Captain William Kidd (c. 1645-1701) was a Scottish privateer turned pirate who, despite only ever capturing one significant prize ship, has become legendary thanks to the persistent rumour he buried a fantastic treasure that nobody has yet found. Kidd was arrested, sent to England, and hanged in Wapping Old Stairs in 1701.

Captain Kidd was a most unlikely pirate given that he had received a royal commission for a privateering expedition in the Indian Ocean. Although Kidd did attack some small vessels which were not legitimate targets given the terms of his commission, his fate ultimately hung on his capture of the Quedah Merchant. A show trial in London deemed that Kidd was guilty of piracy since this ship, although perhaps sailing under a French flag, was no longer an enemy of England’s following the termination of the Nine Year’s War (Sep 1688 - Sep 1697) a few months previously. Ill luck, poor timing, and his abandonment by the publicity-shy English authorities who had backed his original mission, all ensured that Kidd was found guilty of piracy and murder. Not only was he hanged, but Kidd’s body was left to rot in public for years as a conspicuous warning to others.

Privateering in the Caribbean

Few details of William Kidd’s early life are known with any certainty. He was born c. 1645, the son of a Presbyterian minister. Traditionally, his birth town is given as Greenock in western Scotland. Kidd first began privateering in 1689 when he operated on the eastern coast of North America and the Caribbean. Privateering was the legitimate capture of ships and cargo from merchant vessels classed as enemies of a particular state. As captain of the Blessed William, Kidd attacked French ships, a legitimate target during the Nine Years’ War between France and England (and various allies). Kidd was part of the fleet that attacked Marie-Galante, one of the Guadeloupe islands, in December 1689. In February 1690, Kidd’s crew hijacked the Blessed William while their captain was ashore and sailed off for a life of piracy. Kidd, despite this setback, acquired the command of another ship, the Antigua, and he pursued the Blessed William to New York in 1691.

The Indian Ocean Expedition

Kidd settled in the Manhattan area of New York where, in May 1691, he married the wealthy widow Sarah Oort, raised two daughters, and perhaps earned a living as a respectable merchant with a bit of small-scale privateering on the side. Around 1695, he decided to try and find backing in London for more lucrative privateering expeditions further afield. Kidd sailed to London in the Antigua for this purpose. Kidd joined forces with an American entrepreneur called Robert Livingston and Richard Coote, the Earl of Belmont (or Bellomont, 1636-1701), who was a Member of Parliament and who had just been appointed the new governor of New York and Massachusetts. The trio found a group of anonymous investors in London who wished to attack ships of England’s enemy France and to plunder pirate vessels in the Indian Ocean. The consortium, which included some of the very highest-ranking officials in the British Admiralty and judiciary, fully intended to keep whatever they captured or confiscated from pirates rather than return it to the rightful owners. In short, the enterprise was both a secretive and a shady one.

Kidd’s ship for the expedition, also paid for by his sponsors, was the Adventure Galley. Purpose-built in Deptford, London, the 287-ton three-masted ship could pursue a target in all conditions thanks to its mix of square-rigged sails, lateen sail, and banks of oars (46 in total). The Adventure Galley was crewed by over 150 men and was well-armed with 34 cannons. There was one significant downside to all this financial backing, and that was that Kidd had to sign a contract which gave him and his crew only a very small proportion of any plunder taken on the expedition. At least Kidd’s privateering expedition received the legitimacy of royal support, his commission being signed by King William III of England (r. 1689-1702) who was promised 10% of the profits. Actually, there were three commissions: one to privateer against French vessels; another to apprehend pirates wherever Kidd came across them, including, if possible, the notorious Henry Every; and a third, to keep all booty for sharing amongst the investors without going through any courts as was the usual practice.

Kidd set sail from England to New York in April-May 1696 where he picked up recruits over the summer for the Adventure Galley. Unfortunately, at the last minute, half his crew was lost to a press-gang, the Royal Navy’s aggressive and obligatory recruitment method. Kidd was obliged to make up the numbers with a less-than-desirable array of cutthroats and adventurers. Recrossing the Atlantic in September 1696, Kidd sailed around the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa, to finally arrive in the Indian Ocean.

Unfortunately, Kidd was, he later testified, left frustrated in his attempt to find pirates, although just about everyone knew that Saint Mary’s Island off the northeast coast of Madagascar was a den positively bristling with pirates. By the spring of 1697, and perhaps under pressure from his less-than-respectable crew, Kidd decided to turn pirate himself. He first recruited additional crew, including slaves, at Madagascar and on Johanna Island (aka Anjouan Island), now part of the Comoro Islands group. A good number of his original crew had by now succumbed to tropical diseases, and their replacements were an even more villainous group.

Kidd set about attacking legitimate merchant vessels of several nationalities, including Dutch, British, and Portuguese ships. The easiest targets were pilgrim fleets sailing from India to Mecca. Some of the larger merchant vessels and convoys proved to have too much firepower for the Adventure Galley to take on and Kidd had to settle for small ships. Through August and September, Kidd roamed the western coast of India, attacked an English trader and then the Laccadive islands where a number of the locals were robbed, beaten, and raped. Captain Kidd now looked decidedly like the commander of a pirate crew and not a privateering ship of the British Crown. One agent in the port of Carwar (now Karwar), India gives the following description of Captain Kidd at this time:

…a very lusty man, fighting with his men on any occasion, often calling for his pistols and threatening any one that durst speaking anything contrary to his mind to knock out their brains, causing them to dread him.

(quoted in Cordingly, 1996, p180).

With the lack of success in finding really rich pickings, Kidd’s motley crew proved increasingly unruly and, on 30 October 1697, perhaps to quell a possible mutiny or simply in rage at a slur on his captaincy, he killed one of his gunners, William Moore, allegedly striking him down with a wooden bucket. The mutinous atmosphere was likely over the crew wishing to try their luck at attacking the richer but better-armed British East India ships in the area. For the moment, Kidd kept command, and a moderate success came in November off the coast of India with the capture of the Rouparelle, a Dutch vessel carrying a French pass and flag. Kidd, maintaining a crew on the Adventure Galley, himself sailed the Rouparelle after renaming it the November.

Pirate or Privateer?

Into 1698, a few small vessels were then plundered, and then the big prize Kidd had been hoping for finally crossed his bow. This was the 400-ton Quedah Merchant, which was under lease to the Indian government but carrying a pass from the French East India Company. Kidd captured the ship on 30 January 1698 off the coast of India near Cochin (now Kochi). A quantity of the cargo of silk, calico, sugar, iron, and opium was sold for 10,000 pounds (around $2.5 million today). Kidd even took over the vessel and renamed his new ship the Adventure Prize. Unbeknown to Kidd, the Nine Years’ War had ended the previous September and so technically, his attack on the Quedah Merchant was not an episode of privateering but one of piracy. However, to further muddy the legal issue, the Quedah Merchant was captained by an Englishman, was an Armenian ship, and its cargo belonged to the Indian noble Makhlis Khan of the Mughal court. Khan ensured the Indian authorities in Surat put pressure on the British East India Company to make up for the loss, occupying the Company’s premises and halting trading in the meantime. In addition, and as was the custom, the ship likely held several passes issued by several national bodies and had only produced the French passport because Kidd had himself been flying a French flag when he approached the vessel.

Kidd’s ill-defined status as privateer or pirate was not helped by his attacking a Portuguese vessel and then (unsuccessfully) two East India Company ships in the spring of 1698. Kidd then seriously prejudiced his future case by swearing loyalty to the British pirate Robert Culliford (active 1690-98) on Saint Mary’s Island. Culliford had sailed with Kidd during his privateering days in the Caribbean, but if Kidd had fulfilled his commission, he should have taken Culliford prisoner. By now, the Adventure Galley’s beams were badly rotted, and the ship was abandoned. The Adventure Galley may be one of two possible pirate ship wrecks explored in the area from 1999, but the evidence is inconclusive. Hearing that a general pardon on pirates had been issued, Kidd decided it was time to return home to his wife and daughters.

Arrest

Captain Kidd sailed across the Atlantic to Anguilla in the Caribbean in April 1699, where he learnt that although there was indeed a general pardon out for pirates, all British colonial governors had been issued with a demand to arrest Kidd on sight. Kidd tried to find refuge on the Danish-controlled island of Saint Thomas but was refused entry. His only chance now was to either return to a life of piracy or sail to Boston, where he hoped his associate, governor Coote, would issue a pardon for his acts of piracy. Kidd sold off some of his cargo and exchanged his ship for a sloop, the Saint Antonio, in a pirate haven on Hispaniola. He then set sail for North America. Kidd was to be sorely disappointed again when he landed on Long Island in June as Coote, responding to a request from Kidd’s backers in London to treat him as a pirate, fully intended to respect the official call for the pirate's arrest. The investors were shocked at Kidd’s turn to blatant piracy, but it was really the formal complaint sent by the British East India Company to the British government that Kidd should be detained that made it politically impossible for Coote and his investors to publicly support their renegade employee. Accordingly, Coote arrested Kidd in July 1699, and in April 1700, Captain Kidd was sent back to England for trial. The wily Coote had managed to clear his name from his association with Kidd, and he had acquired a good portion of the pirates’ treasure to boot.

Captain Kidd’s Treasure

It may be that before he landed in Boston, Kidd had taken the precaution of burying his ill-gotten loot, with New Jersey, Long Island, and the neighbouring Gardiners Island all being possible locations. Kidd did indeed bury some of his treasure, and these locations were, under pressure, revealed to the Boston authorities. Kidd was also obliged to list in detail his booty in a document which survives today. Listed amongst the goods retrieved by the authorities are silver ingots, gold coins, jewels, bales of silk, and tons of iron and sugar. However, a persistent legend grew that Kidd had not revealed all and somewhere there was another cache of loot, perhaps much greater than that which had been recovered. This tantalizing legend has led to treasure hunters digging holes across the centuries in any possible location even remotely connected to Captain Kidd, none with any success. Speculation as to the treasure’s whereabouts has ranged from the east coast of America to India. The only tangible result of Kidd’s habit of burying treasure is that it has become a staple part of fictional pirate tales ever since.

Arrest & Trial

Captain Kidd first had to endure almost a year in the terrible Newgate Prison in London before his ultimate fate was decided. Opponents of the government tried to get Kidd to reveal who his anonymous backers were and so he was twice called before Parliament in March 1701. However, the investors, the Admiralty, and the government, all keen to disguise their unsavoury interest in privateering, closed ranks, key documents were conveniently lost - notably the French passes of the Quedah Merchant and Rouparelle - and the whole investigation was hushed up and abandoned. Captain Kidd was, nevertheless, to be made an example of to other would-be pirates. His show trial concentrated not on the intended privateering side of the Indian Ocean expedition but on Kidd’s obvious turn to piracy and the murder of his gunner (the more serious charge under English law).

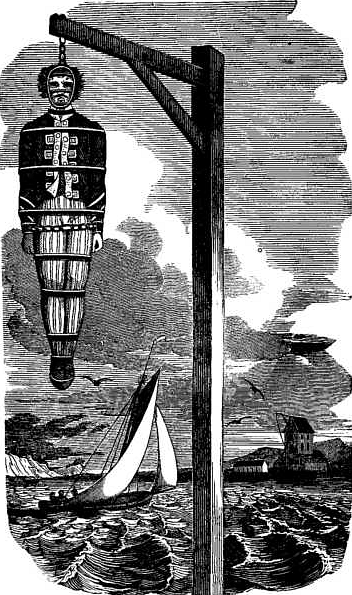

Kidd protested his innocence regarding piracy, stated that the attacks on smaller ships had been forced upon him by his rebellious crew, and noted that the two attacks on the larger vessels had been carried out in good faith as they both flew the flag of France. He also maintained he had killed Moore accidentally. Kidd was found guilty of all charges by a jury of 12 and hanged at Wapping Old Stairs on 23 May 1701. Kidd then did his posthumous reputation no good at all when he arrived drunk at his execution and launched into an unrepentant and blasphemous speech at the onlookers. Drama then turned to black comedy when the rope snapped and Kidd fell to the muddy ground still very much alive. A second noose was applied and the deadly deed done. One of Kidd’s crew, Darby Mullins, was also found guilty and hanged. Captain Kidd’s corpse was then tarred and hung in a cage to rot by the Thames as a further deterrent to pirates. The gruesome process of deterioration, largely reserved for the most notorious pirate captains, could take two years or more. Rather than deter pirates, Kidd’s terrible fate only made them more determined to fight to the death rather than be taken alive by the authorities. Indeed, Kidd became a byword amongst cutthroats for what lay in store for the captured pirate.

The Captain Kidd of Fiction

Captain Kidd became the victim of character assassination in posthumous fictional works. Certainly no saint and indeed guilty of piracy, Kidd’s career was greatly exaggerated, beginning with the rumours sent out by the squabbling political parties in England during his trial. There was a very popular ballad, Captain Kidd’s Farewell, which circulated shortly after his hanging and which recounted unspeakable but entirely undocumented deeds.

Captain Kidd was the subject of a biography alongside many other pirates in the celebrated work, the General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, compiled in the 1720s. The work was credited to a Captain Charles Johnson on its title page, but this is perhaps a pseudonym of Daniel Defoe (1660-1731), although scholars are still debating the issue and Charles Johnson may have been a real, if entirely unknown pirate expert. Johnson's/Defoe’s treatment of Kidd is less sensational than some of his other pirate portraits, but it certainly cemented him as one of the darker figures of what became known as the Golden Age of Piracy. Later writers like Washington Irving (1783-1859) only added to the spicy cocktail of cruel and barbarous pirate who refused to tell anyone where his treasure was buried that Kidd had become. There was even a musical play in 1830, Captain Kyd, the Wizard of the Sea by J. S. Jones which was popular for years in theatres in Boston and New York. Hollywood perpetuated the myth with films like 1945's Captain Kidd starring Charles Laughton, who gives a memorable turn as a cool and calculating pirate utterly ruled by greed. The fact remains, however, that Captain Kidd has gained more fame thanks to his sensational trial and mythical treasure than for any acts of piracy.