between the two forces. With the Roman Empire transitioning from the Julio-Claudian emperors to the Flavian dynasty in the middle of 69 CE, there was much pressure to quell the rebellion across Judaea.

The Great Jewish Revolt

Due to religious tumult and increased taxation under the last Julio-Claudian Emperor Nero (r. 54-68), there was open discontent between the people of Judaea and the Roman government. With protests breaking out, the Procurator (a Roman governor of sorts) Gessius Florus plundered the Second Temple (in Jerusalem), claiming the money for the empire. This action, coupled with the preexisting tensions, prompted uprisings to spread across all of Judaea, beginning the First Jewish-Roman War.

With the rebellion gaining momentum, General Vespasian, of the Roman Empire, was appointed to handle the unrest in Judaea. With his son, Titus, by his side, he effectively choked the revolution by claiming strongholds that surrounded the main fortress of Jerusalem. Two years into the revolt, though, Nero committed suicide and ushered in the year of Four Emperors. Ultimately, Vespasian (r. 69-79) would secure the throne with support from the legions under his command, and he would return to Rome. He left Judaea, and his son Titus took control of the legions and continued to battle the Jews. On April 14th, 70, Titus and the Roman army marched on Jerusalem. This day was only three days before the Passover that year which in part was the cause of the increased population of Jerusalem.

Jerusalem before the Siege

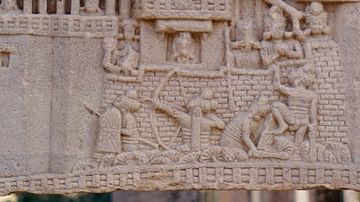

Jerusalem was a very defensible position at the time of the siege. The city was built amidst valleys; it was elevated and thereby difficult to breach. Surrounded by a wall, Jerusalem had been divided into sections designated the Upper City on the westside where more affluent citizens resided, and Temple Mount on the east end of the city. Just north of the Temple, there was the Fortress of Antonia. A second wall protected them on the north, beginning at the Fortress. During the war, the people of Jerusalem completed the outermost third wall.

With many of the other Jewish strongholds already conquered and the Passover occurring, many people had flocked to Jerusalem. We do not know whether for political or religious purposes, but there was undoubtedly an influx of people in the city when the Roman armies arrived and established a perimeter. With so many people there and the war going poorly for Judaea, there were numerous factions within the rebellion, resulting in much infighting. In Jerusalem specifically, this issue caused losses in human resources and consumed much of the food reserves previously stored. The two prominent leaders of the factions in the city were Simon bar Gioras and John of Gischalla. Simon and his group controlled the Upper City and Herod's palace in the west, while John and his men maintained their position on the Temple Mount. With Rome approaching, the fighting would soon begin.

Establishing Camp & Getting Through the Third Wall

Titus and his legions arrived on 14 April of the year 70 CE. Upon arrival, Titus rode out with scouts to survey the areas around the Temple. At this point, the rebels struck Titus' scouting party and nearly killed the general. Caught unprepared and out of formation, the Romans lost many men in this quick fight. Following the skirmish between the scouts and Jewish soldiers, the Romans established a camp east of the city at the Mt. of Olives. Seeing that there were seemingly endless obstructions of vegetation, Titus commanded that the terrain be cut down and flattened to increase visibility and mobility for siege equipment. They were now prepared to begin the siege in full with their base camp established.

At this point, Titus set up two more camps northwest of the city. The Romans began by engineering ramps up the third wall. Launching missiles at the construction crew, the Jews would not give up the wall without a fight. Romans covered the construction of the ramps by using their artillery in response. Titus' army took only 15 days to breach the outermost wall despite the rebels’ best efforts. Rome built a new camp, and the Jews retreated within the second wall. The momentum led to a rapid breach of the second wall. It only took four days to get through that wall.

Stalemate within the Second Wall

Up until this moment, Rome was making steady progress towards conquering the stronghold. Only about 20 days into the siege, Titus had penetrated the city's second layer of defense. The legionnaires funneled through as soon as a hole was punched through that wall. As they made their way through the town towards the last barrier, the rebels ambushed them. The breach was so narrow that only two or three could make it back out. The gap was narrow enough to form a choke point, and the insurgents slaughtered the professional soldiers. The rout was not devastating, but the morale faltered in the Roman camps that night.

With the most recent defeat fresh in the minds of both armies, Titus ordered a wall of circumvallation to be built. His goal was to distract his legions from dwelling on losses and restrict food from being smuggled into Jerusalem. Titus remounted the assault on the second wall, and this time, once the army was within, he ordered the entire wall destroyed except for the towers. Rebel leaders ordered a retreat within the inner wall.

With the smaller perimeter, it became much easier for the Jews to hold this line. The thicker, taller walls of the Fortress of Antonia made it a more defensible position, and it is here that the outcome of the siege would pivot. As with the other walls, Titus ordered ramps to be built, and battering rams and siege towers rolled up to the walls. After 17 days, the preparations were finished, and Rome was ready to assault the fortress. Unbeknownst to the Romans, the Jews had dug a mine that traveled directly underneath the newly built ramp. The mine was filled with fuel and then set on fire. The mine collapsed the engineering project, and when the fires surfaced, they ignited the siege equipment. The resourcefulness of the defenders cannot be underestimated here. Using every resource they had, they were able to frustrate a well-oiled military machine.

The victory in the mine was short-lived. When the fires were extinguished, Titus ordered an assault on the fortress. While the mine was ingenious, it had a fatal flaw. It weakened the fort's foundation, and after one day of the assault, the wall collapsed. The Romans had penetrated the first wall and had gotten a foothold on the Temple Mount.

Four Battles in the Temple

This siege, in particular, demonstrates well the determination of the two forces - the Jews fighting for their survival and the Romans displaying discipline from their training. When the fortresses' walls fell, the Romans found new challenges from their opposition.

With a breach in the wall, a small contingency of soldiers attacked in the night. It is worth mentioning that they did this without orders. When the defenders realized that it was not the entire Roman force, they rallied to prevent the Romans from gaining a more powerful position. Roman reinforcements soon came, and a full-scale battle commenced. With the slight advantage of getting in position sooner, the Jews found victory at the end of the First Battle of the Temple.

At this time, Titus commanded that the fortress be wholly destroyed. A new assault was mounted during the night. The legionnaires were highly trained, but the area was too confined, and the chaos was too much to operate most effectively. The battle lasted into the daytime, but neither side could take the advantage. Ultimately, they fought the Second Battle of the Temple to a draw. Sometime after the conclusion of this battle, the rebels lured the Romans onto the Temple's outer walls. The Jews retreated in the hope that they could get as many of the enemy as possible on the walls before the defenders ignited the colonnade from which they had just withdrawn. Soldiers caught in an inferno atop the walls were seen by both sides of the battle. This victory once again bolstered Jewish morale while adversely affecting the Romans.

In the Third Battle of the Temple, Titus destroyed the whole northern colonnade to allow a wider opening for his troops. The open area made it possible to push forward in formation and gave the attackers an incredible advantage. With the defenders confined to the inner Temple, defeat seemed imminent for the Jews. Instead of the Romans going on the offensive, the Jews sallied and attacked the enemy lines. However, surprised, Titus' men held their lines. They fought for several hours, but neither side gained any ground. Ultimately it was a draw.

Increasingly desperate, the Jews attacked again. This time, however, the Romans not only held their lines but pushed back. Pinning the rebels against the Temple, they fought in confined spaces again. Once more, without orders, a few legionnaires took the initiative and started a fire in the Temple. The chaos that ensued was in the attacker's favor, and the Romans won the day. Storming the Temple, the Romans plundered it for its riches. Thus, concluded to Fourth Battle of the Temple.

Rome Takes the Rest of Jerusalem

The remainder of the siege came with ease to the Romans. After Titus claimed the Temple and made his own sacrifices within its walls, there was a request by the two Jewish leaders, Simon and John. They attempted to negotiate a way out of the city, but Titus would not cede any advantage to them. Instead, Titus ordered a portion of the city to be sacked and burned. Rome pushed the rebel forces back to the upper city and Herod's palace, where they would make their last stand.

Significantly weakened, the Jews were unable to defend themselves in the same manner as they had before. Titus surrounded the rebels by placing siege units inside the city and flanking from the outside of the wall. Without the manpower to defend, Jerusalem had been conquered.

Fallout after the Siege

Rome dealt out its punishments with the battle concluded and the victors in charge. It is estimated by the ancient historians Tacitus (l. c. 56 - c. 118 CE) and Flavius Josephus (36-100 CE) that there were about 600,000 to 1,100,000 people killed in the siege. Males aged 17 and older were either put in hard labor camps or made to be gladiators. Women and children were sold into slavery. For the two leaders, Simon bar Gioras and John of Gischalla, Titus had other plans. The two were taken back to Rome, paraded through the streets as prisoners, and publicly judged. John was sentenced to imprisonment while Simon was judged, flailed, and then executed.

After the siege, the First Jewish-Roman War would still be fought for three more years. Other notable sieges would happen, such as the mass suicide in Masada. In the end, though, the Romans would be the victors. Ultimately, the Siege of Jerusalem was no ordinary siege. The lasting effects it had on the Roman Empire cannot be quantified but undoubtedly changed the nation's course. The victory legitimized Vespasian and Titus as capable emperors to begin the Flavian Dynasty.