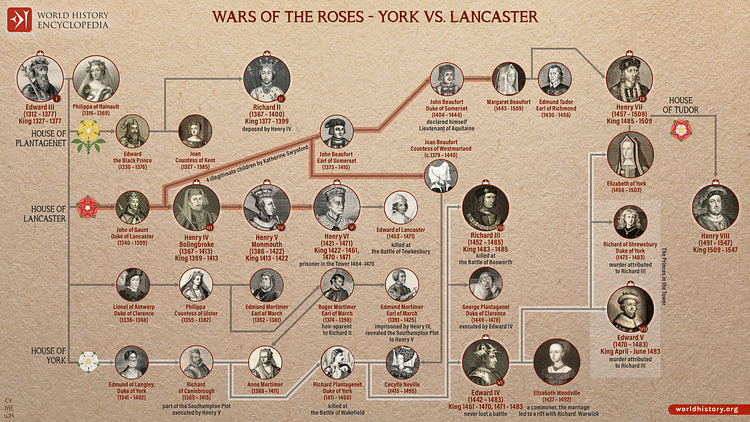

The Tragedy of Richard III, often referred to as simply Richard III, is a history play by William Shakespeare (1564-1616), probably written around 1592-94. It is the fourth and final installment of the 'first tetralogy' of Shakespeare's history plays which, along with the three parts of Henry VI, chronicle the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487), a series of bloody dynastic conflicts in England that pitted the houses of York and Lancaster against one another. Richard III picks up toward the end of the conflict and follows the Machiavellian rise of the hunchbacked Richard, Duke of Gloucester, as he schemes and murders his way to the English throne, eventually becoming King Richard III of England (r. 1483-1485).

Background & Context

At the time that Richard III was written, history plays were quite popular in London – Shakespeare, still in the early part of his career, would have been encouraged by the success of his Henry VI plays to continue the story where he left off, with the death of the Lancastrian King Henry VI of England (r. 1422-1461; 1470-1471) and the reacsension of the Yorkist claimant King Edward IV of England (r. 1461-1470; 1471-1483). Richard, Duke of Gloucester, is the youngest brother of King Edward and suffers from several physical deformities, including a twisted spine and a withered arm. According to Richard himself, these deformities have caused him a life of mockery and unlovability, and have made him decide to "prove a villain"; from his very first appearance in Act I, he stops at nothing to claw his way to the throne, ordering the deaths of his brother Clarence, the Princes in the Tower, and his wife.

Richard takes the audience along for the ride – early in the play, he addresses them and takes them into his confidence, winning them over with his wit and good humor. Indeed, Richard plays the part of 'Vice', a character that expresses sinister intentions through comic charm, common to the morality plays of medieval literature – in the words of scholar Peter Holland, Richard's charm makes it "almost impossible for spectators to maintain their moral ambiguity" (906). Only after he takes the throne does Richard lose the audience's sympathy; as he becomes more paranoid and isolated, so, too, does he stop addressing the audience, thereby removing them from the spell of his charm.

The depiction of Richard III as a deformed villain – albeit a charming one – was not original to Shakespeare. In the decades after the defeat and death of the historical Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field (1485), it was in the best interest of the Tudor dynasty that had supplanted him to paint him as a bloodthirsty tyrant. The Tudors, whose rise to power marked the end of the Wars of the Roses, propagandized their victory over Richard as a battle of good versus evil, their victory at Bosworth a "divinely sanctioned deliverance of the English nation" (Bevington, 263). It was in the best interest of contemporary chroniclers to align their own depictions of Richard with this Tudor propaganda.

The villainization of Richard began with Sir Thomas More and his work The History of Richard III, and it was propagated in Edward Hall's The Union of the Two Noble and Austere Families of Lancaster and York (1547) as well as in Richard Holinshed's The Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland (1577). Shakespeare, who drew on all three of these works, would have been unable to resist the delightfully devilish image of Richard that they had created. Many of the myths about Richard III that persist in the modern imagination were immortalized by Shakespeare, such as the idea that he had his nephews, the Princes in the Tower, killed, or that he was as deformed as he is depicted. Shakespeare's play aligns with the Tudor version of history by depicting the Earl of Richmond – the future Henry VII of England, founder of the Tudor dynasty – as a heroic force of good, who defeats Richard, the "demonized epitome of evil" (Holland, 904). But whatever liberties the chroniclers and Shakespeare may have taken with Richard's character, the villain they have created – a violent, paranoid, authoritarian – comes to life with uncomfortable realism, mirroring several real-life dictators and autocrats.

Synopsis: Acts I & II

As the play opens, the Yorkist King Edward IV has reascended the throne after defeating his Lancastrian enemies at the Battle of Tewkesbury. His opponent, the Lancastrian King Henry VI, is dead – murdered by Richard at the end of the previous play, Henry VI, Part 3 – and after years of bloody conflict, it seems that England is finally at peace. But this peace does not suit Richard, Duke of Gloucester, the new king's youngest brother. In his famous soliloquy that begins "Now is the winter of our discontent / Made glorious summer by this son of York", the hunchbacked Richard tells the audience that someone as ugly, unloved, and deformed as he can find no room for advancement in times of peace. "Since I cannot prove a lover," he explains, "I am determined to prove a villain" (1.1.28-30). He has already lain the groundwork for his schemes – by referencing a prophecy that the king will be murdered by someone whose name starts with the letter 'G', Richard has convinced King Edward that their middle brother, George, Duke of Clarence, is plotting against him. Clarence is arrested and taken to the Tower of London, where Richard tells him that Edward's wife, Queen Elizabeth Woodville, has orchestrated his arrest. Richard promises to do his best to help Clarence and 'deliver' him from his imprisonment.

The next part of Richard's plan is to marry Lady Anne Neville, widow of King Henry's heir Prince Edward, who was killed by the Yorkists. He finds her at the funeral of Henry VI, whose corpse "bleed[s] afresh" at Richard's arrival (according to Renaissance tradition, the body of a murdered person would begin to bleed again if the killer came near). Lady Anne is initially livid, spitting on Richard and accusing him of having caused the deaths of both her husband and father-in-law. Richard denies the charges and begins to romantically court her, whittling away at her anger with his eloquence. He falls on his knees and offers her his sword, telling her to kill him if she will not forgive him, for he cannot live knowing she hates him. As Anne aims the sword at his chest, Richard tells her that he did indeed kill King Henry and Prince Edward, but only because he was so madly in love with her. This makes her drop the sword as Richard slips a ring onto her finger. She exits, reluctantly promising to meet him later for marriage, leaving Richard alone to celebrate with the audience.

The scene then shifts to the English court, where the established nobles are at odds with the up-jumped and ambitious Woodvilles, the family of Queen Elizabeth – this factionalism, of course, has been inflamed by Richard. As these noblemen bicker, they are interrupted by Queen Margaret, widow of the dead Henry VI, who warns them against trusting Richard. The Yorkist nobles only sneer at the Lancastrian Queen Margaret and ignore her warnings. Meanwhile, Richard sends two murderers to the Tower of London to kill Clarence. They find him sleeping and, as the murderers discuss how they will do the deed, Clarence wakes up. He pleads for his life and tells them to go to Richard, believing that his brother loves him and will reward them for letting him live. The murderers reveal that it was Richard who sent them before stabbing Clarence and dragging him off to drown him in a barrel of malmsey wine.

Richard brings news of Clarence's death to King Edward, who is on his deathbed. Richard leads Edward to believe that Clarence was killed on the king's own orders, which were not countermanded in time to save their brother's life. Edward tearfully laments Clarence's death and blames his nobles for not speaking up on Clarence's behalf. Before long, King Edward succumbs to his illness and dies. Since his son and heir, Edward V of England, is still too young to rule on his own, Richard becomes Lord Protector. With the help of his supporters – including his cousin, the Duke of Buckingham, and Sir William Catesby – he moves to consolidate his power. On the orders of Richard and Buckingham, several prominent members of Queen Elizabeth's faction are arrested, including her brother, Earl Rivers, her son, Lord Richard Grey, and her ally, Sir Thomas Vaughan. They are imprisoned in Pomfret Castle, a fortress where traitors are held and often killed. When word reaches Queen Elizabeth, she realizes that the rest of her family is in danger and goes into hiding, along with her youngest son, the Duke of York.

Synopsis: Act III

The young and uncrowned Edward V arrives in London, where he is greeted by Richard and Buckingham. The prince asks what has happened to the relatives on his mother's side, but rather than admit that he has arrested them, Richard vaguely replies that "those uncles which you want were dangerous" and calls them "false friends"; the irony of this statement is not lost on the audience, who know that Richard is the uncle that Edward should really fear. Presently, Lord Hastings arrives to announce that Queen Elizabeth has taken the young Duke of York and claimed sanctuary; according to English tradition, if a fugitive claimed sanctuary within a church or holy place, they were outside the reach of the law. Buckingham orders Hastings and a cardinal to go and fetch York and forcibly remove him from his mother if necessary. When the cardinal protests that it is sacrilegious to violate a claim of sanctuary, Buckingham retorts that a child cannot claim sanctuary, and the cardinal relents. Before long, Hastings and the cardinal return with York, and Richard coaxes Edward and York into the Tower of London, telling them they must stay there until Edward's coronation can be held.

After the princes are shut up in the Tower, Richard meets with Buckingham and Catesby to discuss their next step. They question the loyalty of other powerful lords – specifically Lord Hastings and Lord Stanley – and Catesby is sent to sound out Hastings' loyalty. He arrives at Hastings' manor in the small hours of the morning and tells him that Richard wants the crown for himself, to which a horrified Hastings responds, "I'll have this crown of mine [i.e. his head] cut from my shoulders / before I'll see the crown so foul misplaced" (3.2.43-44). Shortly thereafter, Richard holds a council at the Tower of London, ostensibly to discuss young Edward's coronation. He is initially pleasant and jovial, even asking the Bishop of Ely to send for a bowl of strawberries. But after Catesby takes him aside to tell him about Hastings' remark, his demeanor changes. He calls the lords' attention to his arm, which everyone knows has been withered since birth, and claims that Queen Elizabeth has conspired with Hastings' mistress, Shore, to cast a spell that has caused it to shrivel up. When a perplexed Hastings skeptically begins to respond, "If they have done this deed, my lord-", Richard pounces on the opportunity to brand him a traitor: "If? Thou protector of this damned strumpet, / Talk'st thou to me of ifs? Thou art a traitor, / Off with his head!" (3.4.73-76). Hastings is put to death, as are Rivers, Grey, and Vaughan, the lords being held at Pomfret.

Having purged their political opponents, Richard and his allies now have the court under their control and are able to move on to the final step of their plan. They concoct a story that the Princes in the Tower are bastards, conceived by the lustful Edward IV out of wedlock, meaning that Richard is the rightful heir to the throne. Buckingham is sent to spread this story throughout London in order to stir up support for Richard's claim. But this plan backfires when, instead of cheering, the crowds of Londoners merely stare at Buckingham in terrified silence. Although he is enraged that he does not have the people's support, Richard decides to go ahead with his plan anyway. He shuts himself up with two bishops while Buckingham and the mayor of London make a show of begging him to accept the crown, for the good of England. Richard pretends to not want the throne and tries to refuse, but is ultimately 'persuaded' to accept. Thus, Richard's coup has succeeded, and he ascends the throne as King Richard III.

Synopsis: Acts IV & V

Although he is now king, Richard III feels insecure in his new reign so long as his two nephews are alive. He asks Buckingham to kill them, but the duke hesitates. Richard, realizing that Buckingham might be too weak to continue as his right-hand man, is forced to turn to an assassin, Tyrrel, to do the deed; the assassin succeeds by having the two boys smothered. Buckingham, whose confidence in the new king is already shaken, asks Richard to fulfill an earlier promise by granting him the earldom of Hereford. Richard, however, refuses, causing Buckingham to defect and flee to his estate in Wales, where he begins to raise an army. He is later captured by Richard's men and executed. Richard is still paranoid and insecure, and decides the only way he can further legitimize his rule is by marrying Elizabeth of York, the young daughter of King Edward IV and Queen Elizabeth. To do this, he needs his wife Anne out of the way – he orders Catesby to spread a rumor that she is sick, before killing her with poison.

Meanwhile, Queen Elizabeth and the Duchess of York – Richard's mother – are grieving over the deaths of the Princes in the Tower. Queen Margaret arrives and castigates them for not listening to her warnings about Richard, telling them that all the Yorkist deaths are just payback for the deaths of her husband, Henry VI, and son, Prince Edward. Elizabeth asks Margaret how she learned to curse, and Margaret bitterly replies that she must first experience as much grief and loss as she has before exiting. Just then, Richard arrives at the head of a military procession. The Duchess of York wastes no time cursing him, shouting that she wishes she had never given birth to him before storming off, leaving Richard alone with Queen Elizabeth. Richard tells the queen of his plans to marry her daughter, and, while Elizabeth is naturally horrified, Richard once again uses his powers of persuasion to wear her down, telling her that such a marriage might be the only way to avoid civil war. Queen Elizabeth promises to discuss the matter with her daughter and exits.

Richard's commanders then bring him the dire news that the Earl of Richmond – Henry VI's nephew and a claimant to the throne – has landed in England with an army. Richard decides to offer battle and commands all loyal lords to join their forces to his. He is unsure about the loyalty of Lord Stanley, who, after all, is Richmond's stepfather; to coerce Stanley into loyalty, Richard takes his son hostage, threatening to execute him if Stanley should aid the enemy. The night before the climactic battle, Richard falls into a troubled sleep in which he is visited and cursed by the ghosts of all those he has killed. When he wakes, it seems as if he is disturbed by his conscience for the first time as he realizes how alone he really is:

Soft! I did but dream.

O coward conscience, how dost thou afflict me…

I shall despair. There is no creature loves me;

And if I die, no soul will pity me.

And wherefore should they, since that I myself

Find in myself no pity to myself?

Methought the souls of all that I had murdered

Came to my tent, and every one did threat

Tomorrow's vengeance on the head of Richard.

(5.3.179-180; 200-207)

Despite his misgivings, Richard leads his army against Richmond's the next morning, at the fateful Battle of Bosworth Field. Just as Richard has feared, Lord Stanley turns against him by joining his forces with Richmond's, but, fortunately, Richard is persuaded to wait until after the battle before executing Stanley's son. The battle turns against Richard, and his horse having been slain, he famously runs out, shouting for another: "A horse, a horse! My kingdom for a horse!" (5.4.7). He nevertheless refuses Catesby's offer of help, resolving instead to end the battle by seeking out Richmond and killing him in single combat. After fighting and killing five decoys, he succeeds in locating Richmond – the two duel, and Richard III is killed. The triumphant Richmond – soon to take the crown as King Henry VII – declares victory, announcing that he will "unite the White Rose and the Red"; by this, he means he will unite the houses of Lancaster and York by marrying Queen Elizabeth's daughter. The Wars of the Roses are over, and the new Tudor Dynasty now reigns supreme. Richmond closes the play by declaring a new era of peace for England, and entreating God not to let any more traitors like Richard cause more blood to spill:

Abate the edge of traitors, gracious Lord,

That would reduce these bloody days again

And make poor England weep in streams of blood.

Let them not live to taste this land's increase

That would with treason wound this fair land's peace.

Now civil wounds are stopped, peace lives again:

That she may long live here, God say amen.

(5.5.35-40)