Gothic cathedrals are some of the most recognizable and magnificent architectural feats. With soaring towers and softly filtered light streaming through stained glass windows, everything about the Gothic cathedral is transportive and ethereal, lifting the gaze of the viewer towards the heavens. Architectural innovations, such as flying buttresses, were essential to creating the Gothic style, but it was the new, intentional use of light that truly set Gothic architecture apart from its heavier and darker Romanesque predecessors.

The Gothic style originated in 12th-century CE France in a suburb north of Paris, conceived of by Abbot Suger (1081-1151 CE), a powerful figure in French history and the mastermind behind the first-ever Gothic cathedral, the Basilica of Saint-Denis. For Suger, and other like-minded medieval theologians, light itself was divine and could be used to elevate human consciousness from an earthly realm to a heavenly one. Suger, and those who came after him, attempted to flood their cathedrals and abbeys with light, building taller and more elegant structures. This necessitated the adoption of some of the most obvious aspects of the Gothic form; pointed arches, rib vaults, and flying buttresses could be used to make the walls taller and thinner by distributing the weight of the building more effectively.

Not everyone was a fan of the Gothic style. Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574 CE), the Italian artist and writer whose works are considered to form the basis of modern art historical study, retrospectively named the style pioneered by Suger as “Gothic,” which was meant to be derogatory. Writing in the late 16th century CE after the Gothic style had fallen out of favor, Vasari saw the style as degraded when compared to the classical forms of the Renaissance architecture of his own era. By calling it Gothic, he attempted to liken the style to the “barbaric” Goths that had invaded Rome over a thousand years earlier. Even so, Vasari's disapproval did not stop the Gothic revival from taking root in the late 18th century CE, and today millions of people each year continue to be captivated by the unearthly majesty of Gothic cathedrals.

Architectural Components

Preceded by the Romanesque style and followed by Renaissance architecture, the Gothic style was popular throughout Europe from the 12th century through the 16th century. Gothic architecture did away with the thick, heavy walls, and rounded arches associated with Romanesque architecture by using flying buttresses and ribbed vaulting to relieve the thrust of the building outward, allowing thinner and taller walls to be constructed. Gothic churches could achieve new heights with a lightness and a gracefulness often absent from sturdy Romanesque structures. Some of the key architectural components integral to the Gothic form are pointed arches, flying buttresses, tri-portal west façades, rib vaults, and of course, rose windows.

Pointed Arches

As opposed to the rounded arches commonly found in Romanesque buildings, Gothic structures are famous for their pointed arches that proved more adept at bearing weight. These pointed arches were not only used for practical reasons; they were symbolically significant in that they pointed towards heaven. The pointed arch, though not exclusively found in Gothic architecture, became one of the defining characteristics of the style.

Flying Buttresses

Whereas Romanesque buildings had used internal buttresses as a means of supporting weight, the buttresses of Gothic cathedrals are external. These so-called flying buttresses allowed for churches to be built much taller, as the weight of the roof was dispersed away from the walls to an external load-bearing skeleton. Pushing back against the outward thrust of the walls, flying buttresses allowed for the soaring heights and tall central naves of the Gothic cathedral.

Tri-Portal West Façades

Another unique feature of the Gothic cathedral is the west façade, often seen as the front of the church, which typically consists of two towers, a central rose window, and three entranceways. The west façade of the Notre-Dame in Paris, for example, is where the crowds congregate to gaze up at the elaborate carvings that adorn the building. Elaborate sculptures carved into the tympanum above each doorway tell a story that a largely illiterate medieval population could understand. The central portal at Notre-Dame is known as the Portal of the Last Judgement, the left portal as the Portal of the Virgin, and the right as the Portal of Saint Anne.

Rib Vaults

Ribbed vaulting is an essential technique that allowed for the overall increase in size and intricacy of design in Gothic structures. Romanesque structures had generally used barrel vaults and groin vaults. Gothic structures, on the other hand, used a diagonal framework known as rib vaults, enabling the building of taller and thinner structures. In a Gothic cathedral, it is easy to spot the rib vaults crisscrossing the ceiling of the central nave.

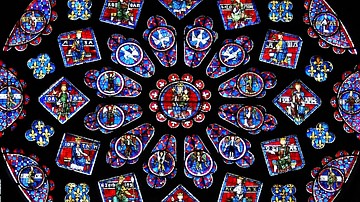

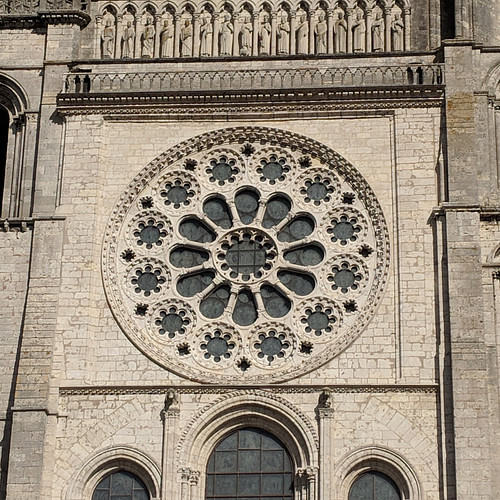

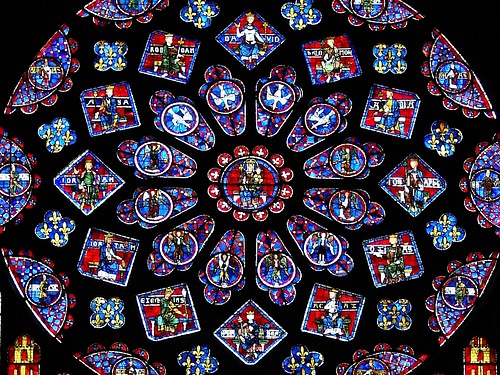

Rose Windows

Visitors to Gothic cathedrals are usually struck by the ethereal purple light streaming in from enormous, circular windows known as rose windows. Taller buildings allowed for taller windows in general, but the use of stone tracery to reinforce stained glass windows also made larger windows possible. Additionally, the use of silver stain in the production of stained glass in the 13th century CE allowed for the creation of a clearer glass, further brightening the interior of Gothic structures. Though examples of circular windows can be found in some Romanesque churches prior to the Gothic period, the rose window became a defining feature of Gothic cathedrals, and with the development of stone tracery techniques that enabled more panels of glass to be secured into place, they grew to new proportions. Chartres Cathedral, completed in the early 13th century CE and located southwest of Paris, has perhaps the most impressive surviving collection of stained glass dating back to the medieval era.

The Birth of Gothic: Abbot Suger & Saint-Denis

Abbot Suger (1081-1151 CE) was a powerful figure in France at an important time in French history when the monarchy's power was increasing. Advisor to both Louis VI (1081-1137 CE) and Louis VII (1120-1180 CE), Suger held the position of regent when Louis VII left for the Second Crusade (1147-1150 CE), which essentially left Suger in charge of France. Appointed abbot of Saint-Denis in 1122 CE, Suger held the position for nearly 30 years until his death. Between the years of 1137 and 1148 CE, he embarked upon an ambitious project to transform the church into a physical manifestation of the divine, creating what would become the archetype of the Gothic cathedral. Suger extensively documented his renovations and reasonings in his writings known as The Book of Suger, Abbot of Saint-Denis: On What Was Done Under His Administration.

Suger's renovations began with the west façade of the church. The addition of three portals on a west-facing façade, as well as the soon-to-be ubiquitous rose window, are essentially innovations of Suger. Largely influenced by Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite's metaphysical understanding of light, Suger believed that luminous and beautiful material objects could help spiritually transport the beholder towards the divine realm. For Suger, the church occupied a sort of liminal space between the earthly and heavenly realms. The intentional use of light, therefore, was a driving force behind his renovations, the main reason for bringing together the defining architectural characteristics of the Gothic style in a single building for the first time. Suger's infatuation with light is exemplified by the words he had inscribed on one of the cathedral's gilded bronze doors:

All you who seek to honor these doors,

Marvel not at the gold and expense but at the

craftsmanship of the work.

The noble work is bright, but, being nobly bright, the work

Should brighten the minds, allowing them to travel through

the lights

To the true light, where Christ is the true door.

The golden door defines how it is imminent in these things.

The dull mind rises to the truth through material things,

And is resurrected from its former submersion when the

light is seen. (Suger & Panofsky, 23)

Suger believed his brighter church would "brighten the minds" of his congregation, leading "to the true light, where Christ is the true door." He also specifically states that material objects can serve as channels for the divine truth: "the dull mind rises to the truth through material things." A medieval theological understanding of materiality to which Suger subscribed held that all material objects had the capacity to be vessels of the divine. Suger justified his elaborate renovations and decorations of gold and precious gems because he saw them as literal conduits of the divine. The prevailing belief in the Middle Ages was that material objects, the fancier and more beautiful the better, could be instruments for connecting with God, and the key ingredient for activating these objects was light. The use of light in Gothic cathedrals, therefore, became an architectural technique in its own right; it was just as important to the construction of a Gothic cathedral as flying buttresses and ribbed vaulting. Light was seen as literally being of the divine realm, and Suger took great care to eliminate any obstruction to the calculated flow of the divine light throughout Saint-Denis.

Light as a Guiding Force

In the Middle Ages, there were important epistemological distinctions between the concepts of lux, lumen, and splendor, words used to describe light with varying levels of metaphysical attributes. While lux refers to the natural light emitted from the sun, lumen is light as it interacts with the material world, and splendor is reflected light. For Suger and those who followed in his footsteps, the point was not to simply flood the entire church with as much light as possible but to harness lux, lumen, and splendor in specific ways. The addition of the rose window at Saint-Denis is a strong example of the use of light to guide the viewer's sight to a higher plane, both literally high above, but also symbolically as a model of the divine realm. The west rose window at Saint-Denis occupies what MIT Professor of Architecture, Dr. Mark Jarzombek, calls a “strange space in our architectural imagination,” not simply a producer of light, but “a floating signifier of Heaven,” (Lecture 21 in A Global History of Architecture via edX).

Another example of guiding light in Gothic cathedrals is at Chartres Cathedral, where the side aisles form a bright outline of the nave, drawing viewers along the widest nave of any cathedral in France. The interior brightness of Gothic cathedrals increased from the 12th to 13th centuries CE, from the period of Early Gothic to Late Gothic (sometimes referred to as Early Renaissance). Part of this change can be attributed to the development of white-colored stained glass. Another interesting phenomenon is the gradual enlargement of the rose window in various cathedrals, beginning with Saint-Denis. A larger rose window is present at Chartres, while the rose window at Westminster Abbey is so large that it touches up against the balustrades that frame it on either side.

Underlying these shifts are changing philosophical beliefs that manifested directly in ecclesiastical architecture. As the Middle Ages seceded to the Renaissance, the metaphysical conception of light gave way to a more scientific understanding. This change in the belief of the nature of light was a shift from a literal understanding of light as the embodiment of divinity, to a symbolic one where light was a representation of the divine. The way in which light needed to interact with the material world, and the very way in which the materiality of light itself was portrayed and utilized, changed. As it became more scientifically and less metaphysically understood, perhaps light became a metaphor for the divine, as opposed to the real thing. Even so, it is impossible to understand what the Gothic form meant to the medieval people for whom these structures were built without first understanding their beliefs concerning light and materiality that informed and inspired these fascinating and beautiful architectural developments.