Piero della Francesca (c. 1420-1492 CE) was an Italian Renaissance artist whose paintings and frescoes are characterised by their solid figures, bright colours, and harmonious composition. His masterpieces include the painted panel the Flagellation of Christ, which was created c. 1455 CE for the Ducal Palace of Urbino, and his striking portrait of his chief patron the Duke of Urbino, Federico da Montefeltro (l. 1422-82 CE). Particularly interested in perspective and proportions, Piero della Francesca would influence the work of his own pupils like Pietro Perugino (c. 1450-1523 CE) and also later Renaissance art in general.

Early Life & Style

Piero della Francesca was born in Borgo Santo Sepolcro in Tuscany, Italy around 1420 CE. His father died before he was born and so he became known as 'of Francesca', after his mother. Piero first appears in the historical record in 1430 CE when he is already the assistant of Antonio di Giovanni d'Anghiari, an artist working in San Sepolcro. The pair were commissioned to paint an altarpiece but never got around to it, and the contract was finally revoked in 1437 CE. Piero reappears again in 1439 CE when he assisted Domenico Veneziano with his (now mostly lost) frescos in Florence's San Egidio church. Despite the attractions of Florence, Piero would spend most of his working life at Arezzo and Urbino with occasional spells in Rome, Ferrara, Loreto, and Rimini.

Piero developed an ordered and austere style in his paintings where colour and perspective techniques were used to bring scenes to life. Piero was also innovative in his use of oil paints to produce frescoes. Although there were advantages of greater subtlety using oils, these were outweighed by the lack of permanence compared to the true fresco technique. The artist's interest and style in oil painting is summarised thus by The Hutchinson Encyclopedia of the Renaissance:

The oil method of [his] portraits suggests some acquaintance with Netherlandish painting but in general the art of Piero is strongly individual in its poetry and contemplative spirit, and the feeling of intellectual force conveyed by its abstract treatment of space and form. (323)

Panels, Portraits, & Frescoes

Piero produced many small panel paintings such as the c. 1450 CE Baptism of Christ now in the National Gallery, London. The c. 1472 CE panel altarpiece Madonna with the Duke of Urbino as Donor is now in the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan. A later panel is the Nativity, also in London's National Gallery. His most celebrated panel today is the Flagellation of Christ (see below), another product of his fruitful patronage by the Duke of Urbino. The artist was commissioned for portraits, too, notably for one of his patron the duke (see below) and also his second wife Battista Sforza (l. 1446-1472 CE); both of these works are now on display in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Striking works meant to be facing each other, the Battista portrait is an excellent example of a favourite technique of the artist to emphasise glinting areas of light, seen here in the translucent pearls of her necklace. In contrast, the dark shadows in the landscape behind may reflect Battista's recent and untimely death aged just 26.

Another work by the artist which captures the duke is the Triumphal Procession of Federico da Montefeltro, again now in the Uffizi. The scene is divided into two panels which are the reverse sides of the two portraits just mentioned. Dating to around 1475 CE, the double scene shows the duke with his female entourage on an elongated chariot moving to meet head-on another chariot or cart carrying Battista and her companions. The duke's passengers are personifications of the four virtues of Justice, Prudence, Strength, and Temperance. Battista's vehicle is drawn by unicorns, symbols of Chastity, while her personified passenger virtues are Faith, Charity, and (perhaps) Modesty, and Piety. Below both panels is a painted Latin inscription, which extols the virtues of the duke and duchess. In a typical nod of the grateful Renaissance artist to his patron, Federico is described as: "He that the perennial fame of virtues rightly celebrates holding the sceptre, equal to the highest dukes, the illustrious, is borne in outstanding triumph" (Paoletti, 347).

The artist's major works were frescoes, and these include the Legend of the True Cross cycle of paintings for the chapel of the Holy Cross in the San Francesco church in Arezzo. These frescoes, three large panels on each of the three walls, were worked on between 1452 and 1465 CE. They include scenes of the burial of Adam, the discovery of the cross, the return of the cross to Jerusalem, and the meeting of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, who identified the cross. The theme of the cross was especially dear to the Franciscan order, which had once been the custodian of sacred sites in the Holy Land and relics pertaining to the cross. Brightly coloured, especially in the robes of the figures and the abundant flags, the majority of the panels include somewhere an example of architecture to show off Piero's command of perspective. However, Piero has restrained his love of mathematics and allowed the narrative drama of his scenes to come to the fore. All the scenes in the cycle are connected by the artist's decision to use the actual light source in the chapel, a single Gothic window in the central wall, as the fictional light source in all of the painted panels.

Piero moved to Rome around 1459 CE and completed frescoes in the library of the Vatican. Unfortunately, and perhaps because of the artist's preference for oils, these frescoes soon deteriorated and so were replaced by new frescoes painted by Raphael (1483-1520 CE). Another fresco is the c 1465 CE Resurrection of Christ, today in the Pinacoteca of Borgo San Sepulcro (see below).

Running a successful workshop, Piero left a much more lasting legacy than his Vatican frescoes in the form of his pupils who included Luca Signorelli (d. 1523 CE), celebrated for his frescoes in Orvieto cathedral, and Pietro Perugino who continued his master's pioneering work in colour and mathematical perspective.

Art & Architecture

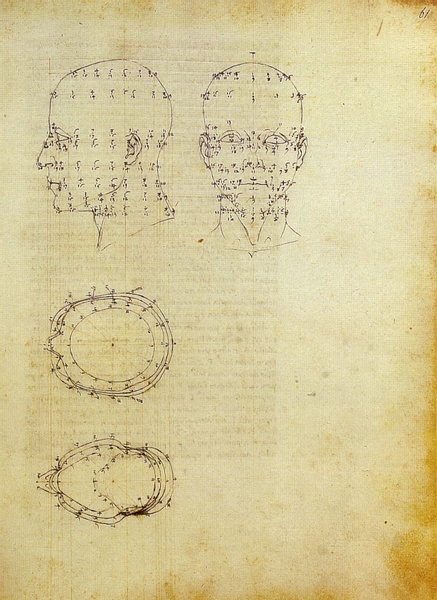

Piero studied the works of the 3rd-century BCE Alexandrian mathematician Euclid, which were then available in translation from Arabic sources. The artist was not only interested in perspective and geometry in his paintings but also in architecture, and he wrote two treatises on that subject. These are the c. 1474 CE De prospectiva pingendi (On perspective in painting) and the De quinque corporibus regularibus (On the five regular bodies). Here the artist pursued typically Renaissance ideas such as that a human head could have exactly the same mathematical rules of foreshortening applied to it as when painting a cube or designing a capital for a column. Piero, like other artists of the period, believed that the proportions of the human body were an example of perfection in nature and these proportions should, therefore, be precisely applied to architecture, both in reality and in paintings. His treatises were made more accessible, first, by being written in Italian (only later did Latin versions appear), secondly, by presenting the mathematics in such a way that uneducated artists might better understand the ideas under discussion, and thirdly, by being richly illustrated.

In addition to teaching theories, Bramante (1444-1514 CE), the famed architect who was involved in the building of Saint Peter's in Rome, was likely once a pupil of Piero. This change of focus from painting to architecture and literature was likely due to the artist's failing eyesight, something that caused him to eventually give up painting when he reached his sixties. Piero died in 1492 CE, but his work and influence on his pupils would in turn inspire such great Renaissance artists as Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519 CE), Michelangelo (1475-1564 CE), and Raphael (1483-1520 CE).

Masterpieces

Resurrection of Christ

The Resurrection of Christ fresco, which was a surprisingly rare subject matter in that period, measures around 2 x 2.25 metres (6 ft 6 in x 7 ft 4 in). Christ is shown triumphantly placing one foot on his tomb while in the foreground are a group of four sleeping soldiers. Almost nothing in the scene is what we might expect to see having read the New Testament. Christ is holding a flag, his tomb is a sarcophagus, the soldiers are not dressed in recognisable Roman attire, and the background landscape looks decidedly European. The foreshortened foreground figures and distant background of trees and hills only serve to bring the central figure more prominently to the viewer's gaze. In addition, by painting Christ full-frontal, he seems to inhabit a different space from the other figures, emphasising his other-worldliness.

Flagellation of Christ

The Flagellation of Christ is a small painted panel (82 x 52 cm / 32 x 20 in) created for the Ducal Palace of Urbino but now in the National Gallery of Marche, Urbino. While its exact subject matter has perplexed scholars, it is celebrated for its early use of perspective, achieved by the receding architecture and checkerboard flooring of the room on the left which contrasts strikingly with the frontal trio of figures on the right. The trio are difficult to positively identify and why they should be more prominent than the figures in the flagellation scene in the other half of the painting (which gives it its name, of course) is another mystery. A clue may lie in the inscription once on the painting's original frame: 'they conspired together' (convenerunt in unum). This is a quote from Psalms 2:2, and the art historian K.W. Woods, therefore, suggests that the trio of figures collectively represent humanity. She also points out that their costume suggests they each represent different professions: (left to right) a scholar, a craftsman, and a merchant. Further, the scale and proximity to the front of the picture of this trio bring the viewer into that group. Humanity, one and all, has conspired to crucify Christ and is now chatting away, blissfully unaware of the events transpiring behind them.

Mathematical studies of the painting and its proportions reveal that Piero was being very particular indeed about the position of everything in the painting. The celebrated 20th-century art historian Kenneth Clark, who did much to popularise the mysteries of fine art through television, considered the Flagellation the greatest small painting ever produced by a Western artist.

Portrait of Federico da Montefeltro

Piero della Francesca's most famous portrait is that of Federico da Montefeltro, the Duke of Urbino. Painted around 1470 CE, the portrait is an oil and tempera panel measuring 47 x 33 cm (18 x 13 in). The panel was originally set in a frame which was likely hinged to join with the portrait of Battista Sforza (the frames seen today are not the originals). The work is a strikingly close-up and (literally) warts-and-all depiction of the artist's powerful patron. Federico's splendid red clothing, hat, and rather unique nose (he had lost a part of the bridge and his right eye in a medieval tournament) are set against the contrasting green of a receding landscape which seems so far away that the duke is brought even closer before the eyes of the viewer. In another enlarging effect, the duke's collar is precisely at the line of the background horizon. The fine details of the landscape show an influence from Netherlandish painters and indicate the changes that are about to come in Renaissance art, with artists striving for ever greater realism in their work.