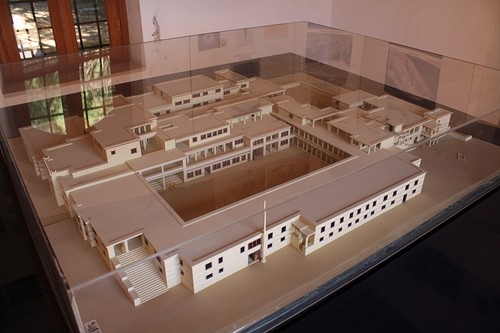

The unique contribution of the Minoan civilization to European architecture is possibly most evident in the great palace structures of the major Minoan centres of Knossos, Phaistos, Malia and Zakros. Perhaps influenced by Egypt and the Near East and evolving through the monumental tombs of the preceding period, these magnificent buildings, constructed from c. 2000 BCE to c. 1500 BCE, were so complex and ahead to such a degree of the architectural standards at that time that, at Knossos at least, they may even have been the original source of the Labyrinth myth, such would have been their effect on the casual visitor. Certainly, the palatial complex common to many sites of Minoan Crete is a unique contribution to the architectural buildings of Bronze Age Europe.

Minoan Palaces

Whilst the word 'palace' is commonly used to refer to the centres on Minoan Crete, one must be wary of such modern connotations as 'political' and 'centralised power' which the word 'palace' implies. The Bronze Age Minoan complexes were large and well-appointed, they included large public areas and had extensive storage magazines but the archaeological evidence is, at present, not sufficiently conclusive to state definitely that these palaces were the seat of a central religious/political ruler or ruling body. However, it is fair to say that the presence of a large numbers of seals, Linear A tablet archives, pithoi and amphorae and the space dedicated to storage facilities (over one-third of the site) would suggest that the palaces were the centre of some sort of centralised commerce and trade, both local and foreign. In addition, the very size and splendour of the buildings would suggest the necessity for a certain centralized planning, artisan, and materials organisation.

The striking feature of the palatial complexes is their overall size, covering several thousand square metres. Also impressive are their height; reaching four stories in some parts. Another feature was the relative smallness of the individual rooms within the palace. These rooms were often multi-functional as corridors, entrances and exits, air passages or as light-wells, another Minoan innovation. Unfortunately, the paucity of archaeological finds has made it difficult to determine the exact function of many of the rooms. For example, the small sunken rooms or 'lustral basins', which were below floor level and reached by a right-angled staircase, are much discussed as to their original function. The presence of sacred horns may suggest a ritual purpose for a specific ceremonial courtyard or chamber but more definite evidence is lacking.

Closed or opened by means of wooden doors which could be set back into recesses in the walls, the rooms of the palaces could be arranged in many different ways. This labyrinthine layout was increased perhaps by the evolutionary nature of the development of the palace, built from the centre outwards. A further effect of this was that the visitor would have had to travel through many twists and turns before finally arriving at the impressive central courtyard, the focal point of the entire complex, constructed on 2:1 proportions and oriented north-south.

Despite the seemingly random and confused structural layout of these communal buildings, it is possible to observe some degree of repetitive and organizational structure in the different palaces. East and or west wings usually contained large halls, smaller and sometimes sunken rooms were often near storage areas, which were often located in the western wing. Light-wells were usually at one side of the smaller rooms and in the centre of the longer, rectangular ones. There were always main and subsidiary entrances, and a hypostyle (colonnaded) hall in the north wing. In contrast, some features are not shared between sites, for example, the 'throne room' unique to Knossos or the circular stone pools of Zakros.

Building Materials

Materials used for construction were ashlar blocks of local sandstone and limestone with timber crossbeams and rubble added, perhaps to resist seismic activity. A large western court is also common to the palaces, and these were usually paved with limestone flagstones. Stairs, doorjambs, and in some rooms, benches, flooring (with red or white plaster in the interstices) and sometimes the lower parts of walls were also made with gypsum. Roofs were always flat and constructed with wooden beams. Decoration of a monumental building included stone carvings, particularly, horns of consecration. Walls were painted, sometimes with frescoes, stuccoed or veneered.

Colonnades & Water Systems

Large colonnaded areas with a central courtyard were also a typical Minoan feature. Tapering pillars of red or black-painted wood, usually complete and upturned trunks, often set on a stylobate and with simple black or red round wooden capitals (and also simpler stone columns) were used not only to support ceilings but to divide spaces, allow the entrance of light and air and perhaps even for aesthetic effect.

Another innovative feature of the palaces are their complex drainage systems. These took the form of stone channels, settling basins, under-floor clay pipes, and clay U-shaped tiles, often incorporating runnels and curves to slow the descent of the water and avoid splashing.

In summary, one might say that the monumental buildings or palaces of Bronze Age Minoan Crete with their colonnades, central courts, imaginative use of space and general splendour, laid the ground plan for future Aegean civilizations, in particular the Mycenaean civilization and later Greeks, who would incorporate many of these features into their own monumental architecture.