Inca architecture includes some of the most finely worked stone structures from any ancient civilization. Inca buildings were almost always practical and pleasing to the eye. They are also remarkably uniform in design with even grand imperial structures taking on a similar look to more humble buildings, the only significant differences being their much larger scale and quality of finish.

Fond of duality in many other areas, a particular feature of Inca architecture is that it typically incorporated the natural landscape yet at the same time managed to dominate it to create an often spectacular blend of geometrical and natural forms.

Materials

Stone was the material of choice and was finely worked to produce a precise arrangement of interlocking blocks in the finest buildings. The stone was of three types: Yucay limestone, green Sacsayhuaman diorite porphyry, and black andesite. Each block of stone could weigh many tons and they were quarried and shaped using nothing more than harder stones and bronze tools. Marks on the stone blocks indicate that they were mostly pounded into shape rather than cut. Blocks were moved using ropes, logs, poles, levers and ramps (tell-tale marks can still be seen on some blocks) and some stones still have nodes protruding from them or indentations which were used to help workers grip the stone. The fine cutting and setting of the blocks on site was so precise that mortar was not necessary. Finally, a finished surface was often provided using grinding stones and sand.

That rocks were roughly hewn in the quarries and then worked on again at the their final destination is clearly indicated by unfinished examples left at quarries and on various routes to building sites. The meticulous process of laying, removing, re-cutting and then re-laying blocks to make them fit exactly together was slow but experiments have demonstrated that it was much quicker than scholars had previously thought. Even so, it would have taken many months to produce a single wall. Interlocking blocks and sloping walls make Inca buildings extremely resistant, but not immune, to earthquake damage. 500 years of earthquakes have done remarkably little damage to Inca structures left in their complete state.

More humble structures used unworked field stones set with mud mortar or used bricks of dried mud (adobe) in areas with a drier climate. Both types of structure were typically covered in a layer of mud or clay plaster and then painted in bright colours. Walls at Puka Tampu, for example, still have traces of red, black, yellow and white paint.

Roofs were generally made of thatch from grasses or reeds placed on poles made of wood or cane. The poles were tied together using rope and fixed to the stone walls using stone pegs which protruded from them. These pegs could be fitted into the wall or be carved from one of the blocks, they could be circular or square, and they sometimes appear on interior walls to function as pegs, perhaps for textile wall coverings. Sometimes the top of the gable had a stone ring, again for attaching the roof. The incline of roofs was steeper in rainier parts of the empire, often 60 degrees.

Features

The vast majority of Inca buildings were rectangular and most of these had a single entrance and were composed of only one room as dividing walls are not common in Inca design. There are some rare examples of multiple-doored long rectangular structures and even buildings which were circular or U-shaped but the norm was for straight-walled structures. Most buildings had only a single storey but there are some structures with two, especially those built into hillsides and the more impressive imperial structures at the capital Cuzco where sometimes there are examples of three-storey buildings.

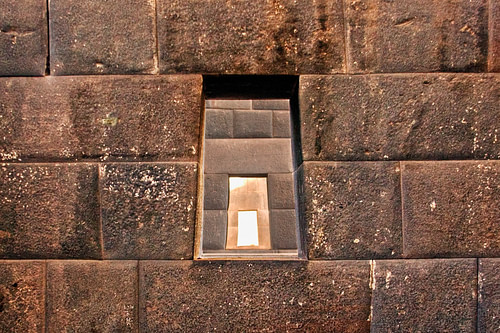

Inca exterior walls commonly slope inwards as they rise (typically around 5 degrees), giving the building a distinctive trapezoid form. The trapeziod form is more common in the north and centre of the empire and one of its optical effects is to make walls seem higher and thicker than they actually are. The trapezoid motif was repeated in doorways, windows and interior wall niches. Doorways and windows often also have double jambs and the former are usually topped with a large single stone lintel.

Architecture in the capital and the imperial buildings dotted across the empire were remarkably similar in their design to other more mundane structures. They were, of course, often much larger in scale and the quality of their stonework was much higher. They could also be more ambitious in design by employing curved walls and they could be decorated more lavishly, for example, with gold sheeting as at the sacred Coricancha precinct at Cuzco whose curved wall section survives in part today. This duality of lower and higher class buildings being the same yet different was very much a trait of the Inca culture in general.

Inca buildings may have been uniform in their basic design principles and may appear to lack individuality but the names of several architects have survived in the historical record - names like Huallpa Rimichi Inca, Inca Maricanchi, Acahuana, Sinchi Roca, and Calla Cunchuy - which suggests there was some individuality permissible in architectural design.

Structures

Rectangular buildings could be grouped in threes (or more) and arranged around an open but walled courtyard or patio, perhaps the most common Inca arrangement of buildings. This mini-complex is known as a kancha and functioned as administrative buildings, workshops, temples, accommodation or a mix of these. Very large buildings are known as a kallanka and these typically have several doors and face a large open space, often (once again) trapezoid in layout. They were probably used for public gatherings and as accommodation for representatives of the Inca administration and were clear public symbols of imperial control. Palaces were similar in design to smaller buildings just on a larger scale, with finer stonework and very often walled to restrict access and the viewing of royal personages.

Each major Inca settlement had an ushnu which symbolised imperial Inca control across the empire. The ushnu was a type of viewing platform for processions, important state-sponsored ceremonies, and judicial proceedings, and was located on one side of the principal plaza. Another feature of towns were gateways which often provided monumental entrances to towns and one of the most impressive must be the main gate of Quispiguanca with its two-storey tower and triple door jamb.

Collca (or Qollqa) were storehouses which were often built in groups or blocks. They could be round or rectangular but only had a single room. They are often situated on hillsides which gave them both good ventilation and shade, therefore, better preserving their perishable contents. Gravel under-flooring and drainage canals were additional aids in keeping the interior atmosphere dry and allowed for the storage of goods such as grain and potatoes for two years or more.

Inca settlements were rarely fortified as warfare was generally conducted via set-piece battles and the compliance of conquered peoples was ensured through political, economic and cultural means rather than military ones and imposing imperial architecture was an important part of the colonial process. However, there are exceptions. Some have seen Machu Picchu as a fortified site whilst last-stand settlements against the Spanish such as Ollantaytambo were fortified with large block terrace walls.

Hillside terracing, like buildings, used either loose rocks fixed with mud mortar or finely cut large blocks. They could extend the land available for cultivation and provide better water and drainage for crops but they were also sometimes merely decorative and planted with flowers. Those terraces at Pisac and Ollantaytambo are amongst the most impressive and their design has a definite and planned aesthetic effect.

Even rock outcrops were carved into functional forms by the Inca. For example, at Sacsayhuaman a throne-like carving with steps was cut into a stone hill. Sections of smaller rock outcrops could be cut into geometrical shapes or designs such as zig-zags and rectangles cut into the rock, their exact purpose unknown. Such works also purposely exploited the play of light and shadow to give a further geometrical dimension to the natural landscape. For example, the zig-zag walls at Sacsayhuaman create triangular shadows which seem to mirror the shadows created by the mountain peaks in the background. Rooms were also cut out of natural clefts in rock, one of the most famous being the temple shrine of the sun god Inti beneath the Torreón tower at Machu Picchu.

Setting

Town planning was an important point of consideration for Inca architects. Main roads often cut through towns at an angle, Huánuco Pampa is a good example. Entire zones of a town were built in alignment with the central plaza and its ushnu and royal residences typically faced the sunrise. More generally, the long sides of Inca buildings were usually set parallel to plazas. Blocks of buildings were never quite square and were intersected by narrow straight roads built only for pedestrians. Sometimes even the entire town had a planned form of its own, the most famous example was the intention that the layout of Cuzco should create the figure of a puma when seen from above.

Another important consideration for Inca architects was the placing of buildings, doors and windows in such a way that views were seen to their best advantage and that astronomical bodies and events - certain stars or the sun during the solstices, for example - were visible through these portals. It is rare for the portals of an Inca building not to consider the environment in which they were constructed.

On another level, Inca architects also very often sought to harmoniously blend their structures into the surrounding landscape. Perhaps the most famous example of this is Machu Picchu, which follows the contours of the hillside and even incorporates natural features such as large rocks into the actual buildings. Sometimes the outline of a sacred stone or building was even designed to mimic the contours of a natural feature such as a distant mountain. Other celebrated examples of walls seamlessly incorporating underlying rocks are the hunting lodge of Tambo Machay and the sacred fortress site of Sacsayhuaman at Cuzco. The result of this integration is a somehow harmonious blend of the organic and the geometric and a clear message was given that just as rulers can dominate a subject people, so too humanity can respect, but ultimately dominate, nature.