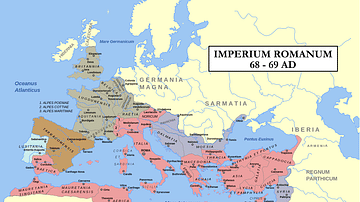

The Roman army consisted of three separate divisions: the famed legions, the cavalry, and lastly, the auxiliaries. The auxiliaries (auxilia) were comprised of infantry cohorts, mounted infantry, and cavalry units or wings (alae). Although the legions were considered the backbone of the army, the cavalry which included the auxilia became the 'eyes and ears' of the army.

Before the Romans engaged in any battle, the auxilia were used for locating potential campsites and sources of food and water as well as assessing the terrain. Along manning the frontier with the legions, the auxilia, among other duties, were used for patrolling and containing raids. According to Conor Whatley in his An Introduction to the Roman Military, the auxilia "offered fighting capabilities not provided by the legions which allowed Rome to face a wide range of threats." (87)

Origins

The army of the Roman Republic relied on civilian troops recruited from the propertied citizenry who served unpaid in the legions for the duration of the war. They were assisted by a contingency of cavalry who were led by their own commanders and supplied their own horses. As Rome conquered and expanded, change came with the reforms of the consul Gaius Marius (c. 157-86 BCE). The Marian reforms simplified requirements for enlistment and the Roman legionary was provided with all essential equipment: weapons, armor, and clothing. According to historian Patricia Southern's The Roman Army, a clause in Roman treaties required the allies to furnish troops in the time of war. These allied units or contingents became known as alae sociorum or the "wings of the allies" (239). Although each unit was commanded by a local magistrate, the overall commander was a Roman equestrian.

Upon assuming the throne, Emperor Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE) saw the need for change and completely restructured the military. This reorganization included the auxiliaries. Historian Nic Fields illustrates the effects of the changes in his book Roman Auxiliary Cavalry when he wrote that the "cavalry was given regular status similar to that of the infantry." He added that they were trained to the same standards of discipline as the legions and "were considered long-service professionals like the legionaries and served in units that were equally permanent" (4). Besides a promise of regular pay and supplies, the auxiliaries also received a plan for discharge and retirement.

In another significant change, Augustus required both the infantry and the cavalry to swear an oath of loyalty (ius iurandum / sacramentum) to the Roman emperor, not the Roman Senate or people of Rome. In this oath of allegiance, which was renewed every year on January 3, the individual swore to obey the emperor's commands and be ready to sacrifice his life for the Roman Empire.

Allied Horsemen

With the army having become professional and permanent, soldiers were needed to fill the legions and auxiliaries. The necessary manpower to fill the ranks of the auxilia came from the Roman allies in the provinces, the non-citizen peregrini (the term met foreigners or people who were not Romans). To entice these non-citizens to join the military, they were promised Roman citizenship, along with their families, after serving a 25-year commitment. Field wrote that many peregrini within the auxiliaries were drawn from people who had been former enemies of Rome and who were "nurtured in the saddle" and were recruited from the "fringe of the empire" (6) These old adversaries – the Gauls (who were considered the most skilled), Celtiberians, Germans, and Thracians – were all known for their horse-riding skills. And, as in other areas of the military, the Romans borrowed or adopted both equipment and tactics from these former enemies. These new recruits provided a "fighting arm in which the Romans themselves were not so adept" (ibid).

The historian Tacitus (c. 56 to c. 118 CE) in his Annals wrote of the Roman commander Gnaeus Corbulo's Parthian campaign in 63 CE:

Corbulo having discharged all who were old and in ill-health, sought to supply these places, and levies were held in Galatia and Cappadocia, and to these were added a legion from Germany with its auxiliary and light infantry. (Annals 13.35)

Although these horsemen came already skilled, they were nevertheless trained and disciplined in the Roman tradition. After being integrated into the cavalry, they were used for policing, combatting skirmishes, reconnaissance, and communication.

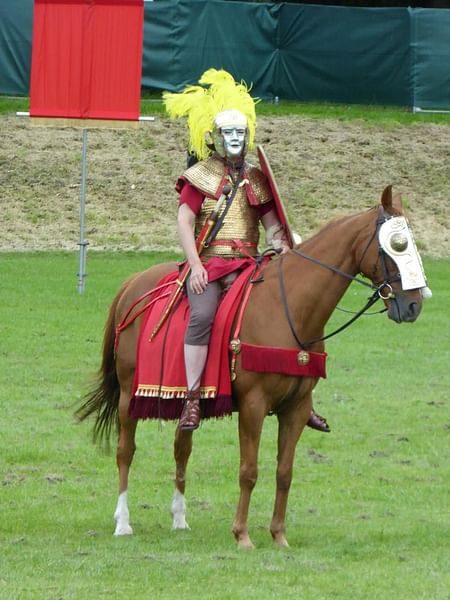

The auxiliaries saw a major change with the arrival of the Roxolani Sarmatians. They were a completely different breed of horsemen: the cataphractarii or clibanarii. Both the rider, who wore a face mask, and horse were heavily armored. Defending without a shield, the cataphract fought with a heavy 3.6-meter (12 ft) spear (contus) which was held with two hands and used for shock action. The Romans had first faced the Roxolani in Moesia in 69 CE. Tacitus commented on this meeting and the disadvantages of a fully-armored soldier and horse. During the battle, the Roxolani were hampered by the wet, slippery ground:

The superior speed of their horses was lost on the slippery roads...the day was damp and the ice thawed, what with the continual slipping of their horses, and the weight of their coats of mail, they could make no use of their pikes or their swords which being of excessive length they wield with both hands." (History 1.79)

A century earlier the Romans had seen what a Parthian cataphract could do when the Roman commander Marcus Crassus (115-53 BCE) faced them at the Battle of Carrhae, 53 BCE. Specially trained to fight on open ground, the Parthian cavalry was not like anything the Romans had ever encountered. Fighting without an infantry, Parthian warfare used lance-carrying cataphracts and lightly-armored mounted archers. These horsemen were swift-moving and rapid-firing, emphasizing agility and superb horsemanship with rapid charges and feigned retreats. Their riders used the Parthian shot where the archer would ride away at full speed, and, while spinning around in his saddle, he would shoot arrows over his horse's rump. The battle at Carrhae was among the worst military disasters in Roman history.

Completely different from the clibanarii, the Roman auxilia also used Numidian horsemen from Africa, whom they had met previously in their encounter with Hannibal (247-183 BCE) during the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE). Unlike the Roxolani, they rode without a saddle or even a bridle and were unarmored, relying on their speed and agility. They carried a light spear with a small shield and wore a short, sleeveless tunic.

Aside from these horsemen, the Romans relied on horse archers (sagittariorum), who were used "to demoralize and disorganize the enemy by inflicting losses at a distance" (Fields, 11). Southern maintains that many of the archers may have come from the East. They carried a shafted weapon, shorter than that of the infantry, and a composite bow constructed from different woods any glued together. The archers were taught to shoot from either side and the rear, using the Parthian shot.

Organization

There were two major categories of alae. Although the sources vary on the exact numbers, the ala quingenaria was comprised of 16 turmae of 30 (or 32) cavalrymen in each turma, equaling a total of 480 (or 512) while the elite ala milliaria were comprised of 24 turmae, a total of 720 or (or 768) men. Besides these two alae, there were also mixed cohorts of infantry and cavalry. The cohortes equitatae quingenaria were comprised of six centuriae (80 men in each) of foot soldiers and four turmae of horse-riders. In the cohortes equitatae milliaria, there were eight turmae and ten centuries. Many of the horsemen of the cohortes equitatae had served as infantrymen before being trained for the cavalry. In the East, many of the units contained camel riders called dromedarii. The mixed units provided a mobile patrolling and policing unit.

The alae's overall commander was a praefectus cohortes, usually of the equestrian class. Each turma was commanded by a decurion, often promoted from within the ranks, who was held responsible for their training and discipline. Like in the legions, there were other officers: the signifier alae, imaginifier, custos armorum, medicus, optio, and vexillarius.

Training

Cavalry training for the new recruits (tironis) was long, about four months, and demanding, especially for those without riding experience – it is not known whether or not these four months included training on horsemanship. Like all other recruits, the recruit or tiro was first administered an examination (probatio) to assess his fitness. Besides learning how to ride, he was taught how to build palisades and dig ditches, essential skills when building campsites. After learning the necessary skills of riding on horseback, the recruit was taught to fight dismounted like the infantry, if it became necessary in battle.

To perfect their skills, the prospective cavalrymen engaged in tournaments, practicing tactical maneuvers, pursuits, retreats, and countercharges while also gaining experience with the javelin and thrusting spear. After completing the training, the recruit would be assigned to a turmae and administered the oath to the Roman emperor. Like the infantry, he would be forbidden to marry and was subject to the same harsh discipline. The pay was good with rewards that included cash as well as access to loot and booty, although the cash was given to the unit, not an individual, for performing well.

Battle Formation

The auxiliary cavalry proved their mettle in both peacetime and Roman warfare. Before the battle, with the army on the march, the cavalry acted as scouts, protecting both the rear and flanks. Fields wrote that the cavalry "undertook all those roles that required mobility and speed" (47). After establishing the camp, the cavalry and auxiliary infantry would man the outposts. In battle, the type of terrain dictated the alignment of the auxiliaries. In the typical formation – the triplex acies or three lines – the auxiliary cohorts were stationed on either side of the center formed by the legions while the alae protected the flanks. Tacitus wrote of the battle formation used by the Roman commander Vocula against Gaius Civilis, leader of the Batavian Revolt of 69-70 CE:

All he could do in the confusion was to order the veteran troops to strengthen the center. The auxiliaries were dispersed in every part of the field. The cavalry charged but, received by the orderly array of the enemy, fled to their own lines. What ensued was a massacre rather than a battle. (History 4.33)

Although the auxiliaries were not supposed to charge the enemy infantry, they were expected to pursue the retreating enemy and keep them from rallying. The cavalry "was highly confident, and because it was well-trained and led, was able to rally more easily after a pursuit and fight and keep its formation" (Fields, 51).

Equipment

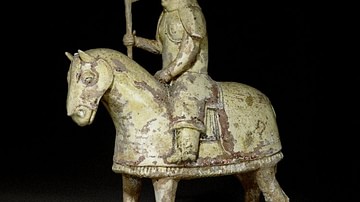

The cavalry's helmets were made of iron or copper and covered the ears and nape of the rider's neck, protecting the side and back of the head, unlike the infantry's helmet which covered the ears. The cavalry needed the extra protection of the face to prevent blows to the side or back of the head while the infantry needed to be able to hear the centurion barking orders. The crown of the helmet was reinforced with cross braces secured with rivets. Like the infantry, the cavalry wore boots (caligae), often with spurs. Body armor consisted of two types: the lorica hamata (mail armor) and the lorica squamata (scale armor). Only the infantry wore the lorica segmentata (segmented armor). Their shields were flat, either oval or hexagonal. They carried a light spear used for throwing or thrusting. In addition, they used the spatha, a double-edged broadsword (66-90 cm or 26-36 inches in length) as well as the 3.6-meter (12 ft) contus.

The most important piece of equipment was, of course, the horse. Southern wrote that the supply of good horses was a constant headache for the cavalry units. They were obtained through capture, a levy on a defeated enemy, and breeding. The care of the horse was the responsibility of the individual cavalryman. And, of course, there was a veterinarian in each unit. Although the Romans did not use stirrups, proper protection was also necessary for the horse: the chamfron protected the face (with ear and eye guards), the peytral hung from the horse's harness, and the armored barding protected the body of the horse. The Romans used a four-horned saddle with a saddlecloth beneath it to protect the horse from chafing. With proper training for both rider and horse and the essential equipment, the auxilia was prepared for either peace or war.