The Konark or Konarak Sun temple is dedicated to the Hindu sun god Surya, and, conceived as a giant stone chariot with 12 wheels, it is the most famous of the few sun temples built in India. It is located about 35 km northeast of the city of Puri on the coastline in the state of Odisha (earlier Orissa). It was built c. 1250 CE by King Narasimhadeva I (r. 1238-1264 CE) of the Eastern Ganga dynasty (8th century CE - 15th century CE). The temple in its present state was declared by UNESCO a World Heritage Site in 1984 CE. Although many portions are now in ruins, what remains of the temple complex continues to draw not only tourists but also Hindu pilgrims. Konarak stands as a classic example of Hindu temple architecture, complete with a colossal structure, sculptures and artwork on myriad themes.

Eastern Ganga Dynasty & Odisha Temple Architecture

The Eastern Gangas established their kingdom in the Kalinga region in eastern India (present-day Odisha state) at “the beginning of the eighth century CE” (Tripathi, 368), though their fortunes rose from the eleventh century CE onwards. The greatest king of this dynasty was Anantavarman Chodaganga (1077 - 1147 CE), who ruled for about 70 years. He was not only a formidable warrior but also a patron of arts, and greatly favoured temple building. The great temple of the god Jagannatha at Puri, begun by him, 'stands as a brilliant monument to the artistic vigour and prosperity of Orissa during his reign' (Majumdar, 377). His successors continued the tradition, with the most notable being Narasimhadeva I who not only completed the construction of the Jagannatha temple but also the temple at Konarak.

The Architecture at Konarak

The word 'Konark' is a combination of two Sanskrit words kona (corner or angle) and arka (the sun). It thus implies that the main deity was the sun god, and the temple was built in an angular format. The temple follows the Kalinga or Orissa style of architecture, which is a subset of the nagara style of Hindu temple architecture. The Orissa style is believed to showcase the nagara style in all its purity. The nagara was among the three styles of Hindu temple architecture in India and prevailed in northern India, while in the south, the dravida style predominated and in central and eastern India, it was the vesara style. These styles can be distinguished by how features such as ground plan and elevation were represented visually.

The nagara style is characterized by a square ground plan, containing a sanctuary and assembly hall (mandapa). In terms of elevation, there is a huge curvilinear tower (shikhara), inclining inwards and capped. Despite the fact that Odisha lies in the eastern region, the nagara style was adopted. This could be due to the fact that since King Anantavarman's domains included many areas in northern India as well, the style prevalent there decisively impacted the architectural plans of the temples that were about to be built in Odisha by the king. Once adopted, the same tradition was continued by his successors too, and with time, many additions were made.

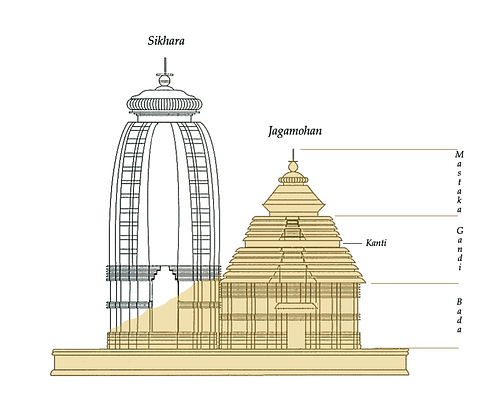

The main characteristics of the Orissa style are primarily two: the deul or the sanctum housing the deity covered by a shikhara, and the jaganamohana or the assembly hall. The latter has a pyramidal roof built up by a secession of receding platforms known as pidhas. Both structures are squares internally and use a common platform. The exterior is variegated into projections known in this style as rathas or pagas which create effects of light and shade. Many temples built in this style show their own peculiar variations, and Konarak is no exception.

The style here follows the architecture of the Lingaraja temple built around 1100 CE in the present-day city of Bhubaneshwar, the state capital of Odisha, and known locally as the Khakhara style. In this design, the temple is situated within a large quadrangular court enclosed by massive walls and with a massive gate in the east. There are multiple halls dedicated to various activities like dancing, serving meals, gatherings, etc., within this complex along with the sanctum and with lofty towers. Konarak 'excels the Lingaraja in the nobility of its conception and the perfection of its finish. Grand and impressive even in its ruin, the Konarak temple represents the fulfillment and finality of the Orissan architectural movement' (Publications Division, 21).

The Konarak temple, built entirely in stone, is in the form of a colossal chariot with twelve pairs of lavishly-ornamented wheels, drawn by seven richly-caparisoned, galloping horses. The wheels have been carved against the sides of the “chariot”. The conception of this temple in the form of a chariot has mainly to do with Hindu beliefs regarding Surya that he is usually found on a chariot pulled by seven horses. Thus, the depiction of a chariot invariably became part of any artistic creation related to the sun god in India. The 12 pairs of wheels represent the 12 months of the year.

The deul including the magnificent shikhara has been lost with time. Today, only the jaganamohana and the pillared bhoga mandapa (refectory hall), also known as the nata mandapa (dancing hall) owing to the numerous sculptures of dancers and musicians on its walls and pillars, in front, remain.

Legend

Konarak is mentioned in ancient Hindu texts having mythological significance like the Puranas. Konaditya (Konarak) was believed to be the most sacred place for the worship of Surya in the entire Odisha region. In gratitude for healing his skin ailment, Samba, one of the god Krishna's many sons, erected a temple in the honour of Surya. He even brought some Magi (sun-worshippers) from Persia, as the local Brahmanas (the priestly class among the Hindus) refused to worship Surya's image. This story was associated with a sun temple in north-western India, but was shifted to Konarak in order 'to enhance the sanctity of the new centre by making it the site of Samba's original temple' (Mitra, 10). Konarak, over time, had emerged as an important site for sun worship and hence, a mythological background was considered necessary to increase its importance for devotees.

A Royal Dream

The exact reason for the building of the temple by Narasimhadeva is not known. Historians have surmised that the king did so either to express his gratitude for a wish-fulfilment or to commemorate a conquest. Also, he could have done it simply to show his devotion to Surya, but not without adding in his own view of life as seen from a king's perspective. This is proven by the sculptures depicting royal activities, including hunts, processions and military scenes, which 'emphasises the fact that the Sun Temple is the realisation of the dazzling dream of an ambitious and mighty king, secular to the core and with an immense zest for life' (Mitra, 27). Even in the sanctuary, the holiest spot in any Hindu temple, sculptures in niches depict secular themes; 'the themes of the niches inside the pavilions, with a single exception where a preacher-like figure is seen seated in meditation, centre on the life of a king in the palace. Thus, in one niche, an armed king is seen fondly regarding his reflection in a mirror' (Mitra, 56).

Construction

Three kinds of stone were used in the temple's construction - chlorite, laterite and khondalite. Khondalite (though of poor quality) was used throughout the monument while chlorite was restricted to doorframes and to a few sculptures, while laterite was used in the foundation, the (invisible) core of the platform and in the staircases. None of these stones was available near the site and so material was brought long distances. The stone blocks were lifted possibly by the means of pulleys, wooden wheels or rollers and then set into place. The fitting and finishing were done so smoothly that the joints could not be seen.

Sculptures

During Narasimhadeva's reign, Eastern Ganga art reached its zenith. At Konarak, therefore, the sculptures display these heights; 'Nowhere is this era of Kalinga sculpture better represented than in the gigantic and miniature carvings which decorate the jaganamohana of the stone temple at Konarak' (Publications Division, 77). Every bit of space available has been covered by the sculptors and with what appears as an endless variety of themes, with figures indulging in song and dance and in activities related to kama (Sanskrit: “desires and sensual enjoyment”). There are also depictions of mythical beings, birds and animals, besides floral and geometrical motifs. The designs were carved after the stones had been set into place.

Panels represent King Narasimhadeva in various roles - as a scholar reviewing literary works being presented to him by poets, as enjoying himself on a swing in his palace, as a great archer, and as a deeply religious devotee. These are made from pink and green khondalite (these panels can also be viewed at the National Museum, New Delhi). These depictions dominate to such an extent that it appears that 'the sculptors were so busy highlighting the myriad facets of royal life that they had very little scope to record the daily life of the common man' (Mitra, 27).

A colossal idol of Surya in the southern niche of the sanctuary is a characteristic sculpture of this temple. It is also one of the very few sculptures in India which show a god wearing boots. This can be attributed to Central Asian influence on Indian art, owing to the reign of Scythian-origin dynasties of ancient India. The god is depicted standing on his chariot drawn by seven horses. The entire sculpture stands on a chlorite pedestal and is made from a single piece. It is 3.38 metres high, 1.8 metres wide and 71 cm thick.

The sun god is seen wearing a short lower garment (antariya) in the drawer style (one end of the garment drawn between the legs and tucked in the waist at the back) and many ornaments. These include a girdle at the waist, a necklace of five beaded strings with a central clasp, armlets, ear-rings and a crown. These have been carved with such intricacy that each bead and motif is clearly visible. The hair is worn in a bun on the crown of the head. A halo is seen around the head, with tongues of flames protruding outwards. He holds lotus stalks in both his hands and is surrounded by several attendant figures, including celestial dancers and the king offering obeisance along with his family priest.

Pairs of animals were also made to guard the three staircases of the porch in different directions, and are regarded as masterpieces of the sculptural art of the Odisha region. These include two rampant lions standing on crouching elephants in the east, gaily decorated and harnessed elephants to the north and two beautifully caparisoned warhorses to the south. The elephants and horses have since been re-installed on new pedestals, only a few metres distant from the original locations, and now face the porch. The lions-on-elephants now lie to the front of the eastern stairs of the bhoga-mandapa. Though covered with plaster, the original colour of these sculptures was dark red patches of which are still visible.

One of the extant sculptures is of a warrior standing alongside one of the horses. Now headless, he sports a scabbard down his back, while a quiver full of arrows is seen tied to the saddle. The horse is seen crushing one figure under his hooves, while another lies below his body.

From Fame to Decay

Even in the medieval period, Konarak had become a famous temple and references are found in literary works. Along with the Jagannatha temple, it served as a landmark for sailors sailing the Bay of Bengal. The early Europeans traversing this sea referred to the Jagannatha temple as the 'White Pagoda' owing to its white plaster (now removed after restoration) and Konarak as the 'Black Pagoda'.

The reasons for the collapse of the deul and the shikhara are not as yet known. It is believed that it occurred due to 'the subsidence of the foundation, while others speak of an earthquake or lightning; yet others doubt if the temple was ever completed' (Mitra, 12). The main belief is that the temple crumbled gradually, as the use of poor quality khondalite led to the temple's eventual decay. Many people attribute the beginning of this process to the attack by Islamic invaders.

The image of the presiding deity or Surya has also never been found and hence it is not known as to what shape, form or size it originally was. The speculation surrounding it again gives voice to many beliefs, including its destruction or removal to the Jagannatha temple. The loss of the deity caused the temple to be neglected, eventually causing its decay.

Discovery & Restoration

James Fergusson (1808-1836 CE), the noted Scottish historian of British India who played a key role in rediscovering ancient Indian antiquities and architectural sites, visited Konarak in 1837 CE and prepared a drawing. He estimated the height of the portion still standing as being between 42.67 and 45.72 metres. By 1868 CE, the site had been reduced to a mass of stones covered by trees here and there. Fergusson wrote that a local raja (king) had removed some sculptures to decorate a temple he was building in his own fort, and that the temple itself was somehow saved from being used in building a lighthouse. Besides the raja, the 'locals were also not inactive in removing the fallen stones and taking out the iron cramps and dowels' (Mitra, 14).

Conservation activities picked up speed from 1900 CE onwards after Lt. Governor John Woodburn 'initiated the launch of a well-planned campaign to save the temple at any cost by adopting suitable measures' (Mitra, 33). Since 1939, CE the Archaeological Survey of India has been conserving and maintaining the site.

Legacy

At Konarak, 'the joy of a princely life on earth and expression of the luxury and grandeur prevailing in the royal environment are writ large everywhere' (Mitra, 27). Hence, the temple appears more as the dream of a king who wanted his name and his secular deeds immortalized, but who also wanted to prove himself a devotee, like all other Indian kings. The artisans, while showcasing this element primarily, also depicted the religious aspect well. No doubt, the Konarak temple even in its ruined state stands majestically and bears witness to the architectural and artistic skills of the period as they stood in medieval Odisha, and India in general. The building process was a continuation of centuries of temple architecture begun from the Gupta period (3rd century CE to 6th century CE). The students of art, architecture, history and archaeology can find Konarak a knowledge-rich place.

Today, this site is not only popular with tourists and pilgrims, but also serves as a venue for cultural festivals, classical Indian dance performances, etc. Thus, even today the Sun Temple continues to play its role in preserving and furthering India's immense cultural heritage.