The Battle of Bentonville (19-21 March 1865) was among the last major battles of the American Civil War (1861-1865). Having cut swathes of destruction first through Georgia, then through South Carolina, Union Major General William Tecumseh Sherman next invaded North Carolina, with the goal of pushing up into Virginia to join forces with Ulysses S. Grant's army outside Richmond. The Confederates hastily stitched together an army to oppose him, which was placed under the command of General Joseph E. Johnston. This campaign culminated at Bentonville, where the rebel army was defeated and forced to retreat. A little over a month later, Johnston would surrender to Sherman at Bennett Place.

Background: 'To Fight Longer Is Madness'

On the night of 15 November 1864, the city of Atlanta, Georgia, went up in flames. By morning, a full third of the city lay in smoldering ruins as 62,000 Union soldiers marched out of Atlanta and into the heart of Georgia, to begin what would become known as Sherman's March to the Sea. Led by Major General William Tecumseh Sherman, the Union army advanced in two columns, pillaging the Georgian countryside while simultaneously destroying factories, ripping up railroads, and liberating thousands of slaves. Since the main Confederate army in the region, the Army of Tennessee, was off conducting a desperate invasion of its namesake state – which would culminate in the army's destruction at the Battle of Nashville – the Confederates could offer little resistance as Sherman's troops tore through Georgia, leaving a path of destruction in their wake. On 21 December, the coastal city of Savannah fell to the Union troops, and Sherman sent off a triumphant telegram to US President Abraham Lincoln: "I beg to present you, as a Christmas gift, the city of Savannah, with 150 heavy guns and plenty of ammunition" (quoted in Foote, 712).

But although he had accomplished his objective, Sherman was not yet finished. Indeed, his gaze turned northward to the troublesome state of South Carolina. The first state to have seceded from the Union in December 1860, South Carolina was blamed by Sherman and his men for having started the war, a debt they were eager to pay with interest. "The truth is," Sherman reported to his superiors in Washington, "the whole army is burning with an insatiable desire to wreak vengeance upon South Carolina. I almost tremble at her fate" (quoted in McPherson, 826). So, on 1 February 1865, Sherman marched out of Savannah with 60,000 men up into the vulnerable underbelly of the Palmetto State. Like they had done in Georgia, his men conducted a campaign of scorched earth, but this time, they were much more thorough in their destruction. "In Georgia, few houses were burned," wrote one Union officer. "Here, few escaped". Indeed, this campaign of fire and fury climaxed on 17 February, when the state capital of Columbia was captured and subsequently burned. While Sherman did not intentionally burn Columbia, his officers did not do much to restrain their men from pillaging and burning. By the next morning, two-thirds of Columbia had been destroyed.

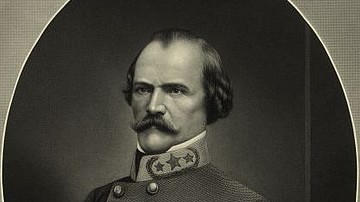

Sherman's rapid march through first Georgia and now South Carolina both terrorized and disheartened the Confederate population. "All is gloom, despondency, and inactivity," wrote one South Carolinian after the fall of the state capital. "Our army is demoralized, and the people panic stricken…to fight longer seems to be madness" (quoted in McPherson, 827). Continuing to fight against such overwhelming odds may well have been madness, but Confederate President Jefferson Davis was determined to fight, nonetheless. As the iron vices of Union Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant clamped down on the Confederate capital of Richmond, Davis tasked General Joseph E. Johnston with scraping together an army with which to defend the Carolinas. Throughout the course of the war, Davis and Johnston had rarely seen eye to eye – indeed, the president had fired Johnston from an important command as recently as July – but every other Confederate general with the needed level of experience and esteem was either preoccupied, incapacitated, or dead. So, on 22 February 1865, Johnston officially took command of all Confederate forces in the Carolinas. Most of these soldiers were the survivors of the disastrous incursion into Tennessee, while others were garrison troops pulled from Charleston. In all, Johnston had around 20,000 men to oppose Sherman's 60,000.

Sherman Invades North Carolina

Sherman did not stop after the occupation of Columbia. Instead, he pressed north, planning to march through North Carolina and up into Virginia, where he would join forces with Grant. Together, they would defeat General Robert E. Lee and his besieged Army of Northern Virginia, capture Richmond, and finally put an end to the war. Aware that Johnston had strung together an army to snip at his heels, Sherman made several feints as he entered North Carolina to keep the enemy guessing at his intended target. By mid-March, however, it had become clear that he was headed for the road junction at Goldsboro, North Carolina, and that his army was marching in two separate columns: a right column, under Major General Oliver O. Howard, and a left column under Major General Henry W. Slocum. About a dozen miles (20 km) separated the two Union columns from one another. Johnston knew that his only chance to succeed was to attack and destroy each of these columns in isolation, before they could link back up and overwhelm him.

Johnston decided to target Slocum's column first. On 15 March, he sent Lieutenant General William J. Hardee's corps on ahead to delay Slocum's advance while the rest of his army moved into position to defend the roads between Goldsboro and Raleigh. Hardee's corps – consisting of two infantry divisions of 3,000 men each – formed a defensive line at Averasboro, a town about 30 miles (48 km) south of Raleigh. Hardee's right flank was anchored by the Cape Fear River, his left by the Black River swamps, making it difficult for him to be outflanked. That afternoon, the Union cavalry screen under Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick ran into Hardee's infantrymen; after a bit of skirmishing, Kilpatrick withdrew to inform Slocum of the strong Confederate position to his front. Slocum sent two of his own infantry divisions ahead, which spent the night preparing to assault the rebel lines. At dawn on 16 March, the Union divisions attacked. The Battle of Averasboro continued throughout the day, as Hardee's men successfully held back multiple Union charges. As the day progressed, however, Slocum kept pouring more men onto the field, putting more pressure on the rebel line. Finally, at 8:30 p.m., Hardee figured that he had delayed the Yankees long enough and withdrew to rejoin the main army. The action had cost 682 Union casualties and approximately 860 rebel losses.

Preparations

On 17 March – St. Patrick's Day – Slocum continued his advance up the turnpike. Incessant rains drenched his men to the bone and churned the roads to ankle-deep mud, creating miserable marching conditions that one officer referred to as "among the most wearisome of the campaign" (quoted in Foote, 828). By now, Slocum's column was about a full day's march away from Howard's, the two wings separated by miles of shoddy backroads. This situation could hardly have been more favorable to Johnston, whose cavalry scouts informed him of the dispositions of the divided Union army. If he could strike Slocum's column with his full force and wipe it out before Howard's column could arrive in support, then he might have a chance at fulfilling his mission and saving North Carolina. On 18 March, Johnston decided to concentrate his entire army at the town of Bentonville, between Averasboro and Goldsboro.

That night, the first elements of the Confederate army reached Bentonville. The rebel cavalry, under Lieutenant General Wade Hampton III, rode out to skirmish with Slocum's column and slow it down, to give the infantry soldiers time to get into position. By midmorning on 19 March, they had successfully formed a battle line about two miles (3.2 km) south of the town. Major General Robert Hoke's division, on loan from the Army of Northern Virginia, was deployed on the left wing along the road, while the embattled veterans of the old Army of Tennessee, under Lieutenant General Alexander P. Stewart, were posted on the right, screened by a dense cluster of oak trees. The plan was for Hoke's men to pin the Yankees down with withering fire, at which point the Union troops would be flanked by Stewart's Tennessee veterans and by Hardee's corps, charging out from the brush. But the problem was that Hardee was not there yet. Relying on old, faulty maps, Hardee had gotten lost and, by the time darkness fell on the 18th, he was still six miles (10 km) away from Bentonville. Wanting to give his men some sleep before the next day's battle, Hardee opted to set up camp here. He notified Johnston that he would get off to an early start at 3 a.m., so that he could make it to the battlefield on time.

First Day: 19 March

On the morning of 19 March, a Union division under Brigadier General William Carlin was marching at the head of Slocum's column. As Carlin's division approached Bentonville, the tree line to its front came alive with the thunderous crack of rifle fire and the earth-shaking roar of artillery. Taken by surprise, Carlin's men wavered and fell back, but soon rallied after the next Union division, under Brigadier General James D. Morgan, marched up in support. Carlin and Morgan moved south of the road and formed a defensive line, trading volleys with Hoke's graybacks, lightly entrenched on the other side of the road. Throughout the morning, the battle devolved into a stalemate, since the rebels could not spring their trap without Hardee's corps. Indeed, Hardee's men had once again been slowed down by narrow roads and dense thickets and did not arrive on the field until close to noon. By then, Hoke's division had been absorbing the brunt of the Federal fire, and Johnston was urging Hardee to attack before the Confederate left flank crumbled.

Hardee sent one of his two divisions to bolster Hoke's troops on the left flank and moved around to the right with the other. At 3 p.m., Hardee launched the assault – Stewart's grizzled Army of Tennessee veterans and Hardee's own men surged forward, shoulder to shoulder, the shrill rebel yell emanating from their throats. The Federals had been fully occupied by Hoke's men to their front and were taken off guard when Hardee's screaming soldiers burst from the brush and slammed into their left flank. The Union left quickly collapsed beneath the pressure, as the rebels overran their field hospital and nearly captured General Carlin himself. The Yankees only retreated a few hundred yards, however, before they regrouped and formed a new defensive line at the Morris Farm and poured sheets of hot lead into the faces of the oncoming Confederates. For a while, vicious, close-quarters fighting took place along this point before the rebels were forced to pull back, leaving their wounded behind to groan and writhe in pain as their lifeblood flowed out of them.

In the quick lull that followed, a third Union division arrived to shore up Carlin's and Morgan's defenses – by now, each side had committed some 15,000 troops into the fray. As the setting sun lengthened the shadows over the green North Carolinian field, so too did these new Yankee reinforcements lengthen the odds against the ragged Confederate force. But Hardee was undaunted and, at 5 p.m., ordered a new attack against the strengthened Federal line. Unfortunately for Hardee, his attack was disjointed, as each of the rebel divisions got off to a different start, and they were repulsed one by one. The Union troops, now firmly dug in, yielded no ground and instead fired volley after volley into the advancing gray lines. "The assaults were repeated over and over again until a late hour," Slocum would report, "each assault finding us better prepared for resistance" (quoted in Foote, 832). Indeed, the battle raged on well into the night. It was not until around midnight, when the final Confederate assault broke beneath the light of the moon, that Hardee finally decided to call it quits. He ordered his men to pull back to their original lines, where they began to dig in and prepare for another day of fighting.

Second & Third Days: 20 & 21 March

The morning of 20 March was quiet, the peace disturbed only by the occasional clatter of rifle fire or the rumbling boom of a cannon, as skirmishes broke out across the opposing lines. Not much happened until the late afternoon, when Howard's column arrived – having received Slocum's calls for help the night before, Howard's men had marched all night and throughout the morning to get to the battle on time. Sherman, who had been travelling with Howard's men, was now personally on the field as well and spent the remaining daylight hours organizing his troops into a strong battle line extending toward Mill Creek. By the day's end, the entire Union army of 60,000 men was on the field, against the less than 20,000 Confederate soldiers. Having lost the initiative, Johnston decided not to attack; now, his only chance at success was to hope that Sherman would launch a reckless attack against his entrenched positions.

Sherman, meanwhile, expected that Johnston would retreat in the night. When the sun rose on 21 March, he was pleasantly surprised to find that the Confederate army was still entrenched in the same positions as the day before, giving him an excellent opportunity to destroy it. The main attack of the day, however, was not delivered by Sherman but by one of his division commanders, Major General Joseph Mower. A 36-year-old career soldier from Vermont, Mower had recently been praised by Sherman as "the boldest young soldier we have," and was determined to live up to that mantle (quoted in Foote, 834). Noting a weak spot in the Confederate lines in front of Mill Creek Bridge, Mower took the initiative and attacked with two brigades. Mower's men punched through the Confederate line and advanced about a mile when he was struck by a rebel counterattack. He sent a message to Sherman asking for reinforcements, confident that with a little support, he could break the rebel army here and now. What he got in reply was a stern order from Sherman, ordering him to pull back to his original position. Mower complied, having dealt a good deal of damage to the Confederate position. Among the rebel casualties was Hardee's 16-year-old son Willie, who had been mortally wounded and would die in agony three days later.

Aftermath

And so, as Mower dutifully pulled back his soldiers, the Battle of Bentonville came to an end. The Confederates had lost 2,600 casualties, including 239 killed, 1,694 wounded, and 673 missing, while the Union army had suffered 1,527 losses, including 194 killed, 1,112 wounded, and 221 missing. On the evening of 21 March, Johnston ordered his army to withdraw, burning the Mill Creek Bridge behind them. The Union army failed to pursue, as Sherman was unaware that Johnston was retreating until the next morning, by which time the rebels were already miles away. Ignoring the weakened Confederate army, which no longer posed much of a threat, Sherman continued on to Goldsboro, where he rested and resupplied his men in preparation for the final leg of his march into Virginia. But this would prove unnecessary. On 3 April, the Confederate capital of Richmond fell to Union forces and, several days later, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House. The war was effectively over, leaving Johnston with little choice but to negotiate a surrender of his own. On 18 April 1865, he signed an armistice with Sherman at Bennett House and, on 26 April, formally surrendered, agreeing to terms similar to the ones Lee had been given by Grant. The Battle of Bentonville, therefore, was one of the final major battles of the American Civil War, a desperate last gasp of the dying Confederacy.