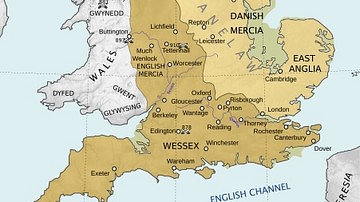

Guthlac of Crowland (c. 674 - 11 April 714 CE) was an Anglo-Saxon saint from the Kingdom of Mercia. He is best known for his years spent as a hermit in the Fens region of the East Midlands. Guthlac was born into a noble Mercian family and became a successful soldier and military leader in his teenage years before turning to religious life. He joined the monastic community at Repton in Derbyshire at the age of 24. After two years at Repton, he left to lead the life of a hermit on the island of Crowland or Croyland. During his years as a hermit, Guthlac became renowned for his holy life and for the miracles he performed.

Sources

Much of what we know of Guthlac's life comes from the Vita Sancti Guthlaci, or Life of Saint Guthlac, written by the monk Felix probably in the 730s CE. Felix's work was commissioned by King Ælfwald of East Anglia (r. 713-749 CE). In the preface to the Vita, Felix asserts that he based his work on the testimony of those who knew and spoke with the saint himself while he lived. Other important sources include the Old English poems Guthlac A and Guthlac B. These poems are contained in the Exeter Book and present the life of Guthlac in alliterative verse. While their authorship is unknown, it is clear at least that Guthlac B draws heavily from Felix's Vita. There also exists an Old English sermon and translation of Felix's work as part of the Vercelli Book, a 10th-century CE anthology of poetry and prose. Yet another source, the Guthlac Roll, tells the story of Guthlac's life in a series of 18 pictures on a scroll nearly 3 meters long.

Early Life

Guthlac was born c. 674 CE to a Mercian nobleman named Penwalh and his wife Tette in the territory of the Middle Angles. The biographer Felix tells us that Guthlac's ancestry could be traced back to Icel, one of the founding figures of the Mercian royal house. Guthlac's sister, Pega, was later venerated as a saint in her own right. According to Felix, Guthlac's birth was preceded by a divine prodigy: a human hand reached down from the heavens and touched a cross on the door to the house in which Tette was in labour. Everyone who saw this prodigy fell on their knees and prayed, taking it for a sign from God. Shortly thereafter, a servant came rushing to tell the onlookers that the child Guthlac was born. Thus the onlookers took the hand for a sign of the child's future glory.

Felix portrays Guthlac as a model child who never misbehaved or showed any disrespect to his parents or their household. When he reached his teenage years, Guthlac became a soldier, inspired by the heroic stories of his people. He gathered his own following of warriors, and for the next nine years, he fought on the Mercian borders, raided towns and villages, and collected treasure. However, Guthlac eventually grew troubled by the transitory nature of his life as a warrior. One evening, in particular, Guthlac felt extremely anxious about the course of his life. Felix writes that he "contemplated the wretched deaths and shameful ends of the ancient kings of his race in the course of the past ages, and also the fleeting riches of this world and the contemptible glory of the temporal world" (Colgrave, 81). With this in mind, he vowed to dedicate his life to Christ.

Repton Abbey

The very next day Guthlac left his home, despite the pleas of his followers to stay, and travelled to the monastery of Repton, in modern-day Derbyshire. There he received the monastic tonsure from the abbess Ælfthryth and remained for the next two years. At Repton, he lived a life of exceptional piety, never again drinking alcohol aside from communion. His brethren there at first resented him but grew to respect and even love him when he proved the sincerity of his devotion. He learned to read and write and dedicated himself to the study of scripture.

After two years of life in the monastic community, Guthlac left Repton to lead a life as an ascetic. He set out to find a proper hermitage and arrived in the swampy Fens region in modern-day Lincolnshire near the River Granta and the town of Cambridge. Here a man named Tatwine guided him to the island of Crowland, deep in the swamp. Others had tried to inhabit the island before Guthlac, but all had failed as the place was said to be haunted by phantoms and demons. Unfazed, Guthlac arrived at Crowland on the feast-day of Saint Bartholomew and vowed to spend the rest of his days there.

Crowland Hermitage

Felix describes Guthlac's preparation for the ascetic life like a soldier preparing for war, reflecting the warrior ethic of his Anglo-Saxon audience:

Girding himself with spiritual arms against the wiles of the foul foe, he took the shield of faith, the breastplate of hope, the helmet of chastity, the bow of patience, the arrows of psalmody, making himself strong for the fight. (Colgrave, 91)

He made his home on Crowland in the side of an old barrow, which Felix describes as having been previously opened by robbers in the hopes of finding buried treasure. Guthlac built a hut on this spot and, from that time on, never again wore any clothes but animal skins and never ate any food other than barley bread once a day with a cup of muddy water.

Once he had settled into his new life, Guthlac was quickly set upon by the devil with a series of temptations. First, the Devil fired a poisoned arrow of despair which "stuck fast in the very centre of the mind of the soldier of Christ" (Colgrave, 97). For three days, Guthlac languished in self-doubt, recalling the sins of his previous life and fearing that he could never be cleansed. But in the evening of the third day, he steeled himself against his anguish and called upon the Lord for aid. Shortly thereafter, Saint Bartholomew himself appeared to Guthlac and remained in his presence until he overcame his abjection. Bartholomew promised to come to his aid whenever he needed, and Guthlac's confidence in his mission was restored.

Next, two demons appeared before Guthlac in human form, complimenting his faith and steadfast resolve. They offered to teach him how to fast, reminding him of the biblical heroes and saints of old who had mastered bodily weakness. The demons urged him not to fast for only two or three days, but for seven days at a time. Guthlac saw through this false instruction and ate his daily bread defiantly, sending the demons into a fit of fury. Their angry screams could be heard far and wide before they abandoned their ruse.

Only a few nights later, Guthlac was deep in prayer when he was attacked by a horde of evil spirits who bound his limbs, carried him out of his hut, and threw him into the waters of the surrounding marsh. According to Felix, the spirits had

great heads, long necks, thin faces yellow complexions, filthy beards, shaggy ears, wild foreheads, fierce eyes, foul mouths, horses' teeth, throats vomiting flames, twisted jaws, thick lips, strident voices, singed hair, fat cheeks, pigeon breasts, scabby thighs, knotty knees, crooked legs, swollen ankles, splay feet, spreading mouths, raucous cries. (Colgrave, 103)

They dragged Guthlac through the swamp and beat him with whips before carrying him to the gates of hell itself. But Guthlac remained unshaken and challenged his tormentors to cast him into hell if that was their intention. Just as it seemed that the demons would follow through on their threats, Saint Bartholomew appeared once again and frightened off the spirits. Guthlac was then returned to his dwelling on Crowland where he resumed his holy living.

Even after the failure of this trial, spirits once again attacked Guthlac. One evening he was once again in prayer when a troop of British-speaking demons approached his dwelling. Felix writes that Guthlac understood their speech as he had spent some time among Britons prior to becoming a monk. These demons lifted him into the air on the points of their spears and carried him about. Guthlac, perceiving that his assailants were but demons, recited the first verse of Psalm 67, and the demons vanished into thin air.

Miracles Performed

Felix recounts a series of miracles performed by Guthlac before and after his death, the first of which occurred when a priest named Beccelm came to Crowland to become his servant and to learn from him. An evil spirit possessed Beccelm and drove him to take up a sword and kill Guthlac. However, the Lord granted Guthlac the gift of prophecy, and he discerned Beccelm's intentions. Guthlac then confronted Beccelm and informed the man that he was under the influence of a malign spirit. Realizing that Guthlac was right, Beccelm threw himself at his master's feet and begged his forgiveness. Guthlac not only forgave Beccelm but promised to come to his aid whenever he needed in the future.

Guthlac performed a number of miracles involving communion with animals and the finding of lost objects. He also healed the sick and knew the words and thoughts of those who were not present. His miracles made him famous throughout Mercia and beyond. He was officially ordained a priest by a bishop named Hedda, who visited with him at Crowland. He was also visited by Ecburgh, an abbess and the daughter of King Aldwulf of East Anglia (r. c. 664-713 CE). During her visit, she asked Guthlac who would inherit the hermitage at Crowland when he died. Guthlac predicted that he would be succeeded by a man who was currently a pagan but who would be baptized and find his way to Crowland. This later proved to be true as Cissa, Guthlac's immediate successor on Crowland, had not yet been baptized at this time.

Guthlac was also visited by Æthelbald, a Mercian prince driven into exile by King Coelred (r. 709-716 CE). Æthelbald arrived at Crowland exhausted from fleeing Coelred and seeking Guthlac's divine counsel. Guthlac assured him that God would grant him the kingship of Mercia in time, and it indeed came to pass. Years later, Coelred died during a banquet, and Æthelbald succeeded him as King of Mercia.

Later, Guthlac became very ill and informed his servant Beccelm that he would die in eight days. During the span of those eight days, Guthlac's hut was filled with angelic songs and sweet scents. His death is traditionally dated to 11 April 714 CE, which was thereafter celebrated as his feast day. He had previously instructed Beccelm to go and find his sister Pega and bring her back with him. When Beccelm and Pega arrived back at Crowland, they found Guthlac's body and, after commemorating him for three days, buried him there in his oratory.

Legacy & Veneration

Twelve months after Guthlac's death, Pega decided to translate his remains from Crowland to another tomb. She arrived at Crowland with a gathering of priests and high-ranking clergy to open Guthlac's sepulchre. They found his body whole and undecayed, "as if it were still alive" (Colgrave 161). Even the garments in which he had been buried showed no signs of wear or decomposition but appeared as new. This was a sure sign of Guthlac's sanctity, and all present were amazed by the miracle before them.

When Æthelbald, still an exile, heard of Guthlac's death, he grieved and visited the saint's body. Guthlac's spirit appeared to the prince and assured him that the day was near at hand when he would become King of the Mercians. Within the span of a few days, the prediction proved true, and Æthelbald was indeed crowned king. Not long after, he built a monument at Crowland to honour Guthlac's memory and, in agreement with Pega, placed the saint's remains within.

Over the course of the 8th century CE, a monastic community developed at Crowland, following in Guthlac's footsteps. Crowland Abbey was founded in 971 CE, according to the Benedictine Rule, and was dedicated to Saints Mary and Bartholomew, as well as to Guthlac himself. Guthlac was venerated as a prominent local saint ever since, with churches being dedicated to him throughout the area around the Fens in the East Midlands and beyond.