Muqarnas is a three-dimensional architectural decorative element that flourished in its most complete form mainly during the Islamic period and is most pervasively used in domes and semi-domes. One of the key features of this mesmerizing element is its geometry which still remains a mystery and is a subject that required a deeper study by artists and art historians.

Etymology & Origin

There are still debates regarding the etymology of the word 'muqarnas'. Mohammad al-Asad suggests some possibilities among which is the Greek word koronis, which has also informed the English word cornice.

The origin of this decorative element is also a subject of debate. Some early and simpler examples of muqarnas have been traced back to Iran during the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE), becoming more complex throughout the time of Parthia (247 BCE to 224 CE) and the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE); thus, suggesting an Iranian origin for this architectural element. Other scholars have suggested that muqarnas in its current form developed and flourished during the Islamic era, and examples of it can be found as early as the 9th and 10th centuries in locations such as north Africa, northeast Iran, and Egypt. They mostly agree that Baghdad, at the center of the Islamic world, is where the current form first appeared and not too long after spread throughout the Middle East and in some cases to the West. What is known for sure is that, by the 12th century, due to its pervasive use in both religious and secular buildings, muqarnas had become one of the most characteristic staple features of Islamic architecture.

According to Titus Burckhardt, muqarnas consists of small carved or molded units assembled on top of one another according to a number of models based on various factors such as the profile of the arches and the level of concavity of the vaults. He briefly describes it as:

A case of having cupola supports in the form of niches, repeated one after the other in the same way as the cells of a honeycomb are repeated or as crystals cluster together according to the radiation of their axes. (Burckhardt, 73)

Because of its application in various Islamic territories, distinct types of muqarnas executed with different materials can be found depending on the geographical location and the period in which they were created and used. For example, according to Vincenza Garofalo, while bricks covered with plaster and colorful tiles were used in Iran and Iraq, wood covered with plaster was seen in Africa, and stones were common in Syria, Egypt, and Turkey.

Function & Aesthetics

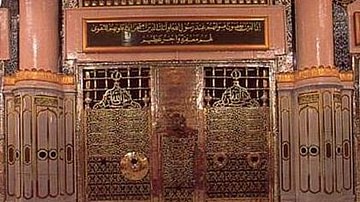

Muqarnas are mostly used in domes and semi-domes, but this architectural decorative element can also be seen in mihrabs (niches in the walls of the mosque that indicate the direction of the prayer) and iwans (a rectangular space, walled on three sides and open on one). It has been suggested that muqarnas are associated with Islamic theology and aesthetics while they also serve a decorative function. As a decorative element, muqarnas facilitates a smooth and seamless transition from a flat and vertical plane to a horizontal and curved one. Furthermore, once illuminated by natural light, the small units of its geometrical shapes and forms create a fantastical effect that is further enhanced when the units are covered with colorful tiles or in more complex examples, with mirrors.

Burckhardt suggests that muqarnas have both a static and rhythmical character that corresponds to that of the base and the dome (the square and the circle) and what they symbolically stand to represent, i.e. the earth and heaven. From a theological standpoint, muqarnas can also be seen as expressing the relationship between the universe and its creator.

A view which combines both decorative and structural functions suggests that the origins of muqarnas may be found in Islamic theology which promotes an occasionalist view of the universe whereby the continued existence of anything is dependent on the will of God. Muqarnas is then a way of expressing this view of the universe where the dome appears to stand without visible support. (Peterson, 208)

The same theory is suggested by Yasser Tabbaa who focuses on the shape of muqarnas and its division into small units:

The division of the dome into segments implied a certain conception of not just the dome, but of its referent, the universe. (Tabbaa, 68)

According to him, the universe which the dome stands to represent is constantly created and ever-changing and thus needs an eternal creator that keeps it from collapsing. In this light, Tabbaa studies the different qualities and characteristics of muqarnas individually. The effects of the lights, both natural and superficial, on the painted surfaces of the small units of muqarnas communicate the idea that colors, shapes, and luminosity are accidents in this world and subject to continuous change according to the will of God. Furthermore, by drawing attention away from the squinches and smooth domes, the idea was communicated that the small but distinct units of muqarnas were kept whole by the will of God, not a man-made squinch.

Some Examples

Muqarnas appeared in different forms, shapes, and materials depending on the region and period in which they were created. The Alhambra palace (Qal' at al-Hamra) in Granada, Spain was built in the mid-13th century during the Nasrid dynasty (1230-1492), the last Muslim dynasty in the Iberian Peninsula. The palace has since undergone many renovations, but it contains some of the most fascinating examples of muqarnas worked in different parts and sections of its architecture, two of which are located in the halls of the Palace of Lions (Palacio de los Leones). The ceiling and dome of the Hall of the Abencerrajes (Sala de los Abencerrajes) and the Hall of Kings (Sala de los Reyes) are adorned with muqarnas in a rather complex form which once viewed from the bottom, leaves the viewer in awe.

Built to the order of Shah Abbas I (also known as Abbas the Great, 1571-1629) of the Safavid dynasty, Shah Mosque was part of the architectural initiative taking place in Isfahan following Shah Abbas' decision of relocating the capital of the Persian empire from Qazvin to this central city. This masterpiece of Persian architecture is located in the Naghsh-e Jahan Square and its semi-domed grand entrance iwan, which measures 27 meters in height and boasts one of the most fascinating examples of muqarnas that appears to support the minaret's rooftop balcony. Covered with polychrome mosaic tiles mainly in turquoise, cobalt, and navy blue, the muqarnas decorations of the Shah Mosque amaze the visitors upon their entry to the building. In fact, this iwan presents one of the greatest examples of color play on a grand scale.

Also part of this architectural project was the Chehel Sotoun Palace (literally translating to Forty Columns Palace). The initial pavilion mansion of this building was constructed under the rule of Shah Abbas the Great, while the rest of the halls were added to the structure under the reign of Shah Abbas II (1632-1666). Although the palace is adorned by numerous large frescoes and painted tile panels, one of its most fascinating sections is the building's large porch which faces the east side. The porch itself consists of two sections including the Hall of Mirrors which serves as an entrance to the building. As the name suggests, the space of this hall is adorned with fine mirror work and contains one of the most beautiful examples of muqarnas semi-domes, which is also decorated with small pieces of mirrors, adding to the delicacy of this architectural element.

Another fine example of muqarnas can be seen on the body of the Qutb Minar located in the Qutb complex in Delhi, India, which was constructed to the order of Qutb al-din Aibak (1150-1210). This brick minar (minaret) is one of the tallest of its kind and is a fine example of Indo-Islamic architecture. Due to its height, this minaret could not be used for calling to prayer, thus it became conceived as a victory tower. Being inspired by the minaret of Jam in Afghanistan, the Qutb Minar is designed in different stories, each of which is separated from the other by a projecting balcony. These balconies are supported by stalactite muqarnas that add a unique feature to the overall design of the tower.

Whether used in its simplest form or the most complex geometry, muqarnas continues to be an inseparable element of Islamic architecture expressing both an aesthetic and theological function.