Rose-and-nightingale paintings and patterns (gul-u-bulbul) are a subtheme of the bird-flower (gul-u-morḡ) genre in Persian art. Bird-and-flower paintings are of Chinese origin and include pictorial elements such as flowers and plants, birds, and occasionally butterflies. This motif was then appropriated by the Persians and throughout the centuries evolved from being a decorative element within the art of books to an independent genre of painting.

Both the rose and the nightingale have important status within Persian art and literature, with roses also having a conspicuous role in Persian traditions, ceremonies, and economics. From the pre-Islamic era and Zoroastrian rituals to the Islamic period, roses have enjoyed a significant position both symbolically and practically. Roses have been associated with the prophets of Islam, especially Prophet Muhammad (570-632 CE), and they were one of the main Persian exports during the Safavid era (c. 1501-1739), which also contributed to their more abundant presence in art. The importance and presence of this motif increased so much during the Qajar Dynasty (1794-1925) that it even came to symbolize the country itself. The word 'rose' (gul) also became a generic term for all flowers. As Layla S. Diba notes:

The bird and flower decorative theme was one of the most prominent in Persian art, originating in manuscript illustration and evolving as a decorative motif and independent painting genre. This theme enjoyed such popularity due to its universal appeal and range of both earthly and divine floral meanings which it conveys. (12)

Origin

The bird-and-flower subject was popular in China from the early Tang Dynasty (618-907) and was one of the major types of Chinese painting which included birds, flowers, insects, and pets. Chinese artist-scholars depicted this motif using different stylistic and technical approaches ranging from realistic to overtly expressionistic. Regardless of the method of painting, the bird-and-flower motif had a symbolic meaning and reflected the ideas of the artist-scholar. Although the bird-and-flower theme (especially roses) had been used in Persian literature and poetry since the 11th century and throughout its golden age, it only appeared within the art of books during the Ilkhanid period in the 14th century due to Chinese influence.

Development & Symbolism

The rose symbolized perfection, beauty, and elegance, and the bird (nightingale) represented the human spirit in Persian mysticism. Together the pair stood as a metaphor for the loved and the beloved. This love could be both earthly and divine, symbolizing the soul's yearning for union with God. From the 16th century onward the rose and nightingale motif began to break free from the frames of manuscript illustrations and sporadically appeared in decorative arts and courtly portraits.

It was during the 17th century that the bird-and-flower motif underwent a noticeable change. It began to visually distance itself from its Chinese prototypes and illustrate European influence following Iran's increased cultural exchange with the West. Moreover, the motif was used to decorate the surfaces of lacquer objects and textiles, and as a decorative pattern in architecture. During the Zand Dynasty (c. 1750-1779) the bird-and-flower motif gained even more momentum due to the demand of European travelers and began to appear on all media while reaching its peak during the Qajar Dynasty. Thus it can be concluded that the development and evolvement of the bird-and-flower motif can be divided into two timeframes: the Islamic period until the mid-Safavid Dynasty, which illustrates a Chinese influence, and the post-Safavid and Qajar period, which showed more of a European influence.

Contrary to the rather dynamic compositions of the bird-and-flower paintings of the Safavid Dynasty, the almost symmetrical compositions of the Zand Dynasty were more tranquil with less movement and more frequent use of roses of a hundred petals (gol-e sadbarg). A rather similar visual pattern but once again with the movement of the works of the Safavid period can be traced in the paintings of the Qajar Dynasty.

In each period, the position of the birds and the flowers within the composition and the overall mood of the painting reflected the poetic imagination of the artists themselves. The birds were depicted as being awake, asleep, or busy hunting, each of which contained a different spiritual and literary meaning and connotation. During the Qajar Dynasty, there was also an emphasis on the decorative aspect of this motif as is evident from the highly decorated lacquer pen and vanity boxes and mirror cases of this period.

Artists

The best-known artists who experimented with the bird-and-flower motif on various media were Ali Ashraf, Fathallah Shirazi, and Luft'Ali Suratgar Shirazi from the Qajar Dynasty. Active in the mid-18th century, Ali Ashraf was a leading lacquer artist who was well known for his bird-and-flower designs. His style and tradition were somewhat continued by Luft'Ali Suratgar Shirazi (active c. 1802-1871). A master portraitist (hence being known as 'Suratgar', a Persian term for a painter of portraits), Luft'Ali Suratgar was also one of the most prolific and well-known bird-and-flower artists who mainly worked in lacquer and watercolor. In his works, he paid close attention to the natural color and form of the flowers and depicted the birds in various positions.

In Persian mysticism and literature, the bird could be viewed as a symbol of the human spirit and, as such, a representation of the painter's spiritual and mental condition. Thus the different positions of the bird in Luft'Ali Suratgar's paintings could also contain a deeper mystical meaning underneath their charming visual aesthetics. In his works the birds are at times depicted with open or closed eyes; the former possibly denoting a person conscious of the cosmos and the physical world around him and the latter alluding to a person who has closed his eyes to the physical world and desires and perceives with the spiritual eye of the mind. Another common position in Luft'Ali Suratgar's paintings is a bird hunting for insects such as butterflies, which could be a representation of the constant conflict and struggles between life and light and annihilation and darkness in which the former always conquers.

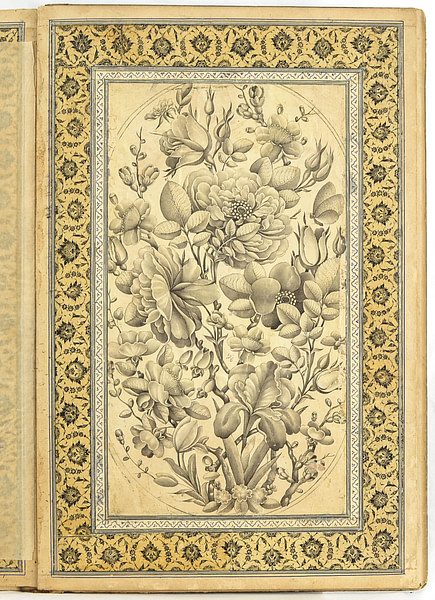

Fathallah Shirazi is also known for his bird-and-flower paintings and drawings. He was a court painter to Nasir al-Din Shah (r. 1848-1896), and although he was known mainly for his lacquer paintings, Fathallah Shirazi also used flowers as his subject while experimenting with ink on paper which resulted in a beautiful album of monochrome flower paintings.

The above names are only a few of the many artists who have used the bird-and-flower motif both as an independent subject and a complementary element to the painting in various media, contributing to its development as a genre. Many of the artists were active in the province of Shiraz, which held a central position in the appearance and development of the bird-and-flower motif. The School of Shiraz (also known as the School of Zand) appeared during the Zand Dynasty.

Conclusion

The bird-and-flower motif held an important position both in the Persian art of painting and literature. Jack Goody notes that flowers pervaded Persian literature like nowhere else except for China. While the presence of this motif within Persian poetry predates its appearance in the paintings, the bird-and-flower subject (along with its subthemes such as rose and nightingale) would evolve to become an independent genre adorning the pages of the albums, and the surfaces of decorative objects and both urban and religious buildings.

Although the bird-flower motif was used both as a mere decorative pattern and a symbolic subject, depicted with a stylized or realistic approach, the beauty of its elements and the harmony of its compositions attracts the attention of all to this day. Adapting the motif from China and also implementing the European taste along the way, the Persians turned the bird-and-flower motif into an integral part of Persian art and culture.