The Pinson Mounds are a State Archeological Park in Madison County, Tennessee, USA enclosing a prehistoric Native American religious site comprising earthen mounds built during the Middle Woodland Period (c. 200 BCE - 500 CE). Although there may originally have been more, the site presently includes 15 large earthen mounds ranging up to 72 feet (22 m) in height.

The largest of the mounds is Sauls Mound (also known as Mound 9) in the center of the complex which seems to have been the focal point of religious rituals. The mound was named for John Sauls, the owner of the property the mounds were found on. The other mounds are arranged in apparent symmetry to perhaps focus natural, spiritual, energies. The site itself is named for its discoverer Joel Pinson, a 19th-century land speculator who was sent to survey the area after the Chickasaw Nation ceded the land to the state of Tennessee in 1818. The original name of the site, if it had one, is unknown.

Excavations of the site were first initiated in the late 19th century but did not go far. Professional archaeological excavations were not begun until the 1960s with more serious efforts initiated in the 1980s. These efforts have unearthed artifacts strongly suggesting the site was used exclusively for religious purposes and was never a residential site except for the so-called Cochran Area, located away from the central mounds, which seems to have served as a temporary residence for people participating in rituals. The site was declared a State Park in 1974 and is registered as a National Historic Landmark and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in the USA.

The Woodland Period

The Woodland Period is a modern-day designation for the era c. 500 BCE - 1100 CE, a transitional time between the Archaic Period (c. 8000-1000 BCE) and the Mississippian Culture (c. 1100-1540 CE). The Archaic Period produced the first monumental earthen mounds in North America which are thought to be a response to the development of religious beliefs formed earlier while the Mississippian Culture is considered the most mature expression of those beliefs and Native American culture generally as evidenced by large urban centers such as Cahokia and Moundville.

While there is some logic behind this chronology, it is largely artificial – a convenient means by which scholars study prehistoric North America – as elements of the so-called Archaic Period are evident in the Woodland Period and, likewise, Woodland Period practices, tools, and technology are evident among the people of the Mississippian Culture. It should also be noted that not every scholar, archaeologist, or historian agrees on the approximate dating of any of these cultures and dates should, therefore, be regarded more as probabilities than certainties.

With this in mind, the Woodland Period is divided into three subperiods:

- Early Woodland – c. 1000-200 BCE

- Middle Woodland – c. 200 BCE - 500 CE

- Late Woodland – c. 500 - 1000 CE

Religious beliefs, evidenced by grave goods buried with the deceased, began to develop much earlier but are fully apparent during the Archaic Period in more elaborate graves. These beliefs seem to have been developed further during the Woodland Period with the construction of larger mounds in greater numbers some of whose artifacts strongly suggest a religious purpose. A high degree of technical skill in mound-building is already evident in the Archaic Period in sites such as Poverty Point (in modern-day Louisiana) and it is possible that the work of the people of that region influenced those of other areas (though this is not necessarily so). It seems as though mound-building, though following a similar basic pattern of construction, was developed by individual groups distinct from one another as a reflection of their spiritual beliefs.

Religious Development

Religious beliefs are thought to have first developed during the period known as the Dalton-Folsom Culture (c. 8500-7900 BCE) when grave goods begin appearing, but it is equally possible that some kind of religious practice was observed earlier which simply did not include providing the deceased with grave goods and, also, cremation seems to have been a common practice prior to this time, during it, and also later. By the time of the Woodland Period, however, burials had become more or less standardized among the various tribes/nations. Those of the lower class were buried with simple goods – which still represents a significant sacrifice to the living as ceramics and tools took time and resources to make – while the upper-class and nobility were interred with more elaborate goods. Scholar Jake Page comments:

Phenomenal amounts of grave goods accompanied the dead in the tomb – thousands of freshwater pearls, for example, and copper ornaments of all sorts, as well as objects made of mica, silver, and tortoiseshell – mostly exotic objects made of exotic materials. Figurines and carved pipes were relatively common and showed a similarity in design throughout the regions where such burials became the fashion – notably the Ohio Valley, Illinois, and throughout the Southeast. (67)

The elite was often buried in the mounds, though not always as so-called charnel-house tombs of wood were also used. The mounds were used by the later Mississippian Culture as tombs, residences of the elite (the homes built on their flat tops), other uses not yet understood, and definitely for religious rituals. These rituals were performed regularly in communities to appease the gods/spirits, to seek guidance, give thanks, and make supplication for the prosperity of the people. One such ritual, known to have been continued into the Colonial Period, was conducted to give back to the earth by reawakening its energies which was thought to encourage larger harvests. Scholar Larry J. Zimmerman explains:

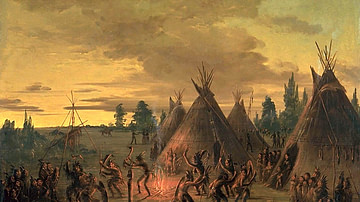

At the core of long-established Native American beliefs is one that the rhythms of the universe are like those of a steady drumbeat. In order to be renewed, the rhythms and cycles of nature require human participation in the form of rituals that mark important points in the cosmic cycle. Such Earth-renewal rituals are usually based upon the seasons, or crucial times in the food-supply calendar. These first-food ceremonies are profoundly important – celebrating fertility and marking the renewal of a subsistence cycle, which incorporates everything from the appearance of the first salmon or buffalo to the growth of corn. (230)

It is possible, and quite likely, that these were the kinds of rituals performed at Pinson Mounds. There is no evidence of permanent, year-round, residency – only of temporary housing near the mounds which was used at intervals – while the artifacts found at the site suggest regular ritual use over a significant length of time.

The Pinson Mounds

The Pinson Mounds were constructed in stages over many years by people harvesting soil using stone tools to dig with and baskets or animal hides to carry the earth to the mound site. The site’s mounds represent the work of a large labor force organized and directed by some central authority. Who these people were is unknown and it is also impossible to know whether they were all of one community or if the site was originally conceived of and built by members of different communities working together toward a common goal. The original builders may have been the ancestors of the Chickasaw Nation as they eventually held the lands in the 19th century.

The site was purposefully designed and built in three sections:

- Eastern Section

- Inner Complex

- Western Section

At other sites, such as Moundville, mounds were constructed facing a central mound used for religious rituals with others used for residential or burial purposes but at Pinson Mounds there seems to have been mounds used exclusively for a religious purpose while other mounds were used for burials and other purposes not yet defined by archaeologists. The three sections seem to have been built during the same time period, roughly 1-200 CE, with construction ongoing on all three in stages.

The Eastern Section includes rectangular mounds with flat tops but also Mound 30 which is shaped like a bird. It is unclear whether it was originally designed this way or if the wear of the years and later cultivation by Chickasaw natives and colonial English shaped it. The most significant structure in this section is the Eastern Citadel which has been determined to have been used entirely for ritualistic purposes. Mound 28 is aligned with the sunrise of the summer solstice as well as Sauls Mound of the Inner Complex.

Sauls Mound (also known as Mound 9) is situated in the center of the Inner Complex and is also believed to have been used exclusively for religious rituals. The rectangular mound has its four corners aligned with the cardinal directions with its eastern corner also aligned with Mound 28 of the Eastern Section. At 72 feet in height (22 m) it is the largest mound in North America after Monks Mound at Cahokia. Other mounds in the Inner Complex also provide evidence of ritualistic activity but one, Mound 12, was used for the burial of members of the upper class.

The Western Section includes the Ozier Mound (also known as Mound 5), the Twin Mounds (Mound 6), and – located approximately 700 feet (200 m) away – the so-called Cochran Area, which provided temporary housing for guests. It does not seem the Cochran Area was used for long-term habitation by the laborers at the site. The Twin Mounds were used for burial while the Ozier Mound, the second-largest at the site after Sauls Mound, served a ritualistic purpose. Archaeologists Robert C. Mainfort, Jr. and Richard Walling, who took part in the 1989 dig, note:

Although relatively few definable features have been identified to date, we feel confident in suggesting that [Ozier Mound] represents a specialized activity surface associated with ritual behavior. Significantly, the uppermost preserved summit of Ozier Mound lacks evidence of posts and/or possible structures, accumulated midden [garbage] deposits, and large quantities of faunal and floral remains that characterize the summits of some other Middle Woodland platform mounds. (117)

Mainfort and Walling also note the presence of a sand covering in between the layers of some mounds which they suggest, at least in some cases, served to top the summit as a given mound was under construction. Although they offer no explanation for the use of sand beyond said covering, it is possible it was used in the same way as established later at Monks Mound of Cahokia.

Archaeologist William Woods of the University of Kansas, who worked at the Cahokia site for over 20 years, established that sand was used to prevent capillary action and thereby preserved the integrity of Monks Mound. Scholar Charles C. Mann cites Woods’ observations after noting that Monks Mound at Cahokia is built on an enormous slab of clay (as some Pinson Mounds are as well):

The sand acts as a shield for the slab. Water rises through the clay to meet it but cannot proceed further because the sand is too loose for further capillary action. Nor can the water evaporate; the clay layers atop the sand press down and prevent air from coming in. In addition, the sand lets rainfall drain away from the mound, preventing it from swelling too much. (298)

It is unclear whether this same engineering technique was used at Pinson Mounds, however, as some mounds – such as Sauls Mound – show no evidence of sand whatsoever, and Mounds 15 and 28 follow this same paradigm. If the builders of Pinson Mounds did use the same sort of technology as those at Cahokia, they did so unevenly. Ozier Mound, thought to be the first constructed in the latter half of the 1st century BCE, does give evidence of sand use, as noted, and it seems that later builders chose not to follow this model uniformly for unknown reasons.

Discovery & Excavation

The area of West Tennessee surrounding Pinson Mounds was purchased from the Native American Chickasaw Nation as part of the Treaty of 1818. A land speculator named Joel Pinson was sent to survey the area in 1820, became the first white person of European descent to see the site, and so had it named for him. The site generated little interest until a journalist named J.G. Cisco began writing a series of articles on the mounds in the late 1800s. Cisco’s articles attracted the attention of one William Myer of the Smithsonian Institution in 1916 who traveled to the site and mapped it. Mainfort and Walling write:

The earliest map of the site appeared in an obscure article by William Myer (1922), an intermittent employee of the Smithsonian Institution who recorded nearly three dozen mounds and…earthen embankments. Although many of the mounds and most of the embankments reported by Myer are now known to be natural landforms, researchers have retained Myer’s mound numbering scheme. Prior to the 1980s, Pinson Mounds had only been cursorily investigated by professional archaeologists and, although this initial research suggested that major use of the site occurred during the Middle Woodland Period, it was generally assumed at least some, if not all, of the large platform mounds were of Mississippian affiliation. (113)

The similarity of the Pinson Mounds and those of the Mississippian Cahokia and Moundville, of course, suggested this conclusion, but excavations in the 1980s proved conclusively that the site was created much earlier and is definitely the creation of Middle Woodland Period communities. Even so, the site has only been partially excavated as it is protected by State ownership as a park since 1974, and full excavation has been discouraged in the interests of preserving the mounds intact.

The Pinson Mounds State Archaeological Park today preserves 15 of the 30 mounds originally mapped by Myer surrounded by over 1,200 acres of land, camping facilities, and hiking trails. The Pinson Mounds museum on-site features an 80-seat theater, 4.500 feet (1370 m) of exhibits, a “Discovery Room” encouraging interaction with the past, and also houses the offices of the West Tennessee Regional Archaeological Office. Pinson Mounds is one of the most popular tourist attractions of the area, drawing thousands of visitors to the site annually for the opportunity to explore the woodlands, view the mounds, and learn the history of the First Nations to occupy North America.