Abd al-Rahman III was an Umayyad prince who reigned as Emir of Cordoba, and later Caliph of Cordoba, from 912 to 961 CE. His reign is remembered as a golden age of Muslim Spain and Umayyad rule, epitomized by his declaration of the second Umayyad Caliphate in 929 CE. He re-established one unified Muslim state in Spain and presided over the expansion of his capital at Cordoba as well as the founding of the impressive caliphal palace at Madinat al-Zahra.

Early Years

Abd al-Rahman was born at the Umayyad royal court in Cordoba on 18 December 890 CE. He was the grandson of both the Umayyad Emir of Cordoba, 'Abd Allah (r. 888-912 CE), and the King of Navarre, Fortún Garcés (r. 882-905 CE). Abd al-Rahman was just days old when his father Muhammad was assassinated by his own brother, Al-Mutarrif. 'Abd Allah had several sons who could follow him on the throne but he showed clear favoritism for his grandson Abd al-Rahman. When the emir died in 912 CE, Abd al-Rahman inherited the Umayyad throne at the age of twenty-one. Despite being Arab, the new emir was fair-skinned, blonde, and had blue eyes due to European concubines' inclusion in the family tree. According to one legend, he even dyed his beard black to match his people's image of him as an Arab Umayyad.

Abd al-Rahman had a mixed inheritance. His namesake, Abd al-Rahman I (r. 756-788 CE), had painstakingly unified Muslim Spain at the end of the 8th century CE, but after his death, the peninsula unraveled once more. Rebels such as Musa ibn Musa and Ibrahim ibn Hajjaj created their own de facto states inside the Emirate of Cordoba, especially in the north and the countryside. The Umayyads maintained their power base in the major cities of southern Spain and managed to put the rebellions down with much effort. However, frequently, these local potentates were too powerful to simply remove entirely. Instead, the Umayyad emirs held the leaders in Cordoba and had them call up their troops to support Umayyad military campaigns against other autonomous rebels. Effective Umayyad control barely extended outside of the region around Cordoba itself. It was this rather shaky political control that Abd al-Rahman III faced when he ascended the throne.

Abd al-Rahman immediately set to work. Before the year was out, rebels' decapitated heads started to dot the walls of Cordoba as fortress after rebellious fortress submitted to Umayyad arms. The greatest change was that Abd al-Rahman took personal command of the Umayyad troops, which 'Abd Allah had not done for nearly 20 years. While 'Abd Allah had to be cautious giving his generals many troops lest they betray him, Abd al-Rahman could lead the bulk of his forces himself. In addition, he began to recruit foreign mercenaries, including Turks from the East and Berbers from North Africa, whose loyalty would be unquestionable without local power bases of their own.

The greatest challenge to Umayyad authority, however, was still at large. Umar ibn Hafsun was a particularly bad thorn in the side of the Umayyads since 880 CE when he was recorded leading his first rebellion. He was brought to heel several times but continued to break out from Umayyad control until Abd al-Rahman led a full-scale campaign against him in 914 CE, besieging several of his forces and massacring the defenders of the fortress of Belda. Following this concentrated attack, ibn Hafsun finally submitted to Umayyad authority in 915 CE, at which point he controlled over 100 fortresses in Al-Andalus.

Initial Moves Against the Christian North

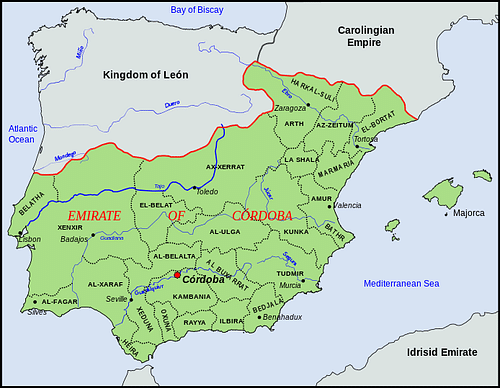

While Muslims controlled most of the Iberian Peninsula, small Christian kingdoms straddled the mountains of northern Spain. Skirmishes between the two peoples were frequent, but at this point in history the conflict was more based on territorial conflict and annual raids than the overt religious overtones of the later Reconquista. In part, this was because the Umayyad-dominated Muslim part of Spain was much more powerful than the divided Christian kingdoms.

With southern Spain temporarily pacified after the submission of ibn Hafsun, Abd al-Rahman dispatched his first campaign against the Christian kingdoms of the north in 916 CE. The Christian kingdoms had coalesced in the far north of Spain following the Muslim destruction of the Kingdom of the Visigoths in 717 CE. Instead of conquering back parts of Muslim Spain, they had gradually pushed slightly further south, occupying territory that had never really been claimed by the Muslims. In 910 CE, the territories of Asturias and Galicia were reformed into the larger Kingdom of León. Thus it was this new Kingdom of León and its king, Ordoño II (r. 910-924 CE), who were the targets of Abd al-Rahman's attack. In addition, Umayyad forces sacked Pamplona, the capital of the Kingdom of Navarre, in 924 CE.

Despite ibn Hafsun's formal submission, his sons held his territories semi-autonomously until 928 CE. After his death, three of ibn Hafsun's sons, in turn, led a resistance movement against the Umayyads from their headquarters at Bobastro. It was only in 928 CE that Bobastro and the final Hafsunid leader finally surrendered to Abd al-Rahman.

The Hafsunid rebellions illustrate the growing tension between Muslims and Christians. The Umayyad sources claim that ibn Hafsun was actually Christian, having dug up his coffin and found him buried in a Christian manner. The purpose of this was to blacken his memory as an apostate, but it also signals that Christians were indeed now viewed in a less favorable light. Christians were migrating north out of Al-Andalus in greater numbers at this time, and the 10th century CE was also the height of conversion to Islam in Al-Andalus. Furthermore, moving the Christian capital from the mountainous Oviedo to León, further south, showed increased Christian confidence and a more combative, expansionist stance.

Creating the Caliphate

Recognizing the problems of decentralized Umayyad rule, Abd al-Rahman encouraged the growth of Cordoba as a powerful center. Continuing a trend set by his 9th-century CE predecessors, Abd al-Rahman settled defeated regional potentates in Cordoba. This way he could keep an eye on them while they also added to the population and wealth of the city.

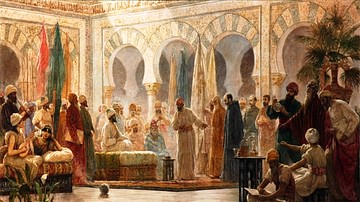

Abd al-Rahman also patronized the arts, encouraging craftsmen and building new mosques in Cordoba. The pearl of his capital, however, was the vast new imperial palace complex outside of the city: Madinat al-Zahra. Named after his favorite wife, the palace's construction began in 936 CE. It housed all of the empire's apparatus; the royal family, administrators, and soldiers. Only 7 kilometers from Cordoba, a series of roads have been found connecting the two independent, but related urban centers.

Abd al-Rahman's greatest legacy was perhaps declaring a second Umayyad Caliphate. The Umayyads had always been wary of events in North Africa, and in 909 CE, 'Ubayd Allah al-Mahdi Billah (r. 909-934 CE) declared himself the Shiite Imam and a descendant of Prophet Muhammad's daughter, Fatima. This announcement was the beginning of what would grow to be the powerful Fatimid Caliphate, and the Umayyads saw this as an enormous threat to their own regime. Abd al-Rahman had even occupied the North African town of Ceuta and its environs opposite the Straits of Gibraltar in 921 CE to block any potential Fatimid invasion.

At the same time, Abd al-Rahman was continuing to reabsorb independent Muslim warlords' fiefdoms into the Umayyad realm. He had retaken the Lower March in 929 CE with the capture of Merida and would go on to recapture Toledo in 932 CE. This was a watershed moment when Abd al-Rahman had proven that he was a credible and effective ruler but still had Muslim territories outside of his grasp.

Abd al-Rahman was descended from the Umayyad Caliphate that ruled from Damascus from 661 to 750 CE, and his announcement in 929 CE that he was the rightful Muslim caliph, the leader of Islam, was a direct affront to the Abbasids in Baghdad and the new Fatimid Caliphate in North Africa. It was an enormous power play that furthered his prestige and gave a larger rallying point for the Muslims of Spain. It also signaled that the Umayyads were not simply a break off province from the Abbasids, but were, in fact, equal, or actually better since there could only be one rightful caliph. Understandably, historians have referred to the reign of Abd al-Rahman and the raising of the Emirate of Cordoba to the Caliphate of Cordoba as a golden age of Muslim Spain.

Islamic vs. Christian Spain

Like his predecessors, Abd al-Rahman also had to face the de facto independent Muslim governors of northern Spain. The then governor of Zaragoza, Muhammad ibn Hashim al-Tujibi, became the primary target for Abd al-Rahman during the course of Umayyad campaigns in the region, led by the caliph himself, beginning in 934 CE. In one of his campaigns, Abd al-Rahman advanced on the Kingdom of Navarre, which quickly bowed to the Umayyads and allowed their boy king, García Sánchez I (r. 932-970 CE), to be crowned by the Umayyad caliph. Abd al-Rahman went on to defeat a Navarrese rebel and raid the Kingdom of León. In 937 CE, al-Tujibi surrendered Zaragoza to Abd al-Rahman. At last, Muslim Spain was back under one ruler and the Christian north had felt the power of a resurgent Umayyad state.

As demonstrated by al-Tujibi's de facto independence, Islam and Christianity were not monolithic terms. There were a variety of different Muslim and Christian powers in the Iberian Peninsula, and it was not uncommon for them to make alliances across religious lines. There was also a substantial number of Christians and Jews living in Muslim-controlled Spain. Thus, while it is expedient to describe the northern kingdoms as Christian and the Umayyad caliphate as Muslim, this was only one of their defining features, and not necessarily the predominant one. It would not be until the next century that the religious fervor of the Reconquista begins to emerge as a serious force.

Just two years after defeating al-Tujibi, Abd al-Rahman suffered a devastating defeat at the Battle of Simancas, also known as the Battle of Alhandega, against the forces of the Leónese king Ramiro II (r. 932-951 CE). The caliph's personal Koran was captured, and thousands of Umayyad soldiers lay dead. Abd al-Rahman began to ready a new force to take revenge when envoys from Garcia arrived in Cordoba in 940 CE. A peace treaty was arranged in exchange for permission to continue settling abandoned towns south of the city of León.

Simancas turned out to be just a temporary setback, however, and after 950 CE, the Umayyads dominated the Christian kingdoms of northern Spain. In 950 CE, Barcelona acknowledged the supremacy of Abd al-Rahman. In 957 CE, Umayyad forces raided the frontiers of both the Kingdom of León and the Kingdom of Navarre, and the following year both kings submitted to Abd al-Rahman in Cordoba. Abd al-Rahman even played the role of arbitrator in the Leónese civil war between Ordoño IV and Sancho I the Fat, backing Sancho in exchange for a few castles. Abd al-Rahman even sent his personal physician to treat his namesake obesity.

Social Narrative

With Muslim Spain reunified under Abd al-Rahman, historians have frequently cited his reign as the height of convivencia, where Muslims, Christians, and Jews lived in harmony. While the idea of convivencia has been exaggerated, it was certainly more tolerant than many Christian societies at this time. Jewish intellectual life did flourish in Cordoba during Abd al-Rahman's reign, and Christians and Jews were employed in some of the highest positions of the Umayyad administration, foremost among them the Jewish Hisdai ben Isaac ben Shaprut, personal secretary and doctor to Abd al-Rahman.

At the same time, ethnic tensions began to simmer in the Caliphate of Cordoba. The Arabs were the privileged upper class of Cordoban society, but there were also substantial numbers of Berbers and Saqaliba. The Berbers had been brought as troops for the early Muslim armies back in the 8th century CE, and Abd al-Rahman had recruited Berber soldiers recently for his campaigns against the Muslim rebels and Christian kings too. The term Saqaliba refers to the descendants of European slaves, some of whom had served as soldiers, members of the Umayyad harem, or even eunuchs. Abd al-Rahman had over 3,000 European eunuchs serve him as both an elite guard and protectors of his harem. Tensions began to emerge between these groups that would boil over at the turn of the century, ultimately leading to the destruction of the Caliphate of Cordoba and the Umayyad Dynasty.

Legacy

When Abd al-Rahman died in 961 CE, he had a positive legacy on which to look back. Having inherited a divided state whose power barely stretched outside the walls of Cordoba, he had united Muslim Spain and received the vassalage of all the major Christian monarchs in northern Spain. Cordoba was one of the largest, wealthiest, and most cultured cities in Europe. Finally, to top it all off, he was the Caliph (or one of three anyway), the leader of the Muslim world. The powerful Caliphate was now left to his son and heir, Al-Hakam II (r. 961-976 CE), who would strive to further his father's legacy.