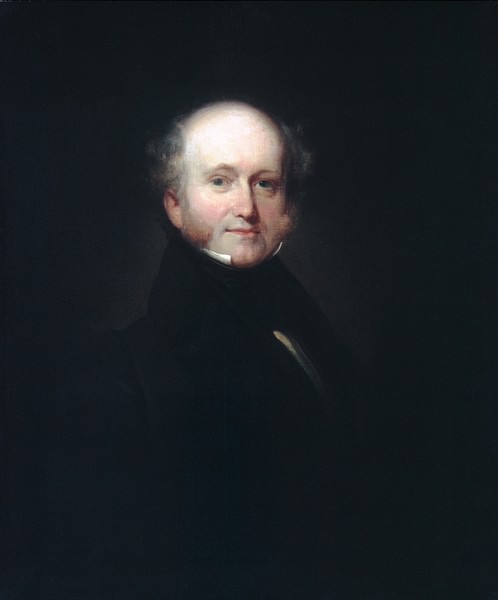

Martin Van Buren (1782-1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States. An ambitious and cunning man whose political tricks earned him the nickname 'the Little Magician', Van Buren was a talented organizer, establishing such political machines as the Albany Regency in New York and the Democratic Party on a national level. The handpicked successor of Andrew Jackson (1767-1845), Van Buren fared less well in his presidency than his illustrious predecessor; his single term was marred by the Panic of 1837, which contributed to his loss in 1840. After two more failed presidential bids, Van Buren died in 1862 at the age of 79.

Early Life

Martin Van Buren was born on 5 December 1782 in the small rural town of Kinderhook, New York. He was the third of five children born to Abraham Van Buren, a farmer and tavernkeeper, and his wife Maria Hoes Van Halen. Both of his parents were of Dutch descent, and, indeed, Van Buren primarily spoke Dutch for most of his childhood and did not learn English until he began attending school; he remains the only US president whose first language was not English. He received a rudimentary education at the village schoolhouse before studying at Kinderhook Academy. In the evenings, he would help his father run the family tavern, and by interacting with the guests travelling between New York City and the state capital of Albany, Van Buren developed the social skills that would serve him well as a politician.

In 1796, Van Buren began reading law under the prominent Federalist attorney Peter Silvester and his son Francis. While clerking for the Silvesters, Van Buren began taking on civil cases in the local justice's court, where admission to the bar was not required, and became regarded as the champion of the common man. His popularity around his hometown of Kinderhook quickly grew; after one victory, he was carried out of the courthouse on his clients' shoulders to the cheers of the gathered crowd (Brooke, 288). He completed his legal studies in New York City and passed the bar in 1803, returning to Kinderhook to set up his practice. On 21 February 1807, Van Buren married his childhood sweetheart, Hannah Hoes, in Catskill, New York. The marriage would produce six children, four of whom would live to adulthood. Sadly, Hannah died of tuberculosis in February 1819; the distraught Van Buren never remarried.

New York Politics & Albany Regency

As his father had hosted gatherings for the Democratic-Republican Party at his tavern, Van Buren had grown to admire the ideals of that party's founder, Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), including limited government and greater personal liberties. In 1812, Van Buren ran for election to the New York State Senate on a platform opposing the national bank and supporting the War of 1812 (1812-1815) against Britain. After winning the election, he served two terms in the State Senate and later served as New York Attorney General from 1815-19. Van Buren consistently opposed the policies of DeWitt Clinton (1769-1828), who was elected governor in 1817, and he became the leader of an anti-Clintonian faction called the 'Bucktails' because of the emblems they wore in their hats at party meetings.

The centerpiece of Clinton's agenda was the proposed construction of the Erie Canal, an ambitious internal improvement project that would connect Lake Erie to the Atlantic Ocean. Initially, Van Buren and the Bucktails opposed the canal, fearing that it would only solidify Clinton's hold over New York politics. However, once it became clear that the canal was popular with voters, Van Buren changed his tune. Not only did he act like he had always supported the canal but he also played a major role in pushing the canal bill through the state legislature. This kind of political sleight-of-hand, in which he made sure to always emerge on the winning side, earned Van Buren the nickname 'the Little Magician'. Having failed to defeat Clinton on policy, Van Buren decided to mobilize the opposition against him. He transformed the Bucktails into a well-oiled political machine that relied on systems of patronage and partisan newspapers to get their anti-Clinton message out. The Bucktails travelled to every corner of New York, thereby extending their "network of alliances from Albany to the remotest areas of the State" (Remini, 344). In this way, the Bucktails soon took control of Albany, establishing an informal political network known as the Albany Regency.

In February 1821, the New York legislature – controlled, of course, by the Albany Regency – sent Van Buren to the US Senate. A short, well-dressed man with reddish hair and a prominent nose, Van Buren made an impression on his new colleagues who soon referred to him as the 'Red Fox of Kinderhook'. Though not a gifted orator, Van Buren made sure to increase his profile by giving frequent speeches on the Senate floor, after thoroughly researching the topics. In the crowded, five-way presidential race of 1824, Van Buren supported his friend William H. Crawford, lobbying for congressmen to vote for him when the tight race was handed off to the US House of Representatives. Ultimately, the election was won by John Quincy Adams (1767-1848), who quickly alienated Jeffersonians like Van Buren with his high tariff policies and support for the national bank.

Father of the Democratic Party

By now, Van Buren was a strong believer in a two-party political system. The Founding Fathers had deplored partisanship and had joined political parties only out of necessity. Van Buren, on the other hand, felt that two parties, each with distinct political philosophies, would be the most efficient way to organize, elect officials, and achieve political goals. In 1827, as the next presidential election neared, Van Buren sought to build such a party around Andrew Jackson, a war hero and Tennessee frontiersman. Using Jackson as a rallying point, Van Buren built a loose coalition of politicians, like Crawford, Thomas Hart Benton (1782-1858), and John C. Calhoun (1782-1850), who shared his vision for a return to Jeffersonian ideals, like agrarianism, personal liberties, and states' rights. This coalition would become known as 'the Democracy' and would eventually be called the Democratic Party.

In 1828, DeWitt Clinton unexpectedly died of a heart attack, leading Van Buren to resign from the Senate to run for New York governor. Backed by the Albany Regency, he ran on a ticket that he called 'Jacksonian Democrat' and won the election by 30,000 votes. Jackson, too, won the presidential election, thanks in no small part to the efficient political machine Van Buren had built. In February 1829, President-elect Jackson tapped Van Buren as his secretary of state; the 'Little Magician' accepted, resigning the governorship after a tenure of only 43 days. As secretary of state, Van Buren performed ably, striking trade deals with both Britain and the Ottoman Empire that opened the British West Indies and the Black Sea to American merchants. However, Van Buren used the position to get closer to Jackson himself, often going on daily horse rides with the president. Before long, Van Buren emerged as one of Jackson's closest and most trusted advisors.

In Jackson's Administration

Part of the reason why Van Buren became so trusted in Jackson's eyes was his handling of a scandal called the Petticoat Affair. Early in Jackson's presidency, the wives of his cabinet members refused to associate with Peggy Eaton, wife of the secretary of war, due to her scandalous reputation as an adulteress. Jackson, an authoritative man who could suffer no discord in his administration, sided with the Eatons and urged his cabinet secretaries to control their wives; when this did not happen, the president grew frustrated, feeling as though he were losing control of his own cabinet. Sensing a chance to further ingratiate himself with the president, Van Buren arranged for the entire cabinet to resign, offering it as the best way to solve the problem while saving Jackson from further embarrassment. Van Buren took the lead and was the first to resign, confident that he would be rewarded for his efforts. His plan worked – after the troublesome cabinet members were pressured into resignation, Jackson was free to appoint new, more loyal secretaries. "Well indeed," wrote one newspaper, "may Mr. Van Buren be called 'The Great Magician' for he raises his wand, and the whole Cabinet disappears" (quoted in Howe, 339).

But Van Buren was not yet finished. Having built the political machine that helped carry Jackson to the White House, he viewed himself as his natural successor, but if he hoped to succeed Jackson to the presidency, he would have to get rid of Vice President John C. Calhoun. Since Calhoun's wife had been the first prominent lady to snub Peggy Eaton, Van Buren had no difficulty convincing Jackson that the Calhouns were disloyal. As the icing on the cake, he produced letters that Calhoun had written in 1818, in which he had condemned Jackson for his dubious military actions in Spanish Florida. For Jackson, this was enough to convince him that Calhoun was 'a villain'; from then on, the vice president was isolated from the administration. In August 1831, Jackson attempted to reward Van Buren by nominating him as ambassador to Britain. Calhoun, intending to get revenge on the 'Little Magician', cast the tie-breaking vote against the nomination; convinced that this would end Van Buren's career, Calhoun told a friend that the vote would "kill him dead, sir, kill him dead" (quoted in Howe, 338). But Calhoun was wrong. In his 1832 re-election bid, Jackson kicked Calhoun off the ticket and replaced him with Van Buren as his running mate.

On 4 March 1833, Van Buren was inaugurated as Jackson's new vice president. In this capacity, he continued to act as one of Jackson's closest advisors. He supported the president's efforts to kill the Second Bank of the United States (BUS) in the Bank War, supported the administration's controversial Indian Removal policies, and urged conciliation with South Carolina during the Nullification Crisis. Jackson valued Van Buren's loyalty and eventually considered him his heir. As the election of 1836 approached, Jackson supported Van Buren's candidacy in the belief that the 'Fox of Kinderhook' would continue his agenda. With Richard Mentor Johnson of Kentucky as his running mate, Van Buren ran against several candidates from the new Whig Party, which had been formed in opposition to Jackson and his policies. Van Buren won 50.9% of the popular vote and 170 electoral votes, enough to put him over the top.

Presidency

On 4 March 1837, Van Buren was sworn in as the eighth US president. In his inaugural address, he promised to preserve the legacy of the Founders, as well as that of his "illustrious predecessor". Indeed, the shadow of Jackson loomed large over the inauguration, with many expecting that Van Buren's presidency would be little more than Jackson's third term. "For once," remarked Thomas Hart Benton, "the rising sun was eclipsed by the setting sun" (quoted in Howe, 484). Van Buren was quick to signal his intention to continue the Jacksonian agenda. He retained most of his predecessor's cabinet secretaries and lower-level government appointees; the one man he did appoint, Joel Roberts Poinsett as secretary of war, was a staunch Jacksonian Democrat. Van Buren highly valued his cabinet, periodically consulting them for advice throughout his term.

While the legacy of Jackson's presidency certainly benefited Van Buren in the form of political support, it also came back to haunt him. On 10 May 1837, only two months into Van Buren's presidency, several New York banks refused to convert paper money into gold or silver, on the grounds that their currency reserves were running low. Banks across the nation followed suit, triggering a financial crisis known as the Panic of 1837, which was followed by a five-year economic depression. Van Buren blamed the crisis on the banks, accusing them of having overextended their credit. The Whigs, however, blamed Van Buren and his ilk of Democrats. Had they not dismantled the BUS, there would have been a national bank to ensure that the smaller state banks did not irresponsibly print paper money. Whigs also blamed the crisis on the 1836 Specie Circular, which had been implemented by Jackson and stipulated that all government lands must be purchased with gold or silver. Cries of 'Repeal the Circular' went up across the nation, but Jackson urged Van Buren not to listen, telling him that the circular needed time to work. This financial crisis gave the Whigs a major issue to rally around as they geared up to take the White House in 1840.

As the nation tumbled into economic depression, Van Buren continued to execute the Indian Removal policies that Jackson had started. In 1838, Van Buren directed General Winfield Scott (1786-1866) to oversee the removal of any Cherokee who had not yet left their homes in the Southeast and moved to the lands allocated to them in Oklahoma. That summer, thousands of Cherokee were stuffed into internment camps, with as many as 20,000 of them later forced to go west as part of the infamous Trail of Tears. Around 4,000 Cherokee died on the Trail of Tears, and the Van Buren administration oversaw the forced relocation of many other Native American nations as well. Van Buren also oversaw the continuation of the Second Seminole War (1835-1842) in Florida, which has been regarded as the longest and costliest of the US-Indian wars. Van Buren's handling of both Indian Removal and the Seminole War added to his unpopularity.

Among the other events of Van Buren's presidency were a border dispute with Canada called the Aroostook War, in which Americans and Canadians clashed along the Maine-New Brunswick border. Van Buren sent General Scott to restore peace, and the issue was eventually settled in the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842. In 1839, Van Buren courted the proslavery vote by siding against the African slaves who had mutinied and seized control of the slave ship La Amistad only to be arrested in American waters. Van Buren's government pressed for these men to be returned to slavery while lower courts ruled that they were legally free. The case was argued up to the Supreme Court, where it was decided that the Africans were free and should be returned home. A final significant facet of Van Buren's presidency was his refusal to entertain the prospect of annexing Texas, fearing that such an act would provoke an unjust war with Mexico. This was his only major departure from Jacksonian policy.

Re-election Loss & Post-Presidency

In 1840, Van Buren ran for re-election against the Whig candidate, William Henry Harrison (1773-1841), a celebrated war hero propped up as a foil to Jackson. The Whigs ran a campaign blaming Van Buren for the Panic of 1837, referring to the president as 'Martin Van Ruin' and singing campaign songs like 'Van, Van, Van is a Used-up Man'. This resonated with voters who were frustrated about the economy, while the Democrats' attempts to paint Harrison as an old man past his prime did not stick. Ultimately, Harrison won by a margin of 234 to 60 electoral votes. At the end of his term in March 1841, Van Buren returned home to his estate of Lindenwald in Kinderhook, though he did not intend to slip into a quiet retirement. Instead, he kept a close eye on political developments and often met with Democratic leaders, looking for a chance to make a comeback.

Before long, it seemed as if an opportunity had arrived. Harrison died only a month into his presidency and his successor, John Tyler (1790-1862), split with the Whig Party, creating chaos and disunity. Sensing an easy victory, Van Buren began building up support for a presidential run in 1844. But Tyler, hoping to salvage what was left of his popularity, made the annexation of Texas the focus of his administration; suddenly, any hopeful presidential candidate was expected to give his views on the subject. Though he knew that annexation was popular within the Democratic Party, Van Buren was forced to publicly admit that he opposed annexation, since it would likely lead to war with Mexico. This ultimately lost him the support of Jackson, who wanted annexation and still commanded much influence within the Democratic Party. At the Democratic National Convention in May 1844, Van Buren lost the nomination to the dark-horse candidate James K. Polk (1795-1849). Polk won the presidential election and oversaw the admission of Texas as the 28th state. Much as Van Buren had feared, this led to the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), an unpopular conflict that was regarded by many as an unjust invasion.

In 1848, Van Buren ran for president once again, this time as the candidate of a third party called the Free Soil Party. His supporters were an odd mixture of anti-slavery Democrats, called 'Barnburners', and Whigs. He never picked up much traction and lost the election after receiving only 10% of the vote. Van Buren never ran for public office again. He remained at Kinderhook, watching as sectional divisions over the issue of slavery tore the nation apart and led to the American Civil War (1861-1865). Though he had initially opposed the anti-slavery Republican Party as too radical, Van Buren supported the Union and came to believe in the policies of Republican President Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865). He would never see the end of that conflict, however, as he died of asthma at home on 24 July 1862, at the age of 79. Though he is barely remembered by many Americans today, Van Buren played a major role in shaping the modern US political system and was one of the most influential figures of the Jacksonian Age.