Tlaltecuhtli, 'Earth Lord/Lady,' was a Mesoamerican earth goddess associated with fertility. Envisioned as a terrible toad monster, her dismembered body gave rise to the world in the Aztec creation myth of the 5th and final cosmos. As a source of life, it was thought necessary to constantly appease her with blood sacrifices, especially human hearts.

Name & Attributes

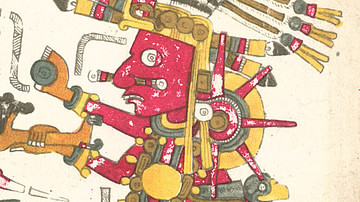

Envisioned as a goddess but perhaps possessing dual gender like one or two other Mesoamerican primordial deities, Tlaltecuhtli, with its male suffix, may be literally translated as 'Earth Lord' or, more typically 'Earth Lady.' The goddess was imagined as a fat toad-like monster with a big mouth, fangs, and clawed feet. Considered the source of all living things she had to be kept benevolent by blood sacrifices which would ensure the continued order of the world.

The Creation Myth

The idea of a creation myth involving a savage aquatic monster with crocodile features goes back to the Classic Maya and the 5th century BCE, a figure which was perhaps based on a similar shark-like monster in even earlier Olmec mythology. In the creation mythology of the Aztecs and other Mesoamerican cultures of the Late Postclassic period (13th-16th century CE), the gods Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca, taking the form of gigantic snakes, descended from the heavens one day and found Tlaltecuhtli sitting astride the ocean. In some versions, this creature is known as Cipactl or 'spiny one.' The hideous monster, with large fangs, crocodile skin, and gnashing mouths at her elbows and knees, called menacingly for flesh to feast on. The two gods realised that the 5th and final cosmos could not possibly prosper with such a fiendish creature roaming the world and so they took it upon themselves to destroy her. A mighty tussle ensued in which Tezcatlipoca lost his left foot. Finally, one god took the right hand and left foot while the other took the left hand and the right foot, and with a mighty heave, they managed to rip Tlaltecuhtli in two. From the upper half came the sky and the other lower half became the earth.

The other gods were not best pleased to hear of Tlatecuhtli's treatment and so decreed that the various parts of her dismembered body should give rise to features of the new world. Thus, her skin became grasses and small flowers; her hair became the trees, flowers, and herbs; her eyes became springs and wells; her nose became the smaller mountains and valleys; her shoulders the larger mountains; and her mouth became the caves and rivers.

Despite being ripped to pieces and transformed into geographical features, the Mesoamericans still continued to think of Tlaltecuhtli as an earth goddess, and they attributed any strange sounds coming from such features as either the screams of Tlaltecuhtli in her dismembered agony or her calls for human blood to feed her. Indeed, the goddess gained a reputation for having an insatiable appetite for the hearts of sacrificial victims. This appetite had to be satisfied or the goddess would cease her nourishment of the earth and crops would fail.

Another aspect of the goddess was that Tlaltecuhtli was thought to swallow the sun every evening and regurgitate it the next morning at dawn. This solar connection ensured she was part of the prayers offered to Tezcatlipoca before an Aztec military campaign. Finally, midwives called on her aid during difficult births, and she appears in the Aztec calendar as the 2nd of the 13 Lords of the Day, with her date glyph being 1 Rabbit.

Representation in Art

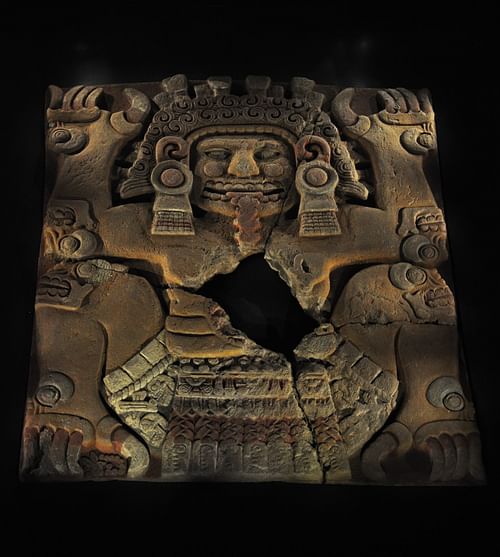

Tlaltecuhtli, in various forms, is an ancient Mesoamerican deity but the earliest representations in sculpture are found at the Maya city of Mayapan in Yucatan. These date to the Late Postclassic period. More common in Aztec art, the goddess is often represented as a spread-eagled figure representing the hocker or squat adopted when giving birth. Her mouth usually gapes with fangs or teeth of flint blades, and she may have the skin of a crocodile which represents the surface of the earth.

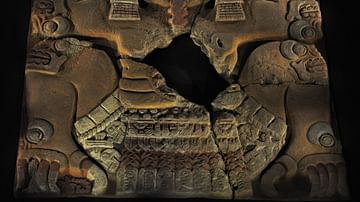

The most famous representation of Tlaltecuhtli is on the colossal stone slab found near the base of the Templo Mayor of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan (now central Mexico City). The pink andesite stone was broken into four pieces by the weight of a colonial building once above it. Put back together, it measures 4 x 3.5 metres and weighs around 12 tons. Carved in high relief on the stone is the familiar squatting figure of Tlaltecuhtli wearing a skull and bones dress and with a river of blood flowing into her gaping mouth. The stone may have been used to mark a royal burial, perhaps that of Ahuitzotl, as indicated by a year glyph (10 Rabbit or 1502 CE) and the nature of the goods buried under it, which are still being studied by archaeologists.

Another representation of the goddess is found on all four sides of the 1503 CE Coronation Stone of the Aztec ruler Montezuma II (aka Motecuhzoma II), and with her, the glyphs for water and fire, traditional symbols of war. The historian M. E. Miller is of the opinion that the face in the centre of the celebrated Aztec Sun Stone (aka Calendar Stone) is, in fact, Tlaltecuhtli and she there symbolises the demise of the 5th and final sun of the Aztec cosmos.

The goddess was often carved onto the bottom of sculptures where the base touched the earth and on the undersides of the special stone boxes known as cuauhxicalli ('eagle box') which were used to keep the sacrificed hearts she was so partial to. Finally, Tlaltecuhtli appears as a fanged toad monster in the form of a cornerstone of a pyramid platform at El Tajin. This links the architectural function of the stone as supporting the pyramid to her mythological function of supporting the earth.