The toga was an item of clothing worn by men who were citizens of Rome. The toga consisted of a single length of wool cloth cut in a semicircle and wrapped around the body of the wearer without any fastenings. The Roman toga was a clearly identifiable status symbol.

While most togas were white, some indicated a person's rank or specific role in the community. These different togas were coloured or included a stripe, notably the purple one which indicated the wearer was a member of the Roman Senate. The toga has, thanks to film and literature, become the quintessential male garment of antiquity but the view is not far wrong as even the Romans themselves described themselves as the togati or 'people of the toga.'

What were the Origins of the Toga?

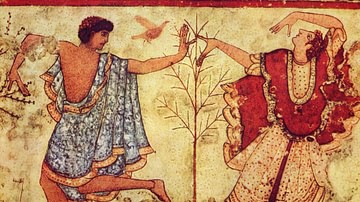

As in many other facets of their culture, the Romans were influenced by their predecessors the Greeks and the Etruscans. Greek men and women wore draped clothing which was made of a single piece of cloth wrapped around the wearer and held in place using only folds and the minimal use of pins and ties. The Greek enkyklon was a toga-like garment, but it was not given the social significance the Romans added to their toga. The Etruscan tebenna was another forerunner of the Roman toga, although it was shorter and wrapped much more simply with a fold going over the shoulder and hanging down the front of the wearer (as indicated by tomb paintings dated to the 6th century BCE and 5th-century BCE bronze statuettes). The toga seems not to have had a social distinction in Etruscan society and even lowly musicians are seen wearing them in tomb paintings. Finally, the Romans themselves had an early version of the toga, the similar but shorter trabea which was associated with the early Roman kings.

Toga Material & Dimensions

The earliest togas were the shortest, some examples measuring around 3.5 metres in length. By the imperial period, togas were an impressive 5.5 metres in length and 2.75 metres at its widest point (19.5 x 10 ft). The essential cut never changed which was always a semicircular shape, although of varying depth over time. As ever with clothing, the rich could afford to wear the finest material and the greatest length while poorer citizens had to make do with a shorter version of less-worked material. Most togas were made from light, untreated wool with the finished garment then brushed and shorn to give it a smooth nap. The Oxford Classical Dictionary gives the following instructions for putting on a toga correctly:

One corner was placed before the feet and the straight edge was taken up and over the left shoulder, across the back and under or over the right arm, across the chest, and over the left shoulder again, the second corner hanging behind the knees; the curved edge became the garment's hem. By the imperial period, two features had developed which helped to accommodate the garment's increased size: an umbo or 'navel' at the waist, resulting from the upper part of the under layer being pulled over the second layer, and a sinus or 'lap', created by folding down the straight edge where it passed under the right arm. In the 3rd century CE the umbo was generally folded into a band lying across the wearer's chest, and in the 4th century, the sinus was usually long enough to be thrown over the left forearm. (1488)

Perhaps not surprisingly, given the complexities of putting on a toga correctly and the cost of material of an ever-expanding garment, the toga went out of fashion by Late Antiquity to be replaced by the much more practical combination of tunic and mantle, which would remain popular throughout the Middle Ages.

Why Was the Toga a Status Symbol?

The toga was not worn all of the time but it did come to be associated with life in the towns and cities because it was especially important at any public events like games, rituals, and weddings. When richer citizens visited their country estates or seaside villas, though, they often wore more casual robes. In addition to this divide between town and country, those senators who were also military commanders, preferred their armour during times of war so that both of these habits made the toga a symbol of both civic life and peaceful times. Such was the ubiquitous nature of the toga that it even lent its name to a form of Roman theatre, the togata or 'drama in toga' which was a type of comedy, often based around the everyday happenings of a typical Roman household.

Not only was the toga itself a status symbol but even how it was worn became a mark of a person's distinction and familiarity with the fashion of the moment. The long cloth, as noted above, was not easy to wrap correctly around the body - becoming more complex as time wore on - and this evolution in fashion has been a useful way for historians to date pieces of Roman art. Like a necktie today, the proper arrangement of a toga's folds could clearly show a person's attention to detail and refinement. Certainly, an attendant slave with toga skills was desirable to help achieve the required effect and achieve little tricks like making a few pockets out of some of the folds. Further, because the garment was heavy and restrictive - the left arm had to be always bent to carry the weight - the continued smartness of the wearer and maintenance of the proper folds throughout the day indicated that the wearer was a man of leisure and so a true aristocrat. Besides these more subtle indicators of class, there were rather more obvious ways to display one's rank and privilege, for example, the use of colour.

What were the Different Types of Toga?

The toga, then, could be used to differentiate different citizen roles and even their achievements. One of the symbols of a young man's progress to full citizenship was the right to wear the plain toga, the toga virilis. Meanwhile, the toga candida of political candidates was bleached using sulphur to make it much whiter than the usual cream version. From candida we have the modern word 'candid' as these candidates were meant to be honest and true. Going to the other extreme, the toga pulla was dyed a dark colour and worn during periods of mourning. The most striking of all of the togas was the toga picta. Dyed all-purple and given gold trim, it was reserved only for generals when they celebrated a Roman triumph and, in the later imperial period, emperors.

The toga that most Roman males coveted, though, was the toga praetexta which had a purple stripe. This toga indicated that the wearer was a senator, magistrate or had a special ritual status, for example, they were a priest or someone charged with tending a shrine. When priests were performing a sacrifice they pulled up the back of their toga to cover their heads (capite velato). The Flamen Dialis, high priest of Jupiter, was obliged to wear his toga and a white conical cap whenever he appeared out of doors. Another category permitted to wear the coveted purple trim was young men who were not full adults but showed great promise in military or political affairs.

The stripe of the toga praetexta was known as the latus clavus and it was considered capable of averting evil. The stripe, like the all-purple toga picta, was made using the fabulously expensive Tyrian purple die which was laboriously extracted from the murex shellfish. According to the historian B. Caseau, "10,000 shellfish would produce 1 gram of dyestuff, and that would only dye the hem of a garment in a deep colour" (Bagnall, 5673). Literally worth more than its weight in gold, a 301 CE price edict informs us that one pound of purple dye then cost 150,000 denarii or around 3 pounds of gold.

Finally, and somewhat bizarrely, prostitutes sometimes wore a version of the toga praetexta, (dyed using a cheap substitute for Tyrian purple), perhaps in an attempt to titillate their clients by reversing Roman society's dress conventions. A famous depiction of the toga praetexta in more mundane action is a 1st-century CE wall painting from the Murecine building of Pompeii, which shows a procession of magistrates all wearing their purple-trim togas. Another important record of the garment is a small painted terracotta statuette of an overweight official, also from Pompeii.