William Still (1819-1902) was an African American abolitionist known as the "Father of the Underground Railroad" for his efforts in helping to free between 600 to 800 people from slavery. Born the son of formerly enslaved parents, Still devoted his life to the cause of civil rights and liberty for all in the United States.

As a member of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society/Vigilant Association of Philadelphia (which he was later chairman of), Still helped orchestrate escapes, organized assistance for fugitives once they arrived in Pennsylvania, welcomed them to his home, hid them, and paid for their passage north to Boston, New York, or Canada.

He kept careful records of every freedom seeker who passed through his house in the hope these could be used to reunite them with their families someday, but also as written testimony to their courage and the efforts of the abolitionists. These were published as The Underground Railroad Records (1872), a significant primary document on slavery in the United States, those who escaped, where they came from, and where they traveled to.

After the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, abolishing slavery, rendering the Underground Railroad no longer necessary, Still continued his work in civil rights, supported various causes financially, helped desegregate public transportation in his city, and established the first YMCA for African Americans in Philadelphia. In the 2019 Hollywood film Harriet, on the life of Harriet Tubman, Still is ably portrayed by Leslie Odom Jr. and is recognized today as one of the leading figures in the struggle against slavery and a great American hero.

Family & Early Life

William Still's parents, Levin and Sidney (later known as Charity) Steel, were slaves in Caroline County, Maryland. Levin purchased his freedom in 1798 and established a home in New Jersey. Sidney tried to follow him with their four children, but they were caught. She tried again in 1806, taking only her two daughters, and escaped, reuniting with Levin, but had to leave behind their two sons, Levin Jr. and Peter.

In New Jersey, they changed the family name to "Still" in honor of friends of that name in Burlington County. To further mask her identity, Sidney changed her name to Charity. The Stills would have 18 children; William was the youngest, born on 7 October 1819. Although born in a free state, all these children were technically slaves because their mother was a fugitive slave.

William grew up hearing his parents talk about their lives as slaves and the two boys they had to leave behind. According to scholar Nick Sacco, his parents' stories, the knowledge that he was legally regarded as a slave, even though free, as well as an event in his childhood, directed Still toward the abolitionist movement:

Still also experienced the horrors of slavery as a youth in New Jersey. According to biographer James Boyd, in one instance, slave hunters arrived at a neighboring farm to capture a free Black farmer whom they claimed was an enslaved runaway. While a White Quaker named Thomas Wilkins fought off the assailants, Still and a brother-in-law helped the man travel twenty miles away to Egg Harbor on the Jersey shore. These harrowing experiences, combined with a love for reading and writing, inspired Still to take an active part in the abolitionist movement to eradicate slavery from the United States.

(33)

In 1844, Still moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and, in 1847, he was working as a clerk for the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery. He married Letitia George, and the couple would have four children. Their home became a center for the Underground Railroad and the first stop of hundreds of fugitive slaves on their way to freedom further north.

Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of free Blacks, White and Black abolitionists, Mexicans, Native Americans, and others who devoted themselves to helping enslaved people reach freedom. Operating between circa 1780 and 1865, the Underground Railroad is thought to have brought around 500,000 people from slavery to freedom.

The best-known escapes orchestrated or assisted by the Underground Railroad were those on the so-called Northern Routes, taking freedom seekers from Philadelphia to Boston, New York, and Canada, but there were operators in the South as well who assisted fugitives in reaching Mexico or Indian Territory, beyond the legal reach of slave-catchers.

The concept of a 'railroad' and 'routes' implies a set course on established tracks, but this was not so. Conductors on the 'railroad' chose whatever path suited them best and, in some cases, might not even be aware of a safe house in a given area. On the Western Routes, abolitionist John Brown (1800-1859) ran safe houses and was well known among conductors, but there were many others who were not.

There were also plenty of enslaved people who took freedom for themselves without any recourse to the Underground Railroad in any of its directions, such as Wallace Turnage (circa 1846 to 1916) in 1864. While the American Civil War was raging and Mobile, Alabama, was fortified with Confederate troops, Turnage walked 25 miles (40 km) away from slavery to freedom at the Union Fort Powell.

The Northern Routes are the most famous, at least in part, because of well-known participants including Harriet Tubman (circa 1822-1913), Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879), Passmore Williamson (1822-1895), William Still, and others. Some of the best-known freedom seekers have also made the Northern Routes more famous than others, including Ellen and William Craft (authors of Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom), Henry Box Brown, Lear Green, Clarissa Davis, and Anna Maria Weems.

Still & the Railroad

The Underground Railroad styled itself on an actual railroad and used terminology associated with the railways:

- Agents – people who alerted the enslaved to the railroad and set up meetings with conductors

- Conductors – people who guided the freedom seekers to safe houses and destinations north

- Station Masters – those who operated the safe houses and hid freedom seekers

- Stockholders – those who provided financial support for the organization

At one time or another, William Still held all these positions. He organized escapes as an agent, conducted fugitives to safe houses in Philadelphia, ran a safe house himself, and, as a successful businessman, supported the operations financially. He also involved himself directly in freeing slaves who were brought by their masters into the free state of Pennsylvania, where, by law, they could claim their freedom, as he did in the famous case of Jane Johnson.

Jane Johnson

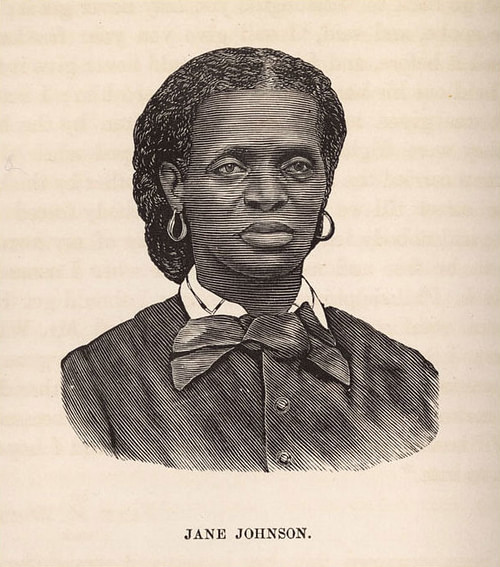

Jane Johnson (circa 1814/1827-1872) was a domestic slave of one John Hill Wheeler of North Carolina, a planter and politician. In 1855, Wheeler was given a government position in Nicaragua and was passing through Philadelphia on his way to New York to ship out. He brought his family as well as his slave Jane and her two young sons, Daniel and Isaiah.

On 18 July 1855, Jane told the Black porter at the Philadelphia hotel where they were staying that she wanted to escape, but this seemed impossible because Wheeler, knowing that a slave could claim their freedom in the city, had locked her and her children in their room. The porter sent word to Still, who, with Passmore Williamson, monitored the situation, and when Wheeler and his party were about to leave from the docks, confronted him.

While five Black dockworkers restrained Wheeler, Still explained to Jane her legal rights in Philadelphia and asked if she would like to choose freedom. When she gave her assent, Still took her and her children from the docks by carriage, first stashing them in a safe house in the city and, later, bringing them secretly to his home.

Wheeler demanded his 'property' back, and Williamson was taken to court, where he was told to produce Jane and her children. Williamson could not have done so, even if he had wanted, because he had no idea where Still had taken them. Williamson was sentenced to 90 days in jail for contempt of court.

On 29 August 1855, Still and the five dockworkers were tried for assault and causing riot, both charges brought by Wheeler. By this time, Jane Johnson and her boys had been sent safely along the 'railroad' to New York. When she heard that Still and the five dockhands were on trial, however, she risked re-enslavement and returned to testify in their defense.

The prosecution had argued that Still had taken Johnson against her will, but she made clear that she had requested assistance and had participated freely in her emancipation. She had been planning to escape from slavery with her boys once she reached New York, she told the court, but, finding opportunity in Philadelphia, she had taken it. Still and three of the dockworkers were acquitted while the other two were convicted of assault, fined, and jailed for a week.

The imprisonment of Passmore Williamson and trial of William Still focused national attention on slavery, further galvanizing anti-slavery sentiment in the North, which had been gaining momentum since the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required ordinary citizens of free states, and any government officials, to help capture and return freedom seekers. Many people objected to this policy and were already resisting it. The Jane Johnson incident and the treatment of Williamson and Still encouraged further Northern resistance.

Although Wheeler, with the help of federal marshals, tried to recapture Johnson, the Underground Railroad was able to get her out of the city and back up North, where she finally settled in Boston. After the trial, Still went back to doing what he had always done: helping those who sought their personal liberty to find it.

Underground Railroad Records

As noted, William Still kept careful records of freedom seekers who came through his home or who had been helped by others in Philadelphia. At one point, a former slave named Peter Freedman came to the city hoping to find his parents. Peter had recently purchased his freedom in Alabama and was on his way north, but he had been told there was a Black man in Philadelphia, one Dr. James Bias, he could trust for help. Dr. Bias was not at home when Peter called, but his wife suggested that he go see William Still, who was known to have extensive records on fugitive slaves and their families.

Mrs. Bias provided Peter with a guide to Still's house, and, as usual, Still interviewed him. He learned that Peter and his brother Levin had been sold down south decades ago, and that Peter's parents' names were Levin and Sidney. As Peter continued talking about his youth and parents, Still understood and said, "Suppose I should tell you that I am your brother?"

Levin Jr. had been beaten to death by his master for visiting his wife without permission, but Peter had managed to survive slavery in Alabama, purchase his freedom, and come north. He was soon reunited with their mother. In this case, of course, Still recognized the man, but in other cases, his records were available to bring about these same kinds of reunions.

At one point, fearing the records could be seized and used to locate former slaves, Still burned some of them, but, it seems, either he had copies or remembered the details because he was able to reproduce them in his 1872 work The Underground Railroad Records. Scholar Kate Clifford Larson writes:

William Still kept a record of most of the freedom seekers who sought shelter and aid through his office at the Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia. Still noted each person's name, age, height, and skin color, the name of their enslaver, where they had lived, and sometimes the runaway's personal family information, such as number of brothers and sisters and names of parents, spouses, and children. He recorded any aliases the runaways chose, ensuring that they could be found by friends and family in the future. On occasion, he took testimony from the former slaves, recording their experiences under slavery, their reasons for taking flight, and their opinions of their masters. Still also maintained detailed accounts of funds spent on each freedom seeker who came through the society's office.

(115)

Since 1872, these records have been used by people to reunite with their families or, later, locate and learn about their ancestors, how they escaped slavery, and where they went afterwards.

Conclusion

During the American Civil War, Still worked to support Black troops and ran the post exchange at Camp William Penn while still serving the Underground Railroad's cause. After the war and the abolition of slavery, he continued to devote himself to the same, establishing the first YMCA in Philadelphia for African Americans and funding programs for Black youth. He died of heart disease on 14 July 1902 at his home.

Still's legacy is widely recognized today, and he continues to be honored for his humility, courage, and self-sacrifice in the interests of others. Scholar Andrew K. Diemer notes:

In 1872, Still published his monumental account of this work, The Underground Railroad, almost 800 pages recounting the stories of hundreds of fugitives he helped on their way north. For those looking to recover Still's actions, this book has sometimes proven frustrating; Still is by no means the center of attention. In fact, for pages at a time, it can be difficult to find Still's hand at all. This absence is by design. Still understood, and wanted his readers to understand, that fugitive slaves themselves were the engine of the Underground Railroad. Here, too, the contrast with his ally Tubman is useful. Tubman's story can sometimes leave the impression that enslaved people were in need of a savior, someone to rescue them from bondage. Still's work, on the other hand, shows us that enslaved people were prepared to save themselves – they simply needed a hand.

(8)

Still was always ready to offer that hand and, between circa 1847 and 1865, helped hundreds of enslaved people to freedom, paid their passage, found them homes and jobs, reunited families, and offered his own home as a welcoming shelter. He worked closely with Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and William Lloyd Garrison, all as well-known today as they were in the 19th century; but William Still, usually working quietly in the background, and far less famous, kept the Underground Railroad running north until there was no longer a need for it.