Hisham's Palace at Khirbat Al Mafjar (the ruins of Mafjar) is an Umayyad structure that is listed among the last of the surviving antiquities of Romans and Byzantines. It was built by Walid Ibn Yazid in 734 CE near Jericho in the Jordan Valley during the reign of Caliph Hisham Ibn Abdelmalik between 724-743 CE. This palace is among the last of the very sophisticated desert palaces in the region and is renowned for its elaborate mosaics, stucco carvings and overall sculptural magnificence. It is famous for the decorations that represent illustrations belonging to early Islamic classical art. It was built mostly from sandstone and baked brick.

Dimensions & Layout

The plan and location suggest it may have been a khan or guest-house. The significance of this building can be seen in various levels. The geometrical pattern of both plan and elevation creates a sense of harmony and this unity is highly emphasized in the rich décor of colorful mosaics. This design actually reflects the luxurious standard of living and the political and tribal power of the Umayyads. The structural aspects of Khirbet al-Mafjar reveal an elaborate use of vaulting system involving the dome and barrel vaults.

Khirbat Al Mafjar is a large complex measuring about 265 m and it includes three major areas consisting of a two-storied palace, a mosque accompanied by a small courtyard, a bath including an audience hall (throne room), all of which are enclosed by an outer wall. To the east, bordering the length of the site extends a forecourt with a centrally featured fountain. The main gate of the compound is centrally located on the southern façade of the palace and is flanked by two solid buttress towers on either edge of the front of the structure. However, other Umayyad desert palaces tend to conform to a single type as their central feature is an enclosure roughly 70 m. per side - a common Umayyad measurement unit based on a multiple of the Roman foot.

Like the plans of other Umayyad residences, Khirbat Al Mafjar shows some strange irregularities. For example, the axis of the porch and those of the entrance hall are not parallel, and neither are they produced westwards. These axis fall on the centre of the opposite side of the courtyard or align with the axis of the central room within. The porch itself is far from the east side. The overall plan closely resembles a square and can convince the viewer that the builders intended to make it as one.

Khirbat Al Mafjar contributes to our general understanding of early Muslim architecture. There is a genetic connection between a specific architectural feature of Khirbat Al Mafjar and of the buildings that came earlier, which can be inferred from the porches of the secular structures. The monumental projecting porch does not occur in mosque architecture until the Great Mosque of Mahdia, built about 916 CE and have long since disappeared. However, the porches at Khirbat Al Mafjar suggest that they must have existed earlier.

Palace Residential Area

The palace residential area is composed of large and small rooms facing inwards onto a courtyard. The initial impression of the plan represents the essence of a residential building, reflecting in its careful arrangement of rooms within an outer wall the most ancient Oriental concept of what a house should be - a zone enclosed within continuous walls. The house plan gives the impression that it was harem, a chamber reserved for the family.

Bath Hall

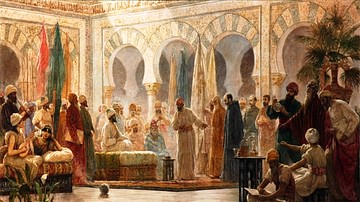

The bath hall at Khirbat Al Mafjar is the most lavishly decorated building. It is well-known to historians of Islamic art through the excavation and reconstruction of its layout by Robert Hamilton, who gives life and meaning to the different elements of its architecture and decoration. This bath hall seems to have served as an appropriate arena for the extravagant life by Al Walid II, as described by his biographers and which eventually led to his assassination. The bath complex contains one of the earliest and most famous and unique mosaic panels from the classical period of Islamic architecture representing a lion attacking a gazelle underneath a tree.

The bath or Hammam, located about 40 m north of the palace site, is the second largest building. The ruins reveal that the buiding used to be a bath as they are comprised of irregular-sized mounds with fragments of brick, carved stone and rubble scattered here and there. It appears that construction of the bath preceded that of the palace. Moreover, it is not unusual to have a bath located in a remote part of the palace as two other Umayyad baths, Hammam as Sarakh and Qusayr' Amrah were also built in an isolated area with no residential buildings located in the nearby vicinity. In the elaboration of architecture and ornament, the bath at Al Mafjar was equally, if not better, developed than the palace itself.

Mosaics

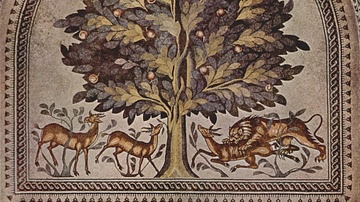

Khirbat Al Mafjar was adorned in different ways with mosaics, stucco carvings and sculptures embellishing mostly the Palace entrance hall, the bath and the audience hall. Geometrical and figural mosaics cover the floor of the bath resembling carpets and the walls are covered with fine painted stucco. The floor is covered by two mosaic panels - one rectangular with a geometric design and the other an arched panel filling the slightly elevated floor of an apse. The arched panel has the representation of the lion attacking the gazelle. It is the only mosaic panel in the complex that has a figural motif, suggesting that this motif had a symbolic meaning of particular significance. The mosaic is thought to be symbolic of the advent of peace that follows the triumph of Islam.

At the centre of the mosaic panel is a large tree bearing fruit that look like pomegrantes. The foliage of the tree seems to grow on both sides from two vertical parallel trunks connected by a smaller branch. The viewer looking into the room can see the lion attacking a gazelle underneath the tree on his right side.

In decorative terms, Umayyad palaces contain the most powerful forms of architecture and décor extending from mosaic floors to walls lined with decorated tiles and stucco. Much of the visual attraction of Umayyad architecture and its decoration is the manner in which the old forms were recombined, rejuvenated and recreated by the new culture that was endowed with immense wealth and searching for an individualistic form of art. The paintings of Khirbat Al Mafjar are also a remarkable document not only to record the existence of a tradition of painting in pre-Islamic Syria and Palestine, but also to show that there were enough monuments from earlier times in that area to provide evidence of the elements of synthesis of eastern and western styles and of a juxtaposition of older and more recent ones.