The Cyrenaics were a philosophical school of thought founded c. 4th century BCE by Aristippus of Cyrene (l. c. 435-356 BCE) who taught that sensual pleasure was the highest good and only worthwhile pursuit in life. Known as the first hedonistic school, Cyrenaicsim was eventually replaced by the more comprehensive philosophy of Epicureanism.

The school takes its name from Cyrene, North Africa (modern-day Shahhat, Libya), Aristippus' hometown, and the city where his vision was later developed by his daughter Arete of Cyrene and then formalized by her son Aristippus the Younger, credited by many scholars as the actual founder of the Cyrenaic school. His teachings produced the three best-known Cyrenaic philosophers:

- Anniceris (l. c. 300 BCE)

- Theodorus the Atheist (d. c. 250 BCE)

- Hegesias of Cyrene (the Death Persuader, l. c. 290 BCE)

The vision of the school seems to have been influenced by (or is at least similar to) that of Pyrrho of Elis (l. c. 360 to c. 270 BCE), the skeptic philosopher whose teachings were popularized by Timon of Philius (l. c. 320 to c. 235 BCE) and Sextus Empiricus (l. c. 160 to c. 210 CE). According to Pyrrhonism, one should not make judgments or offer conclusions based on sense perception because one could only be sure of one's own experience, which did not necessarily correspond to objective reality. This was also a basic tenet of the Cyrenaic school after Aristippus the Younger, and possibly of the vision of Aristippus of Cyrene, though this is unclear as everything known of the school comes from other writers and anecdotal accounts.

The Cyrenaics were eventually eclipsed by the philosophy of Epicurus (l. 341-270 BCE), who also maintained that pleasure was the principal goal of life but in a far more moderate form than that of the Cyrenaic school. Epicureanism encouraged restraint, self-control, and contentment with simple pleasures as contrasted with Aristippus' vision of pursuing whatever pleasure one found at hand as often as possible as long as one did not become addicted to the pursuit, and the more radical philosophy of later Cyrenaics such as Hegesias.

The central vision of the Cyrenaic school is summed up in Aristippus of Cyrene's line, "I possess, I am not possessed" meaning one should pursue pleasure but not allow it to enslave one. The pursuit of pleasure, in fact, was intended to encourage personal freedom in that one was not bound by the philosophical or cultural constructs of others but could follow one's own path and establish one's own vision of the meaning of life.

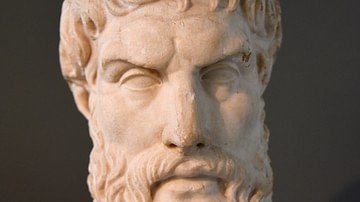

Aristippus of Cyrene

Aristippus is mentioned by Plato and Xenophon (both fellow students of Socrates), but almost all that is known of his life and teaching comes from later writers. Diogenes Laertius (l. 3rd century CE) included him in his The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, which provides anecdotal information on his life, but Laertius, infamously, failed to cite his sources or, it seems, even proofread his own text as he frequently contradicts himself and so is considered largely unreliable. Still, he continues to be cited because, sometimes, what he said can be verified from other sources and, essentially, because it is clear he was working from older sources no longer extant, even if those sources are unknown.

Aristippus was born in Cyrene and studied in Athens where he became one of Socrates' followers. After Socrates was executed in 399 BCE, Aristippus, like many of the other students, began teaching his own vision and was the first of the Socratic philosophers to charge a fee. He encouraged people to pursue pleasure as the ultimate meaning of life and, this being so, that there was no reason to feel guilty for enjoying oneself and living as one pleased. In his chapter Life of Aristippus, Laertius writes:

He was a man very quick at adapting himself to every kind of place, and time, and person, and he easily supported every change of fortune…as he always made the best of existing circumstances. For he enjoyed what was before him pleasantly, and he did not toil to procure himself the enjoyment of what was not present. (III)

On one occasion, he was reproached by Plato for living in an expensive way; and he replied, "Does not Dionysius seem to you to be a good man?" And as he said that he did; "And yet," said he, "he lives in a more expensive manner than I do, so that there is no impossibility in a person's living both expensively and well at the same time." (IV)

Aristippus' famous saying, "I possess, I am not possessed" lay at the heart of his teaching in that he felt all pleasurable pursuits were equally valid as long as one did not lose oneself to them:

On another occasion he was going into the house of a courtesan, and when one of the young men who were with him blushed, he said, "It is not the going into such a house that is bad, but the not being able to go out."

(Laertius, IV)

If one lost oneself to pleasure, Aristippus' teachings suggest, one was no longer free but had become a slave to passion, and so a detached restraint was integral to his vision: one could enjoy whatever one wanted as often as one liked as long as one could always walk away as easily as running toward. The underlying tenet of his philosophy was freedom; the pursuit of pleasure was only the physical manifestation of that freedom. Aristippus' hedonism also valued wisdom, intelligence, and personal dignity:

He was asked once in what educated men are superior to uneducated men; and answered, "Just as broken horses are superior to those that are unbroken." ... A saying of his was, "that it was better to be a beggar than an ignorant person; for that a beggar only wants money, but an ignorant person wants humanity." Once when he was abused, he was going away, and as his adversary pursued him and said, "Why are you going away?" "Because," said he, "you have a license for speaking ill; but I have another for declining to hear ill." When someone said that he always saw the philosophers at the doors of the rich men he said, "And the physicians also are always seen at the doors of their patients; but still, no one would choose for this reason to be an invalid rather than a physician."

(Laertius, IV)

Aristippus' philosophy is summarized in a passage from the Roman writer Aelian (l. c. 175 to c. 235 CE):

Aristippus, by strong arguments, advised that we should not be anxious about things past or future; arguing that not to be troubled at such things is a sign of a constant, clear spirit. He also advised to take care only for the present day, and in that day, only of the present part, wherein something was done or thought; for he said, the present only is in our power, not the past or future; the one being gone, the other uncertain whether ever it will come.

(Histories, Book 14.6)

As with much concerning Aristippus, it is unclear what work Aelian is citing here – if any. Laertius claims that Aristippus wrote many works and, in the same passage, that he wrote nothing. Later writers also seem to frequently refer to Aristippus the Younger simply as "Aristippus", and so this passage might be referencing the grandson credited with formally founding the Cyrenaic school.

Cyrenaic School & Beliefs

Aristippus of Cyrene returned to his home city in North Africa and seems to have established a school there as evidenced by later writer who reference his daughter, Arete, assuming leadership over the School of Cyrene when he died. Arete taught the philosophy of her father to her son – who was given the epithet "mother-taught" – and he eventually became head of the school, codifying the teachings of his grandfather and developing his vision.

Although Aristippus advocated for restraint and self-discipline in maintaining one's personal liberty, he seems to have leaned more toward self-indulgence than his grandson who emphasized both and the importance of a virtuous life in attaining pleasure. Cyrenaic teachings focused on epistemology (how we know what we know) and ethics (how we behave in accordance with what we know). His epistemology seems to be influenced by the skepticism of Pyrrhonism as defined by Sextus Empiricus:

Skepticism is an ability, or mental attitude, which opposes appearances to judgments in any way whatsoever, with the result that, owing to the equipollence of the objects and reasons thus opposed, we are brought firstly to a state of mental suspense and next to a state of "unperturbedness" or quietude…by "appearances" we now mean the objects of sense perception, whence we contrast them with the objects of thought or "judgment."

(Outlines, I.IV.8-10)

The Cyrenaics held to this same vision in that any judgment about external reality could only be understood as one's own experience and could not possibly apprehend that reality objectively. One's subjective experience of life differed significantly from what life might actually be, and so, the Cyrenaics believed, what one believed to be true was true to oneself but there was no way of knowing whether that belief corresponded to actual reality. Since there is no way of knowing whether one is viewing a sad play, one could not say, "This is a sad play" but only, "I am feeling sad as I watch this play."

The same would hold true for an observation of a lamp or chair. One should not presume to say, "That is a golden lamp" or "That is a red chair" because others in the room might see the lamp as yellow or copper and the chair as maroon or orange. In this, the Cyrenaic vision mirrored the philosophy of Protagoras (l. c. 485-415 BCE) who claimed "of all things, a man is the measure" in that what is true to Person A may not be true to Person B, but Person B's truth has no bearing on that of Person A. If A's truth differs from B's, both should simply accept that and refrain from argument because conflict is antithetical to the highest good and purpose in life: pleasure.

Their ethics proceeded from this understanding. Since no one can know what anyone else knows, and external reality is incapable of being grasped, one should focus one's energies on seeking pleasure for its own sake and allow others to do the same – or not – as they please. Aristippus of Cyrene (if Aelian's passage applies to him) was clearly a presentist – one who lives for the moment – and this carpe diem mindset appears in the Cyrenaic teachings – but Aristippus the Younger (or possibly Arete) softened the earlier claim and included thought for the future. Although present pleasures are not to be denied, the Cyrenaics said, one should recognize potential threats so as to avoid future pain. An example of this would be drinking to excess or smoking; both might seem pleasurable in the moment, but the long-term consequences would not be worth the indulgence.

Still, long-term planning was thought more likely to cause pain than pleasure since the future was uncertain and one's hopes far from certain. One should, therefore, choose a present pleasure over a future one as often as possible. Planning for the future in the belief that one's dreams would come true, they said, was not only a waste of time but an almost certain guarantee of disappointment and pain.

Anniceris, Theodorus & Hegesias

This philosophy was developed by the Cyrenaics who came after Aristippus the Younger. In his philosophy, friendship was a means to an end – one's own pleasure in another person's company – but Anniceris claimed that friendship could be a pleasure in itself. As one cared for one's friend, one's happiness became dependent on theirs, and so in working selflessly for their happiness, one experienced pleasure. He claimed the same for devotion to a cause or to one's country or community in that, as these prospered through one's efforts, one would be pleased, not just for one's own sake, but for another's.

Theodorus, who studied under Anniceris, rejected all the above and claimed friendship was a waste of time because such relationships make pleasure dependent upon another. To Theodorus, people sought out friends simply to satisfy their own needs but, if one were living correctly according to one's own precepts, one would not have any such needs but be self-sufficient. Theodorus also rejected the Cyrenaic claim that physical pleasure is superior to intellectual pursuits and emphasized the value of education as pleasure. He is best known for losing public arguments to the Cynic philosopher Hipparchia of Maroneia (l. c. 350-280 BCE), wife of Crates of Thebes (l. c. 360-280 BCE) as given by Diogenes Laertius. In his time, he was sharply criticized as an atheist, but his beliefs may have been more in line with the agnosticism of Protagoras, who did not deny the existence of the gods only that he was "not able to know whether they exist or do not exist, nor what they are like in form; for the factors preventing knowledge are many" (Baird, 44). Based on Theodorus' views of relationships and devotion, however, he would have most likely rejected religion as a source of pleasure.

The most dramatic departure from the teachings of the early Cyrenaic School came from Hegesias of Cyrene who maintained that pleasure is the greatest good and aim in life but is an impossible goal owing to its impermanence. No matter what pleasure one might attain, he is said to have claimed, one will lose it because of the transient nature of life, and so the wisest course is suicide. According to Hegesias, there was no more intrinsic value in being alive than in being dead, and he set his beliefs down in the book Death by Starvation in which a man who has decided to starve himself to death argues persuasively with the friends who are trying to save him that suicide is the only rational response to a life of fleeting joys and endless disappointments. The work is no longer extant but gave Hegesias his epithet of "Death Persuader" and is referenced by Laertius and by Cicero (l. 106-43 BCE) in his Tusculan Disputations, Book I.

According to Cicero, Hegesias' arguments were so convincing, he was banned from lecturing at the Library of Alexandria – or anywhere else – by Ptolemy II Philadelphus (r. 285-246 BCE):

[The subject of death] is indeed so copiously handled by Hegesias, the Cyrenaic philosopher, that he is said to have been forbidden by Ptolemy from delivering his lectures in the schools, because some who heard him made away with themselves.

(Book I.34)

Hegesias, however, did not kill himself, nor did his followers, who, according to Laertius, were known as the Hegesiaci, and taught:

The wise man would not be so much absorbed in the pursuit of what is good, as in the attempt to avoid what is bad, considering the chief good to be living free from all trouble and pain; and that this end was attained best by those who looked upon the efficient causes of pleasure as indifferent.

(Life of Aristippus; 9.92)

Hegesias, therefore, replaced the Cyrenaic goal of the pursuit of pleasure with the avoidance of pain, and since, in his belief, life itself was pain, suicide was the only sound choice.

Conclusion

The followers of these three philosophers, all calling themselves after their names, developed their beliefs further and, at the same time, argued against the teachings of Epicurus which were gaining ground. Epicurus claimed, as had Aristotle (l. 384-322 BCE), that the purpose of life was happiness (eudaimonia – to be possessed of a good spirit), which was to be lived in a state of tranquility and freedom from anxiety (ataraxia) as well as freedom from pain (aponia). One attained this state, he claimed, through enjoying simple pleasures, surrounding oneself with friends, and working at a rewarding job.

Like the Cyrenaics, Epicurus placed the greatest value on one's own subjective perception and, although he did not deny the existence of the gods, claimed they were irrelevant to human affairs as they could not be apprehended objectively. One should not, therefore, worship a deity in expectation of reward or fear of punishment but to give thanks, which would elevate one's spirit through gratitude and encourage happiness. In this elevated state, one would not fear death – which Epicurus held as a major source of anxiety – and could focus on enjoying the gifts life offered, however simple.

The Cyrenaics, especially in their splintered state, had no chance against the teachings of Epicurus, which were far more comprehensive and hopeful. The Cyrenaic school gradually lost adherents who embraced Epicureanism or Stoicism, and by the mid-3rd century BCE, it had become a memory. Its legacy lived on, however, through its contrast – and some similarities – to Epicurean thought, and writers of the 3rd century BCE and later still considered the Cyrenaics impressive enough to record their beliefs and how they had been lived.