The germ theory, which emerged in the late 19th century, demonstrated that microscopic germs caused most human infectious diseases. The germs involved included bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, and prions. Louis Pasteur (1822-1895), a French chemist and microbiologist, and Robert Koch (1843-1910), a German physician and microbiologist, are credited with the discovery of the germ theory in the 1860s-1880s.

Regarded as the most important discovery in the history of medicine, the germ theory challenged the medical profession to reevaluate how disease was thought about, offered possibilities for both the prevention and treatment of disease, as well as the discovery and implementation of new technologies to combat disease.

Previously, doctors assumed that disease was an internal process of the human body especially Hippocrates' long-standing four humors theory notion that excesses or deficiencies of four bodily fluids (blood, phlegm, yellow and black biles) led to illness and disease. The germ theory contradicted that idea by separating the disease from the afflicted persons. Furthermore, the new theory ushered in a regimented way of classifying diseases (nosology) according to the type of microorganisms causing the disease.

Historical Theories of Disease

Prior to the discovery of the germ theory, various theories were advanced as possible explanations for illness and disease in humans. The earliest theory was the miasma theory attributed to Hippocrates (460-370 BCE), a Greek physician. Derived from the Greek word meaning pollution or "bad air", the miasma theory suggested that decomposing particles from organic materials, plants or animals, poisoned the air. Although easily detected by smell, people who inhaled the "bad air" would become ill. Additionally, planetary movements, disturbances to the Earth, poor hygiene, and polluted water often contributed to miasma. Attempts to remove waste along with cleanliness were thought necessary to improve the atmosphere to avoid infection and disease.

Aristotle (384-322 BCE), a Greek philosopher, offered the spontaneous generation of disease. It was possible, Aristotle thought, for living organisms to spring from non-living matter. Furthermore, this process, like maggots appearing from dead flesh, was a regular and natural phenomenon.

Galen (129-216 CE), a Roman physician, extended Hippocrates' earlier speculation about the imbalance of bodily fluids as the cause of disease. Galen attached each of the four humors to a particular season characterized by hot, cold, dry, and wet. For example, colds and flues occurred most often during cold and wet weather. Any change in the weather or season could upset the balance of the four humors so treatments were devised to restore said balance e.g., purges, bloodletting, enemas, and vomits. These ancient theories dominated Western medical thinking about illness until the 19th century.

Another theory of the origin of diseases referred to supernatural causes. A person's sins resulted in contracting a disease or illness as a punishment from the gods or God. Ghosts, demons, and evil spirits also possessed the ability to afflict a person with illness. Magic, divination, spells, exorcism, and various drugs were used to diagnose and treat illness. It fell to a variety of healers – shamans, priests, diviners, medicine men – to drive away the evil spirits. Illness as a punishment for sins, as well as a test of faith, was later offered by Christian theologians as an explanation for disease.

Additional theories on the origin of diseases continued to emerge. Girolamo Fracastoro (1476-1553), an Italian physician, is credited with first using the word "contagion" when describing the transmission of illness. His "seeds of disease" theory argued that disease could be spread by direct or indirect contact or over long distances through no contact at all. A German chemist, Justus von Liebig (1803-1873), one of the early founders of organic chemistry, suggested that as a result of a chemical process from decaying organic matter, disease simply emerged in the blood (the body's "chemical factory").

Groundwork for Germ Theory

Paracelsus, or Theophrastus von Hohenheim (1493-1541), a Swiss physician, and Jean Baptist van Helmont (1579-1644), a Dutch chemist and physician, were leaders in the medical revolution taking place during the Renaissance. Paracelsus, often referred to as the father of toxicology, engaged in the study of chemical substances' detrimental effects on live organisms. J. B. van Helmont, the founder of pneumatic chemistry, identified the physical properties of gases. Both men concluded that the germs causing diseases were external to humans, and once inside the human body, they would attack any of the internal organs.

More importantly, the emergence of new technologies, especially the microscope, spurred the discipline of bacteriology (a branch of microbiology that involves the identification, classification, and characterization of bacterial species). Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), a Dutch microbiologist, created the first single-lens microscope which enabled him and other researchers to see and work with microorganisms. Often referred to as the father of microbiology, Leeuwenhoek established microbiology as a scientific discipline. Microbiology not only studies the microorganisms too small to be seen by the human eye but the field also contributes to creating drugs designed to prevent and cure diseases and illnesses. Two critical elements of bacteriology emerged that underpinned germ theory:

- disease originated from microorganisms

- disease passed from one person to another through the spread of those tiny germs.

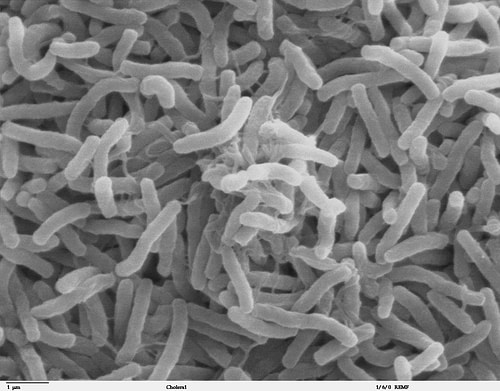

John Snow (1813-1858), a British physician, rejected the miasma theory that all diseases spread due to bad air, thus becoming an early proponent of the germ theory. In his Work on the Mode of Communication of Cholera (1849) Snow revealed that cholera was caused by a microorganism that humans swallowed and settled in their intestines, not the lungs. Specifically, due to a cholera outbreak in London in 1854, Snow identified a water pump on Broad Street as the source of the polluted water from the Thames River. Snow advised people to boil their water prior to use in order to kill the germs causing the disease (an advisory still practiced in modern public health). This example of the first practical application of the germ theory was met with rejection by Snow's peers in the medical field who did not accept the idea that invisible microorganisms caused illness.

Ignaz Semmelweis (1818-1865), a Hungarian doctor, pioneered the need for antiseptic procedures in surgery and hospital wards. Semmelweis discovered that in the maternity wards disease was being transferred through human-to-human contact, especially by doctors who were most recently in contact with corpses in the morgues, unlike the midwives who worked exclusively with pregnant and new mothers. He recommended that washing hands between examining corpses and patients and between patients dramatically reduced the incidents of puerperal sepsis ("childbed fever"), leading to much lower mortality rates.

Joseph Lister (1827-1917), a British surgeon, was another pioneer of antiseptic medicine and surgery. Lister determined that microbes caused putrefaction of wounds, recommending that not only the surgeon's hands but also surgical instruments be washed for each patient. The implementation of this single health measure caused a noticeable decrease in deaths in surgical wards.

Pasteur & Koch: Founders of the Germ Theory

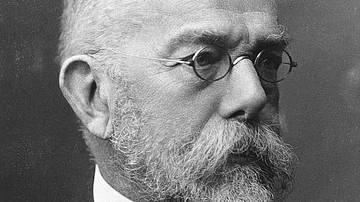

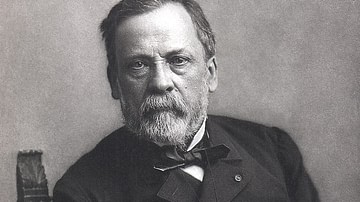

On 19 February 1878, a French chemist and microbiologist, Louis Pasteur (1822-1895), in front of the French Academy of Medicine, proposed the germ theory for the first time. Pasteur, along with his collaborators Jules Joubert (1834-1910) and Charles Chamberland (1851-1908), identified three specific characteristics of the new theory:

- particular germs create unique conditions

- particular germs cause disease, fermentation, and putrefaction

- vaccines become possible once particular germs are known

Pasteur's investigations of germs began in 1857 when French beermakers asked him to discover the reason why beer and wine spoiled. Pasteur discovered that bacteria caused alcohol to turn to vinegar. He recommended that in order to kill the germs the product be heated – this process would become known as pasteurization. These early experiments in the spirits industry demonstrated the connection between microorganisms and disease.

In 1881, Pasteur used similar methods to prove the link between anthrax and animals. In experiments with sheep, goats, and cows, Pasteur injected the animals with a vaccine that contained attenuated (weak) bacteria, which he produced by heating the anthrax germ. He injected the vaccine into sheep which caused the sheep's immune system to develop antibodies. He then injected two groups of sheep – one group vaccinated, the other not – with fully live anthrax. The vaccinated group of sheep lived; the unvaccinated group died. Pasteur's experiment thus proved that the immune system would produce sufficient levels of antibodies to protect the sheep from death.

Pasteur's experiments with rabies, begun in the early 1880s, concluded that vaccines could create immunity even if the subject was already infected. Rabies proved most challenging as the microorganism could not be seen using the microscopes of the day (visual identification requires an electron microscope, which would not be invented until the 1930s). Nevertheless, Pasteur first injected rabbits with the virus thus observing that the incubation period for developing full-blown rabies was six days. He then engaged in a series of experiments with dogs to determine the necessary strength of the vaccine, again using graduated strengths in the vaccine to produce the necessary immunity.

Pasteur's most controversial experiment on a human occurred in July 1885 on 9-year-old Joseph Meister. The boy had been bitten by a rabid dog. Over a period of 14 days, using ever stronger doses of the vaccine, Joseph survived. In a much broader experiment, the new rabies vaccine was offered to thousands of people worldwide. Pasteur was criticized for injecting people with a potentially unsafe vaccine as not all people who were bitten by rabid animals developed rabies. A ten-year study concluded in 1915, proved Pasteur to be correct as only 0.6% of 6,000 people vaccinated for rabies died. Pasteur's work on the emerging germ theory disproved the earlier theory of spontaneous generation. His experiments, especially those concerning fermentation of alcohol, established the biological underpinning of spoilage and disease. Pasteur is often referred to as the "father of microbiology" due to his groundbreaking discoveries.

Robert Koch (1843-1910), a German doctor and microbiologist and a contemporary of Pasteur, conducted similar experiments, which would contribute to the development of the germ theory. In 1876, Koch observed the rod-shaped bacteria that caused anthrax in cows. He injected some of the infected blood into mice, which contracted anthrax, thus proving that a specific germ caused a specific disease.

Koch followed his anthrax research with more definitive conclusions about tuberculosis and cholera. In March 1882, in front of a gathering of the Berlin Physiological Society, Koch demonstrated that mycobacterium tuberculosis was the cause of TB. A year later, first in Egypt, and then India, Koch concluded that vibrio cholera was the microorganism responsible for causing cholera. The bacteria were present in the human gut and primarily transmitted by drinking polluted water, which substantiated John Snow's conclusions in London 30 years earlier. Along with his students, Koch's methods, linking specific microorganisms to specific diseases, allowed for identifying a whole host of other diseases: diphtheria, typhoid, pneumonia, plague, tetanus, syphilis, and whooping cough.

Most importantly Koch developed 4 postulates for identifying particular germs as the causes of specific diseases:

- the microorganism must be present in all those humans/animals afflicted with the disease

- the microorganism must be isolated and grown outside of the diseased animal/human

- this cultured microorganism, when introduced into a healthy human/animal, must cause the disease the germ is linked to

- the cultured microorganism must be re-isolated and identical to the naturally occurring microorganism

Koch's research and conclusions all but settled the ongoing debate about germs being the cause of disease. His work also established bacteriology as a separate and unique scientific discipline.

Consequences

The discovery of the germ theory led to preventive measures, especially vaccines, and medicines, especially antibiotics, that either prevented, minimized the effects, or cured people of deadly diseases and illnesses. At the end of the 19th century, nearly 30% of all deaths were due to infection. Within a hundred years, the mortality rate dropped to 4%, especially among children. The effectiveness of vaccine programs and the application of antibiotics not only lowered the mortality rate but also helped to increase life expectancy by 30%.

Nearly as important, the germ theory boosted the public health movement by transforming both public and private hygiene. The spread of information amongst the public that microorganisms caused human diseases led to a growing sense of responsibility that people could act in various ways to prevent the outbreak and spread of disease. Hygiene campaigns identified pollution, garbage, sewers, smog, and general uncleanliness as ideal breeding grounds for deadly germs. The public came to associate dirt and germs with infection and illness. Even if the specific cause of a particular disease sometimes remained a mystery, public and personal actions were seen as being effective in preventing disease.

The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed the widespread adoption of municipal works with a focus on disease prevention. These initiatives included street sweeping, building sewers, water treatment plants, garbage hauling, and food purity regulations. On personal and domestic levels, cleanliness campaigns extended to encouraging people to keep their dwellings, their clothes, and bodies clean through regular washing as well as disposing of garbage and waste appropriately.

The germ theory, combined with the public health movement, spurred the development of "scientific housekeeping" (or home economics) at the turn of the 20th century. Sweeping, cleaning, washing, bathing, and laundering clothes became essential to the battle against germs and increased sanitation. In 1900, there were no medicines, except for vaccines against rabies and smallpox, to assist in the fight against disease, so home economics assumed a pivotal role in the prevention area of public health. According to Nancy Tomes, in Spreading the Germ Theory: Sanitary Science and Home Economics, 1880-1930, the home economics movement recognized that microorganisms were responsible for human diseases, especially those germs found in the air, water, and dirt. Good health resulted from rigorous housecleaning.

The germ theory introduced the study of bacteriology, a branch of biology, which identified, classified, and characterized the various bacteria which caused human diseases. Germ theory also promoted the study of immunology, which served to study the immune systems of all animals. The earliest concept of how the immune system helped to protect from disease can be traced back to the Plague at Athens, 430-427 BCE, when Thucydides observed people who caught the disease, survived and recovered, and then rendered assistance to others who were ill without getting sick again.

The public health movement encouraged authorities to create and later expand health departments with the twin goals of improving sanitary systems – water filtration, sewage systems, and garbage collection – while instituting regulations regarding plumbing, food preparation, and other hygiene matters. All these disease prevention measures, once combined with the home economics movement, offered the opportunity to apply science to home life, giving rise to domestic hygiene.

The advances in sanitation, hygiene, and pathology of the study of germs and diseases springing from the germ theory did more to change society than any other medical innovation. In 2000, Life magazine ranked the germ theory as the only medical advancement in its Top Ten important advancements of the previous millennium. The germ theory has come to protect and save billions of lives; lives which otherwise would have been lost to unseen germs.