For the Greeks magic (mageia or goeteia) was a wide-ranging topic which involved spells and evil prayers (epoidai), curse tablets (katadesmoi), enhancing drugs and deadly poisons (pharmaka), amulets (periapta) and powerful love potions (philtra). The modern separation of magic, superstition, religion, science, and astrology was not so clear in the ancient world. This mysterious, all-encompassing art of magic was practised by both male and female specialised magicians who people sought out to help them with their daily lives and to overcome what they saw as obstacles to their happiness.

Practitioners of mageia, the magicians, the first of whom, to the Greeks at least, were the Magi (magoi) priests of Persia, were seen not only as wise holders of secrets but also as masters of such diverse fields as mathematics and chemistry. Associated with death, divination, and evil-doing magicians were, no doubt, feared, and their life on the fringes of the community meant that practitioners were often impoverished and reliant on handouts to survive.

Magic in Greek Mythology

Magic appears in the mythology of ancient Greece and was associated with such figures as Hermes, Hecate (goddess of the moon and witchcraft), Orpheus, and Circe, the sorceress daughter of Helios who was expert in magical herbs and potions and who helped Odysseus summon the ghosts from Hades. Myths abound in tales of magic potions and curses. Just one example is Hercules, who died a horrible death after his wife Deianeira had taken the magic blood of the centaur Nessos and liberally spread it on the hero's cloak. On wearing it, Hercules was burned terribly and would later die of his wounds. Magic is also practised by many literary characters, perhaps most famously by Medea in Euripides' tragedy play of the same name.

Who believed in Magic?

Magic in the Greek world was not just prevalent in the realm of private individuals, neither was it reserved for the poor and illiterate. We know that official inscriptions were commissioned by city-states to protect their city from any possible disasters. There were also cases when, as at Teos in the 5th century BCE, the state delivered the death penalty to a man and his family found guilty of harmful magic (pharmaka deleteria). In another example, a 4th-century BCE woman by the name of Theoris received the death sentence for distributing bewitching drugs and incantations. Clearly, the authorities recognised magic as an activity capable of results and it was not simply the realm of weak-minded peasantry. Certainly, some intellectuals realised its potential for abuse, as in the case of Plato who wanted to punish those who sold spells and curse tablets. Epicurean and Stoic philosophers were another group who battled for the eradication of magic.

Amulets

At the same time as official wariness of magic, many private individuals believed in the powers of magic, and farmers, with their dependency on the vagaries of weather, were particularly susceptible to the power of amulets. These would be worn around the wrists or neck, for example, as it was hoped wearing them might guarantee sufficient rainfall that season. Greek amulets may be divided into two broad types: talismans (which brought good luck) and phylacteries (which protected). They were made of wood, bone, stone, or more rarely, semi-precious gemstones. They could also be written on small pieces of papyrus or a metal sheet and carried in a pouch or small container, or merely consist of a small bag of mixed herbs. There were also particular shapes which were viewed as auspicious to carry around in miniature form: a phallus, eye, vulva, knots, Egyptian scarab, and a small hand making an obscene gesture. Some of these amulets are still widely used today in Greece (the evil eye) and southern Italy (the cornicello horn).

Amulets were worn, for example, to cure a physical ailment, as a contraception, to win a sporting competition, to attract a lover, to keep away robbers, ward off the evil eye, or to protect the wearer from any bad magic that might be directed their way. Often to make an amulet work one had to invoke the gods (especially Hecate) or make certain utterances such as nonsense or foreign words believed to have a magical power. Amulets were not limited to persons either, for walls, houses or even entire towns could have their own amulets to protect them from any negative occurrences.

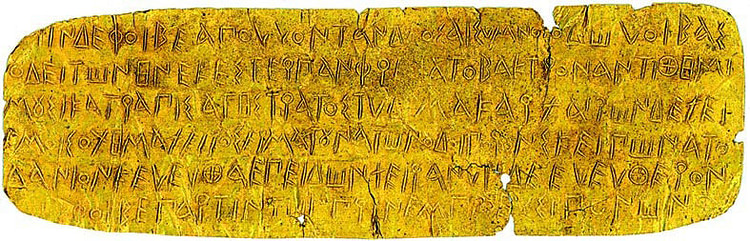

Curse Tablets

Curses (agos, ara, and euche) were a means to maintain public order through the threat of magical punishment for behaviour detrimental to the community, especially crimes such as murder. They were also seen as a way to cause harm to one's enemies. A curse tablet most often took the form of a sheet of metal (especially lead) inscribed with the curse which was then rolled or folded, sometimes nailed shut and buried in the ground, tombs or wells. Pottery sherds, papyri, and pieces of limestone were similarly inscribed. A second form was as wax or clay figurines made to resemble the victim of the curse. These have their limbs bound or twisted and were sometimes stuck with nails or buried in a miniature lead coffin.

It is interesting to note that while magicians in mythology are often female the records of curse tablets and spells typically indicate a male user. Curse tablets were mostly used as a means to settle disputes in one's favour. The first record of them dates to the 6th century BCE and they cover such topics as business deals, relationship problems, legal disputes, cases of revenge, and even athletic and drama competitions. There are instances in Greek literature where entire families and dynasties are cursed, perhaps the most famous being Oedipus and his descendants.

Magic Spells

The Egyptians had long used spells (really better described as a list of instructions to follow) and incantations written on papyri and the Greeks continued the tradition. Surviving Greek papyri concerning magic date to the 4th and 3rd century BCE. They cover such instructions as how to get over physical ailments, improve one's sex life, exorcism, eliminate vermin from the home, as parts of initiation ceremonies, or even how to make your own amulet. Recipes and poisons frequently appear too, which often used rare herbs and exotic ingredients such as spices and incense from distant Asia.