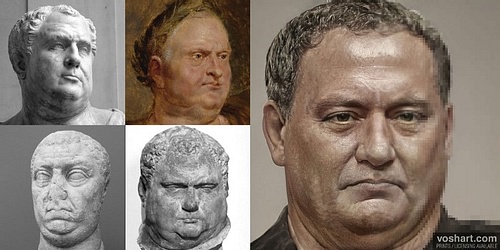

The emperor Aulus Vitellius (r. 69 CE) had never wanted to be Rome's emperor. Aulus was from a family of court flatterers to the first Caesars, and when his friend Nero (r. 54-68 CE) was dead, and there were no more Caesars to succeed, he was the last man that anyone would have expected to take the throne.

His grandfather, uncle, father and brother were powerful imperial servants on the Palatine Hill – but no more than that. Publius, the first courtier of the family, was a middle-ranking administrator, whose two sons rose higher, Lucius Vitellius becoming one of the highest officials in Rome at a time when the power of bureaucrats was new and little understood.

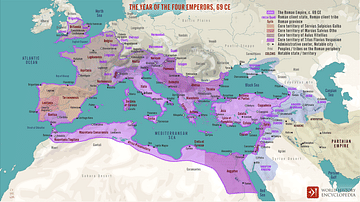

Aulus was the least of the Vitellii, promoted to a military command only because his notorious lethargy and greed made him a threat to no one. His fame was a glutton even in an age when gluttony was a regular rebuke, his lethargy such that Nero's successor, Roman emperor Galba (r. 68-69 CE), had no fear he would be disloyal. But his soldiers had liked a fellow eater and drinker and, when they won the battle against Galba's successor that brought him to power, it did not matter that Aulus was hundreds of miles away. It was a dizzying time – commanders barely mattered; only troops mattered. In the summer of 69 CE, Aulus Vitellius was being carried towards Rome in triumph – just like the seafood he so prized.

March Back to Rome

Fish from the northern coasts had always to travel alive in wooden barrels of saltwater, heavy cargoes requiring carriages capable of dragging artillery to war. It was a trade whose profits depended on assessing faraway demand. A red mullet from Marseille might be worth a small fortune one day and nothing the next. A scorpion fish, washed up on the rocky beaches of Germany where Aulus's uncle Publius had once barely avoided a mass drowning of his own troops, could find a high price as long as it was where men were competing to feed an emperor. So could prawns from the most prized Greek islands, anchovies from the Black Sea, the sea-urchins of Egypt and the oysters of Britain, sometimes rushed to market by teams of runners if the boats and trucks were too slow. However exaggerated some of the stories of Aulus's gluttony became, there seems little doubt that his victory was good for the exotic fish trade.

At first, there was little cause for a party. The roads near the battlefield showed fresher signs of savagery than the battlefield itself. The victors had begun a neighbourhood riot of plunder and destruction. The defeated too, the troops of the short-lived emperor Otho (69 CE), had joined in. For the families farming beside the Po, or fishing coarse carp or catfish in its streams, the aftermath was more brutal than the fighting. The wiser tradesmen kept their distance. The victorious armies were like an inland sea, controlled by no one but the distant tides. Only the returning commanders, with Aulus Vitellius newly at their head, restored some order. His brother, Lucius, was already Aulus's fiercest defender. Their armies swarmed, unopposed, upon the capital, a gastronomic march on Rome.

The most efficient way of cooking for successful troops on a march was to roast meat. As far back as the epics of Homer, this was the lesson. Roasting needed the fewest dishes and plates. It was not a lesson that the Vitellii brothers intended to apply. Chefs accompanied the soldiers as though they were the cavalry protecting their flanks. The troops ate well off the summer lands, their officers from the wagons from distant seas. The standard fare may have been little more than Pisa Vitelliana, the eponymous paste of peas or beans, pepper, ginger, lovage, hard-boiled yolks and honey. The only memory for later writers was of vastly expensive food, regularly demanded, imported and consumed by Vitellius, sometimes four times a day. The finest food for the march was garlanded like the most successful general, wreathed in laurel like a conquering hero. The feasting was a form of reward for his flatterers, a substitute for the real power he had not yet achieved, and perhaps an obliterating therapy for himself.

Preparation for a Triumphal Feast

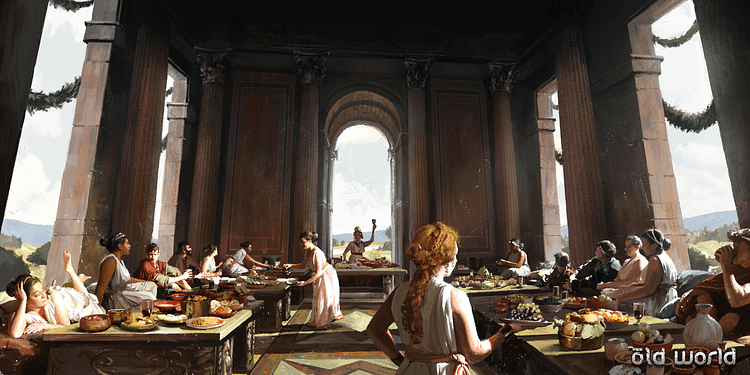

Lucius went ahead to begin preparation for his brother's cena adventica, the banquet that would mark Aulus's arrival in his capital. The finest fish needed the finest plate. No pottery dish could be made that was large enough. Silver was the favoured metal from which the rich should eat, mined in Spain, hammered and riveted into giant dishes decorated with what they were made to contain. On a gleaming dish of epic name and proportions, would lie the produce of everywhere from Parthia, still unconquered, to the Pillars of Hercules between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, still passed only by the few. Aulus and his new court would dine off Spanish silver on pikes' livers streaked in red and yellow, sperm of lampreys, brains of pheasant and peacock, tongues of flamingos.

Much lesser food would be served to thousands of soldiers and citizens, roasts and fish stew. Not everyone could celebrate with silver on the delicacies that showed Rome's reach beyond the Euphrates and the Ocean. But every rich variety, more like vomit to later minds, would become a metaphor for wider ills.

The final progress to the dining tables was as slow as Aulus's exit from Cologne. Some of the German troops, who had never seen Rome before, rushed ahead to see for themselves the Palatine. The narrow streets were awkward for the new arrivals. They found Romans as bemused by their long swords and leather jackets as they themselves were surprised at the massed white togas of officials for the new reign.

Aulus Vitellius had to make his own choice of dress. He had options. His first thought was to wear the red cloak of a conquering general, to ride on a great horse with a conqueror's sword. The theatre of war was beginning to suit him. But, well advised, Aulus Vitellius passed through the city walls on foot. He wore the toga that he had been entitled to wear while Nero was alive. His height made him easy to see, but his modesty was on view too.

Meanwhile, Lucius was preparing his banquet. Sea creatures, so far from their home seas and so freshly dead, sprawled over the largest silver plate that Lucius could find. Light was able to pass through the piles of raw flesh, tiny shrimps and slices of mullet and turbot, showing the shadows of animals, vegetables, gods and heroes carved below. The plate was called the Shield of Minerva, the protective armour for Rome's goddess of art and memory. This was not a shield for war. Those who were served from this shield would be unlikely to see even a scene of war, nothing more violent than the sword of a swordfish or the backward-pointing teeth of a pike.

Neither Lucius nor Aulus had fought themselves to advance the name of Vitellius to barely below that of the Caesars. But when Lucius gathered the roes of rare fish alongside the tongues of rare birds and spread it all over a giant piece of theatrical armour, he ensured how his brother's arrival in Rome would always be remembered. Nothing else in Aulus's reign outdid its beginning. By the winter there was a fourth emperor in a single year, 69 CE. Aulus Vitellius was falling into oblivion for everything except greed. A new emperor, Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE), was planning a fresh start, free from courtiers and bureaucrats, but less free than he hoped. Aulus himself was tumbling down into the Forum, dying slowly by blows and cuts from a new emperor's soldiers, his body slashed into fat fleshy pieces.