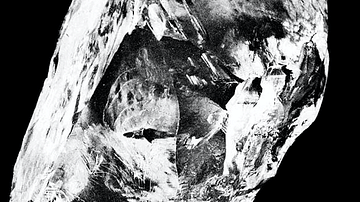

The Koh-i-Noor diamond (also Koh-i-Nur or Kūh-e Nūr) is one of the largest and most famous cut diamonds in the world. It was most likely found in southern India between 1100 and 1300. The name of the stone is Persian meaning ‘Mountain of Light’ and refers to its astounding size - originally 186 carats (today 105.6).

In its long history, the stone has changed hands many times, almost always into the possession of male rulers. Like many large gemstones, the Koh-i-Noor has acquired a reputation of mystery, curses, and bad luck, so much so, it is said that only a female owner will avoid its aura of ill omen. The stone is claimed by both India and Pakistan, amongst others, but, for the moment, the Koh-i-Noor remains irresistible to its present owners, the British royal family.

Discovery & Early Ownership

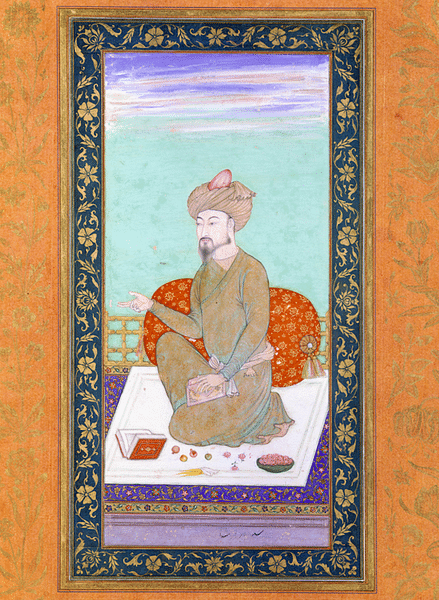

The early history of the Koh-i-Noor is very far from being as clear as the interior of the stone itself. The diamond may even be referenced in Mesopotamian Sanskrit texts of the late 4th millennium BCE but scholars are not in agreement on this. One of the problems with the Koh-i-Noor’s history is the temptation to identify it as any large diamond mentioned in ancient texts connected with events of the Indian subcontinent. The more traditional view is that the stone was most likely found in the Golconda mines of the Deccan between 1100 and 1300, although its first appearance in written records is when it belonged to Babur (1483-1530), founder of the Mughal Empire and descendant of the Mongol emperor Genghis Khan (c. 1162/67-1227). The diamond is mentioned in the Mughal emperor’s memoirs which he wrote in 1526 and was likely acquired as a spoil of war, a fate it would endure several more times over its long history and association with rulers. Babur described the stone as "worth half of the daily expense of the whole world" (Dixon-Smith, 49).

An alternative view is that Babur was talking about another stone and it was actually his son and successor who received the Koh-i-Noor as a gift from the Raja of Gwalior (a state in central India) after victory at the First Battle of Panipat in 1526. Whichever of these versions of events is correct, the result is the same, the Mughal royal family now had possession of the stone, and they wowed their court visitors by setting it in their Peacock Throne. A third view, again with the same result, is that it was not until the mid-17th century that the Mughal emperors acquired the stone following its discovery in the Kollur mines of the Krishna River.

Nader Shah & the ‘Mountain of Light’

By the 18th century we are on firmer ground in tracing the stone’s history. When the Persian leader Nader Shah (l. 1698-1747) attacked and captured Delhi in 1739, he acquired the diamond despite the then Mughal emperor trying to hide it in his turban. When he first saw the stone, Nader Shar described it as a Koh-i-Noor or 'mountain of light', and the name has stuck ever since. When Nader Shah died in 1747, the precious stone was claimed by his foremost general Ahmad Shah (l. c. 1722-1772) who founded the Durani Dynasty of rulers in Afghanistan. The Durani eventually lost their grip on power, and Shah Shujah (l. 1785-1842) was obliged to flee to India in 1813 when he gave the diamond as a gift to the ruler of the Punjab, Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1780-1839). Maharajah Duleep Singh (l. 1838-1893) inherited it when only five years old, but he was to be the last ruler of the Punjab and Sikh Empire as the tentacles of the British Empire stretched forth into northern India.

Queen Victoria

The British East India Company was the next owner of the diamond when it took over the Punjab region in 1849 CE. The peace treaty which ended the Anglo-Sikh Wars (1845-49) specified that the stone was to be given to Queen Victoria (r. 1837-1901). The diamond was then sent from Mumbai (then Bombay) to Portsmouth, England, on the HMS Medea. The stone arrived safely enough and was presented to the queen in a special ceremony in London in July 1850. The Koh-i-Noor was the central stone of a trio of diamonds set in a gold and enamel armlet or bazu-band to be worn on the upper arm. According to legend, along with the stone was a note reminding of its curse:

He who owns this diamond will own the world, but will also know all its misfortunes. Only God or Woman can wear it with impunity.

(Wilkinson, 59)

The curse story may have originated with a sensationalist news story in the Delhi Gazette which was then taken up by the Illustrated London News. The press in England was eager to add hype for the soon-to-open and already much-anticipated Great Exhibition in London in 1851 where it was already rumoured the diamond would be displayed to the public.

The queen was said to have been impressed with the size of the stone, remarking that it was "indeed a proud trophy" (Dixon-Smith, 50). She was, however, a little dissatisfied with the lack of sparkle of its ‘rose’ cut when the fashion in Europe at the time was for multi-faceted gems and there was a distinct preference for sparkle over sheer size. Nevertheless, the stone was a star attraction at the Great Exhibition, even if the satirical magazine Punch described the dullish stone as a "Mountain of Darkness" (Tarshis, 142). The queen had also worn it at the opening ceremony of the exhibition. Then, after consultation with the queen, her husband Prince Albert (l. 1819-1861), and the noted optics expert Sir David Brewster, the stone was reworked in 1852 under the direction of the royal jewellers Robert Garrard of London. The Duke of Wellington was given the honour of making the first cut, and he then stepped aside for two Dutch diamond experts to work their magic: Voorsanger and Fedder.

The reworking, which took some 450 hours to complete, gave the stone more facets as an oval-cut brilliant and dramatically reduced the weight from 186 to 105.6 carats. The stone measures 3.6 x 3.2 x 1.3 centimetres. Although now significantly smaller, the recutting did remove several flaws and made the stone much more suitable for wearing as a brooch, which the queen preferred. A famous painting of Victoria by Franz Xaver Winterhalter was commissioned in 1856, and it shows her wearing a brooch which had once belonged to Queen Adelaide (l. 1792-1849) now set with the Koh-i-Noor. This new setting was a work once again carried out by Garrard’s jewellers. On other occasions, Victoria wore the stone as part of either a bracelet or circlet for the head.

The British Crown Jewels

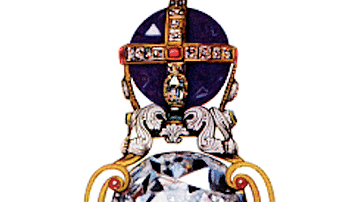

Now part of the British Crown Jewels, the Koh-i-Noor diamond has appeared in several crowns but because of its reputation as a bringer of bad luck for male wearers, it has only ever been set in the crowns of queen consorts. It was worn in the crown of Queen Alexandra (l. 1844-1925) for her coronation in 1902 and was reset in a new crown for the coronation of Queen Mary (l. 1867-1953) in 1911. Today, the diamond sparkles in the centre of the band of the Crown of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother (l. 1900-2002), the late grandmother of the present monarch, Charles III (r. 2022 - ). The Queen Mother wore this crown at her coronation in 1937. The diamond is set in a detachable mount made of platinum, the same material the rest of the crown is made from. The crown is set with another 2,800 diamonds, including the 17-carat diamond given to Queen Victoria by the Sultan of Turkey in gratitude for help during the Crimean War (1853-56). Although this square-cut stone is impressive in its own right, it is dwarfed by the massive Koh-i-Noor set directly above it. The Queen Mother wore this crown at the State Opening of Parliament each year and at the coronation of her daughter Elizabeth II in 1953. The crown and the Koh-i-Noor can be seen today alongside other items of the Crown Jewels in the Jewel House inside the Waterloo Barracks of the Tower of London.

International Calls for a Return

There have been repeated calls from the Indian government for the return of the Koh-i-Noor to its homeland. The first such request came in 1947 as the stone became a symbol of the country’s independence from British rule, which had been achieved in the same year.

Another player entered the debate in 1976 when the prime minister of Pakistan, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, called for the return of the stone to his country. Iran and Afghanistan have also laid claim to the gemstone. The calls for the Koh-i-Noor’s return to the subcontinent have by no means died down, and in 2015, a group of Indian investors even launched a legal process to have the diamond returned. As of today, though, the British royal family remain reluctant to part with this most famous and desirable of diamonds.