The Pillow Book (Makura no Soshi) is a personalised account of life at the Japanese court by Sei Shonagon which she completed c. 1002 CE during the Heian Period. The book is full of humorous observations (okashi) written in the style of a diary, an approach known as zuihitsu-style ('rambling') of which The Pillow Book was the first and greatest example.

Sei Shonagon

Sei Shonagon was a lady of the Japanese imperial court. Her surname is not her actual name but refers to her role, or more likely the role of her husband, as a 'lesser counsellor' or shonagon. Her family name was Kiyohara, her father being Kiyohara no Motosuke (908-990 CE) who was himself a waka poet of some repute and co-author of Gosenshu, an imperial anthology. Her grandfather, Kiyohara no Fukayabu, was an even more renowned poet. Sei Shonagon was born c. 966 CE, was married at least twice and was known to have visited certain Buddhist and Shinto sacred sites and temples.

Sei Shonagon was part of a wider group of literary ladies employed to educate Teishi (976-1001 CE), one of the wives of Emperor Ichijo. Sei Shonagon joined the court in 993 CE, and she describes her early experience there as follows:

When I first went into waiting at Her Majesty's Court, so many different things embarrassed me that I could not even reckon them up and I was always on the verge of tears. As a result I tried to avoid appearing before the Empress except at night, and even then I stayed hidden behind a three-foot curtain of state. (Keene, 413)

One of Shonagon's literary rivals and lady at the second imperial court, that of Shoshi (Akiko), was Murasaki Shikibu, authoress of the classic Tale of Genji. Shikibu was scathing of Shonagon's literary skills in her own diary: "She thought herself so clever, and littered her writings with Chinese characters, but if you examined them closely, they left a great deal to be desired" (Ebrey, 199). Still, Shikibu was not above borrowing images and scenes from The Pillow Book for her own work. It is conceivable that Genji was a response to Shonagon's work given the rivalry between the two royal courts when, unusually, there were two reigning empresses.

The Pillow Book

Title & Purpose

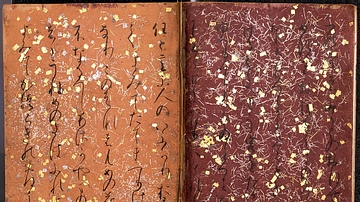

Although The Pillow Book is a highly personalised series of observations and musings on court life, where the author often employs the aesthetic technique of okashi with its objective of providing witty and surprising revelations, it does give invaluable insight into the protocols, etiquette and behaviour of the Japanese aristocracy in the Heian Period (794-1185 CE). It is written in the style known as zuihitsu meaning 'following the calligrapher's brush' or 'rambling,' and so some of the 300 plus entries are only a single sentence while others can cover a few pages. They are not presented in any particular order, and it is quite possible that later scribes reshuffled the various entries. As the author herself writes:

As a matter of fact, I wrote down, in a spirit of fun and without help from anyone else, whatever happened to suggest itself to me. (Keene, 421)

The title of the work is probably not the original one, and The Pillow Book was perhaps selected by a later scribe copying the manuscript inspired by the work's epilogue:

One day Lord Korechika, the Minister of the Centre, brought the Empress a bundle of notebooks. “What shall we do with them?” Her Majesty asked me. “The Emperor had already made arrangements for copying the Records of the Historian.”

“Let them make them into a pillow,” I said.

“Very well,” said Her Majesty. “You may have them.”

(Keene, 415)

Here the meaning of 'pillow' may be as a bedside book or private journal kept in the drawer of the wooden pillows refined ladies used. Another interpretation of 'pillow' is a poet's handbook (utamakura), and the work does often read like a list of topics meant to inspire writers and poets, presenting catalogues of plants, places, natural features, amusing human relations and so on.

Opening

The opening section of the book describes what the author considers the best times to view the four seasons:

In spring it is the dawn that is most beautiful. As the light creeps over the hills, their outlines are dyed a faint red and wisps of purplish cloud trail over them.

In summer the nights. Not only when the moon shines, but on dark nights too, as the fireflies flit to and fro, and even when it rains, how beautiful it is!

In autumn the evenings, when the glimmering sun sinks close to the edge of the hills and crows fly back to their nests in threes and fours and twos; more charming still is a file of wild geese, like specks in the distant sky. When the sun has set, one's heart is moved by the sound of the wind and the hum of the insects.

In winter the early mornings. It is beautiful indeed when snow has fallen during the night, but splendid too when the ground is white with frost; or even when there is no snow or frost, but it is simply very cold and the attendants hurry from room to room stirring up the fires and bringing charcoal, how well this fits the season's mood! But as noon approaches and the cold wears off, no one bothers to keep the braziers alight, and soon nothing remains but a pile of white ashes. (Keene, 416-417)

Example Observations

When I make myself imagine what it is like to be one of those women who live at home, faithfully serving their husbands - women who have not a single exciting prospect in life yet who believe they are perfectly happy - I am filled with scorn. (Keene, 426)

A preacher ought to be good-looking. For, if we are properly to understand his worthy sentiments, we must keep our eyes on him while he speaks. (Ebrey, 199)

In the winter, when it is very cold and one lies buried under bedclothes listening to one's lover's endearments, it is delightful to hear the booming of a temple gong, which seems to come from the bottom of a deep well. The first cry of the birds, whose beaks are still tucked under their wings, is also strange and muffled. Then one bird after another takes up the call. How pleasant it is to lie there listening as the sound becomes clearer and clearer! (Keene, 419)

A good lover will behave as elegantly at dawn as at any other time. (Ebrey, 199)

A lover who is leaving at dawn announces he has to find his fan and his paper. “I know I put them somewhere last night,” he says. Since it is pitch dark, he gropes about the room, bumping into the furniture and muttering, “Strange! Where on earth can they be?” finally he discovers the objects. He thrusts the paper into the breast of his robe with a great rustling sound; then he snaps open his fan and busily fans away with it. Only now is he ready to take his leave. What charmless behaviour! “Hateful” is an understatement. (Keene, 419)

An admirer has come on a clandestine visit, but a dog catches sight of him and starts barking. One feels like killing the beast. (Keene, 423)

One day, when the snow lay thick on the ground and it was so cold that the lattices had all been closed, I and the other ladies were sitting with Her Majesty, chatting and poking the embers in the brazier.

“Tell me, Shonagon,” said the Empress, “how is the snow on Hsiang-lu Peak?”

I told the maid to raise one of the lattices and then rolled up the blind all the way. Her Majesty smiled. (Keene, 422)

A lean, hirsute man taking a nap in the daytime. Does it occur to him what a spectacle he is making of himself? Ugly men should sleep only at night, for they cannot be seen in the dark and, besides, most people are in bed themselves. But they should get up at the crack of dawn, so that no one has to see them lying down. (Whitney Hall, 445)

I remember that once I was overcome by a great desire to go on a pilgrimage. Having made my way up the log steps, deafened by the fearful roar of the river, I hurried into my enclosure, longing to gaze upon the sacred countenance of Buddha. To my dismay I found a throng of commoners had settled themselves directly in front of me, where they were incessantly standing up, prostrating themselves, and squatting down again. They looked like so many basket-worms as they crowded together in their hideous clothes, leaving hardly an inch of space between themselves and me. I really felt like pushing them all over sideways. (Keene, 423)

Reception

The Pillow Book was already in circulation at court before Sei Shonagon had even finished it, as revealed in this passage from the final part of the book:

When the middle general of the Left was still the governor of Ise [Minamoto no Tsunefusa], he came to visit me at my home. I put out for him the mat closest to hand, only to notice to my horror that this notebook was on top. In confusion, I pulled back the mat, but he kept his grip on the notebook and took it off with him. It did not come back until a considerable time later. That, I imagine, is when it first began to circulate. (Keene, 420)

The Pillow Book was popular during the Heian Period and was much imitated, referred to in later works and quoted directly, but it was eclipsed in popularity by Tale of Genji and the 905 CE poem anthology Kokinshu over the centuries. A revival has occurred in more recent times, and the work is now widely regarded as a masterpiece of Japanese literature, the first and still finest example of the zuihitsu genre, and one of the most humorous works produced in the Japanese language.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.