The crossbow was introduced into Chinese warfare during the Warring States period (481-221 BCE). Developing over the centuries into a more powerful and accurate weapon, the crossbow also came in versions light enough to be fired with one hand, some could fire multiple arrows, and there evolved a heavier artillery model which could be mounted on a rotating and movable base. The crossbow was a major factor in the success of the Chinese states against foreign armies and in establishing the dominance of the Han and Sung empires, in particular.

Design & Use

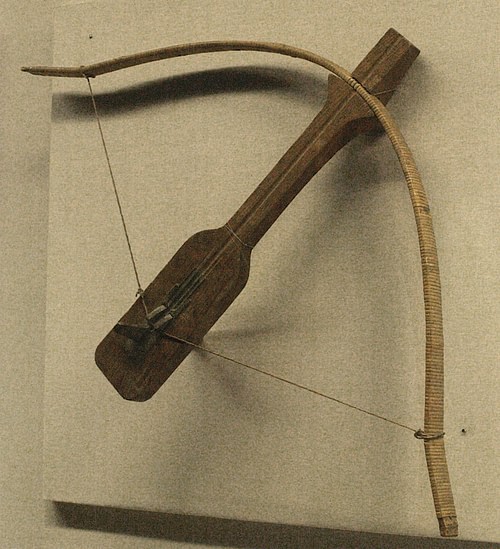

The Chinese crossbow (nu) with its horizontal bow and short wooden stock fired single or multiple bronze-headed arrows. The arrows had wooden shafts and feathered, wooden or paper vanes for stability in their trajectory. Early arrow heads had two blades but these developed over time and three blades became the norm, matching the number of vanes and increasing the accuracy of the flight. The trigger and firing mechanism was made of metal, usually bronze.

To set the crossbow for firing it was at first necessary for the shooter to place the weapon vertically and brace it under the feet while the cord was pulled back. Eventually, a belt hook device was invented which allowed the firer to draw back the cord while still mounted on his horse. There were smaller types that could be fired using only one hand - even capable of firing two arrows at once - and much heavier versions which were used as artillery weapons. The first crossbows could only fire an arrow about 600 paces and were slow to reload, limiting their effective use to defence and siege warfare. With adjustments in design, they improved and could then fire significantly further than a mounted archer.

Historical Development

Traditionally, the Chinese crossbow was first invented by Ch'in Shih of the Chu state sometime in the 6th century BCE. Early examples made only of wood would have long since disappeared from the archaeological record but the first recorded use of crossbows in Chinese warfare is at the 341 BCE Battle of Ma Ling between the Qi and Wei states. The Qi leader Sun Pin put them to good use and routed the enemy. The armies of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (771-256 BCE) were particularly renowned for their elite units armed with crossbows. Trained over seven years and wearing armour, they were said to be able to march 160 km (100 miles) without rest. It became a general belief in military treatises of the period that a good crossbowman was worth 100 infantry soldiers. The 5th-3rd century BCE military treatise Six Secret Teachings by T'ai Kung notes that an ideal army's proportions should be 10,000 infantry, 6,000 crossbowmen, 2,000 men with halberds and shields, and another 2,000 with spears and shields.

The Han dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE) used the crossbow to such good effect that it was largely credited as the reason for that state's dominance. A well-trained crossbow corps was more than capable of seeing off a cavalry charge or incurring devastating casualties if firing as a unit into the flank of enemy infantry during an ambush. Catching enemy troops in a crossfire by splitting one's crossbowmen into two groups was another highly successful tactic. The Han used both light and heavy crossbows. Crossbowmen could be mounted troops when they might also arm themselves with a halberd. There is also some evidence that a small version of the weapon existed which could be fired using only one hand. There is a story that in 203 BCE Hsiang Yu managed to conceal a crossbow and fire it at and wound the future emperor Kao-ti, suggesting that such small weapons were not uncommon.

That the weapon was first used by the richer element of Chinese society is indicated by some of the surviving metal pieces which are often intricately worked, sometimes even with gold or silver inlay. Still, by the Han dynasty, the scale of production had greatly increased. One inventory of the arsenal at the Han city of Luoyang in 13 BCE reveals that there were 11,181 crossbows and 34,625 arrows there.

During the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE) the crossbow, although still used by small units protecting the infantry's flanks, became less popular and the composite bow seems to have been the weapon of choice, as the historian C.J.Peers here comments on:

An 11th century writer remarks that the T'ang had so little confidence in the crossbow that they equipped its users with halberds for self-defence. They then tended to succumb to the temptation to throw down their crossbows and charge, so that other men had to be sent to follow them and pick up the discarded weapons. One source gives the ratio of bows to crossbows in the ideal army as five to one. (118)

By the Sung Dynasty (960-1279 CE), weapons took another step forward in design with a 1073 CE directorate of weapons given the task of supervising their production. The period saw the arrival of the repeating crossbow which was capable of firing a bolt every couple of seconds, albeit with a reduced accuracy. Other design improvements included greater firing power, the addition of sights to increase accuracy, and stirrups to aid in cocking the weapon. The crossbow's continued importance to warfare is illustrated in the following quote from the 1044 CE Wu Ching Tsung Yao which states that the crossbow is, "the strongest weapon of China, and what the four kinds of barbarian most fear" (Peers, 130). There then follows a description of its use, stating that warriors fired from behind their shields and then moved behind the infantry lines so that they were protected while reloading their weapons. A unit of crossbowmen could also advance in a circular formation which allowed them to rotate their fire and protect their colleagues while they reloaded.

Artillery Crossbows

A heavier and larger type of crossbow was developed which could be used as an artillery weapon. As well as firing single or multiple bolts from fixed positions, such crossbows could be mounted on chariots and wagons to quickly move them to where they were most needed on the battlefield. During the Warring States period siege warfare was a frequent occurrence, with well-fortified cities protected by high walls and towers. Mounted crossbows with pulleys and windlasses to draw back the cord, thus, became a useful defensive weapon.

The Han army employed a heavy crossbow which required 159 kg (350 lb.) to cock. They were mounted on a revolving base and those men strong enough to work them were known as chueh chang. The Sung also used artillery crossbows with fixed mounts and winches, but these were not as common as single-armed stone slingers which were employed in their hundreds in single battles and sieges.

Impact on Warfare

The crossbow was a technical weapon which required know-how both for its construction and effective use, two factors which gave the Chinese states a distinct advantage over their less developed neighbours. Then when the states were fighting each other, the weapon would have been particularly effective against opponent's chariots which were slow-moving on unfavourable terrain and protected only by leather coverings. One official letter describing a victory notes that "wherever the crossbow bolts reached, the chariot tracks were chaotic and the banners were scattered" (in Di Cosmo, 163). This may have been one factor in the demise of the chariot in Chinese warfare from the mid-Han period (others were the arrival of cavalry and lighter-armed, more mobile infantry forces).

As the weapon became more common armies began to equip themselves with better armour and helmets as a consequence of the crossbow's improved penetration power compared to the bow. Metal (bronze and then, later iron) or leather strips were tied together with cords and helmets fashioned from metal so as to offer better protection, although, at close range, there was not much that could stop a well-aimed crossbow bolt.

The crossbow made killing a little less personal, too. The Sung period, for example, saw the specialisation of crossbowmen with the use of snipers aiming at specific long-range targets. One success is recorded at the 1004 CE battle of Shan-chou where the general Hsiao T'a-lin was struck down by a crossbow arrow fired from afar. The increased firing range the crossbow gave meant that an army could attack the enemy despite natural obstacles that would have hitherto blocked an engagement, again allowing warfare to be conducted at a safer distance. As the military tactician T'ai Kung notes in his Six Secret Teachings: "Strong crossbows and long weapons are the means by which to fight across water" (Sawyer, 1993, 70). The crossbow was such an efficient weapon that, despite new developments such as stone slingers and gunpowder cannons, it would remain a feature of Chinese warfare well into the 19th century CE.