Since the return to democracy in Chile in 1990 CE, the new governments have dealt with one of the great historical debts of the Chilean state, its relationship with the indigenous peoples. These peoples have been historically marginalized and made invisible in all spheres. However, with the revaluation of their cultural heritage, indigenous medicine and the use of elements of nature and medicinal herbs - wisdom accumulated for centuries - re-emerges. Through the Special Program of Health and Indigenous Peoples (PESPI by its Spanish acronym, Programa Especial de Salud y Pueblos Indígenas), present in almost all health services in Chile, indigenous medicine has become available for the whole population as a valued alternative within the official medical system. This programme promotes complementarity between the conventional and indigenous medical systems, incorporating intercultural medical assistance in hospital and primary care facilities.

Traditional Mapuche Health

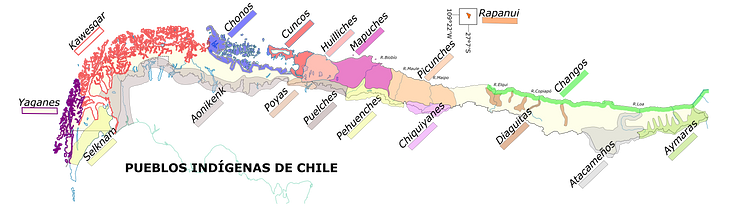

The PESPI programme promotes the indigenous health of each of the peoples recognized by the Chilean State (Chile recognizes 9 indigenous peoples) and the complementarity with the official medical system. The public health strategy is to establish a link between the hegemonic medical system and the alternative one, reinforced and supported by the recommendations of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO):

This perspective assumes, therefore, that medical systems alone are not sufficient to meet the health demands of an indigenous population, both in their conceptions of health and disease and in the way they carry out healing. (Manriquez-Hizaut et al., 760)

The Mapuche people are the most numerous and have the greatest presence in the urban context, particularly in Santiago where nearly a third of Chile's indigenous population lives. Their conception of illness and health is quite different from the one we know today, and this diverse view has generated interest not only among the Chilean indigenous population who value this ancestral wisdom but also among the non-indigenous population and the health teams in care facilities.

Mapuche medicine understands health as a balance basically in two areas. Firstly, the person is conceived as an "open body", as opposed to the modern view of a closed and divided body (inaugurated with Descartes): "The integrative conception of the body or "open body" leads its people to live illness and health as states of the body in relation to its social environment: "wezafelen" or being bad and "kumel kalen" or being good" (Solar, 2005, 2).

The idea of kumel kalen or küme mongen (to be well, to live well) is also present in other Latin American cultures under the concepts of Sumak Kawsay in Quechua or Suma Qamaña in Aymara for example. The illness is then understood as a lack of respect or imbalance of the individual with its environment. This can happen through the transgression of laws, rites, or the forbidden. In this way, "the evil is not the disease, but the cause that produced it and thus considers the disease not as an evil, but as a reaction to the evil" (Solar, 4).

Secondly, the Mapuche worldview sees the universe or the whole as a unit made up of opposite and

complementary poles. Likewise, health (Konalen) and illness (Kutran) are in constant tension, making it

impossible to see the body as an isolated unit, but rather as an open entity that reflects the tensions and

balance of the world. Thus, in order to incorporate the indigenous approach to the traditional health system, the only way is to talk about complementarity, that is, a relationship that allows health teams to get closer to indigenous medicine specialists (machi or lawentuchefe), that allows for the derivation and exchange of knowledge when necessary.

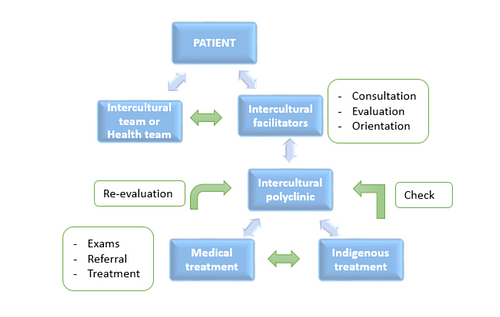

Intercultural Model: Traiguén Intercultural Polyclinic, Dino Stagno Hospital

In Traiguen (IX region of the Araucania), where indigenous health is more developed due to the high concentration of Mapuche population, the Dino Stagno Hospital has a Polyclinic for intercultural care in addition to the typical services of a hospital. This space began to take shape in 2006 CE thanks to the Amuldungun (orientation) office, managed by two indigenous people. They are known as intercultural facilitators (a mediating link between the public institutional provider and indigenous individuals, families, and communities), who receive indigenous or non-indigenous patients who need the care of a traditional Mapuche medicine agent through two mechanisms:

- Direct consultation with the Amuldungun office: The intercultural facilitators interviews the patient and according to the data collected estimate the relevance of an indigenous medical agent (either lawentuchefe or machi).

- At the request of a professional from the health team: If a professional from the hospital considers the intervention of intercultural facilitators to be necessary or considers the relevance of traditional agent care, the facilitators are summoned and, together with the professional, evaluate the case for subsequent referral to a machi or lawentuchefe.

In the latter mechanism, intercultural facilitators participate in a patient's diagnosis, whether the patient deems it necessary or the health professional thinks it is appropriate. In this way, intercultural health achieves the aim to mainstream its approach, and to be present in every view of the different health disciplines. On the other hand, when, according to the lawentuchefe or intercultural facilitators, the problem or unhealthiness exceeds their capabilities, the possibility of referring to machi is evaluated. The hospital supports patients with the transfer, since the machi only attends in his/her rehue (sacred space), thus allowing a complementarity based on respect for the indigenous medical system and its traditions.

Derivation Model

This referral model therefore allows for complementarity and joint work between indigenous medicine agents and health teams, referring and counter-referring patients depending on each other's assessments. It has the advantage of including a diverse view of the disease, since many times it does not have a monocausal origin but can be manifested precisely by an imbalance between the patient and his or her environment.

Indigenous Medicine & Tourism as Promoters of Well-being & Conservation of Tradition

While traditional indigenous medicine has been revalued and promoted in recent decades by both the non-indigenous population and health teams, tourism can also play an important role in strengthening and preserving these traditions.

As a promoter of well-being, tourism can generate income and at the same time create new employment opportunities for communities. However, it must be the indigenous communities themselves who organize and manage access to services and cultural heritage, otherwise there is a risk that the benefits generated by these activities will fall into the hands of tourism operators. For example, a study in Mexico found that indigenous medical tourism can be a driver of well-being for their populations:

Tourism activities oriented towards the development of a community, in this case through the safeguarding of traditional medicine, are drivers of community benefits, channeled to improve the quality of life of the community in general, acting as generators of well-being in the entity where they are employed, whether in economic, social, cultural and environmental matters. (Gutierrez Delgado et al., 413)

In fact, tourism has an important role in the sustainable development goals of the United Nations, and

sustainable, community-organized management can bring benefits at all levels.

- Valuation of traditional collective knowledge and technologies applied to production, food, and health.

- Strengthening the historical heritage, cultural identity, and collective esteem that make the destination attractive for tourism.

Although tourism is not the ultimate solution to the problems of indigenous peoples in their constant effort to be recognized and made visible, it can be an important tool for, in addition to other activities, achieving significant development of the communities, as well as in the valorization of the intangible cultural heritage of these peoples.

Final Considerations

Indigenous intercultural health has significant potential both at the level of heritage and tourism. There is also the advantage that the model of complementarity has been operating for several years in Chile and, with its successes and errors, has managed to establish a valid alternative to the official medical system. These models of implementation and derivation can be used to establish a strategy of diffusion at an international tourist level for the attention of non-indigenous people who look for a different answer to their health problems, both physical and psychological. In this respect, not only in Chile do these types of experiences exist but also in other South American countries traditional indigenous medicine is used to treat even drug dependency.

There is significant potential to promote the well-being and conservation of indigenous tradition, making it known to the world and in turn benefiting communities through tourism strategies based strictly on sustainability and the active participation of the communities involved. To this end, governments must ensure adequate conditions for equitable development that respects the rights of local populations through a comprehensive policy.

This article was submitted as part of Ancient History Encyclopedia's UNESCO Summer School scholarship programme.