The pyramids are the most famous monuments of ancient Egypt and still fascinate people in the present day. These enormous tributes to the memory of the Egyptian kings have become synonymous with the country even though other cultures (such as the Chinese and Mayan) also built pyramids. The evolution of the pyramid form has been written about and debated for centuries but there is no question that, as far as Egypt is concerned, it began with one monument to one king designed by one brilliant architect: the Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara.

Djoser (c. 2670 BCE) was the first king of the Third Dynasty of Egypt and the first to build in stone. Prior to Djoser's reign, mastaba tombs were the customary form for graves: rectangular monuments made of dried clay brick which covered underground passages where the deceased was entombed. For reasons which remain unclear, Djoser's vizier, Imhotep (c. 2667 BCE), conceived of building a more impressive tomb for his king by stacking mastabas on top of one another, progressively making them smaller, to form the shape now known as the Step Pyramid.

Little is known of Djoser's reign. He is thought to be the son of the last king of the Second Dynasty of Egypt, Khasekhemwy (c. 2680 BCE). His mother was the queen Nimaathap and his wife the queen Hetephernepti, who was probably his half-sister. Djoser was an ambitious builder of monuments and temples. He is thought to have reigned for twenty years but historians and scholars usually attribute a much longer time for his rule owing to the number and size of the monuments he had built.

Djoser was highly respected during his reign and still, centuries after, was held in high regard as evidenced by the Famine Stele from the Ptolemaic Dynasty (332-30 BCE) which tells the story of Djoser saving the country from famine by re-building the temple of Khnum, the god of the source of the Nile River, who was thought to be holding back his grace because his shrine was in disrepair; once Djoser restored it, the famine was lifted. None of Djoser's accomplishments or building projects are as impressive, however, as his eternal home at Saqqara.

Construction

The Step Pyramid has been thoroughly examined and investigated over the last century and it is now known that the building process went through many different stages and there were a few false starts. Imhotep seems to have first begun building a simple mastaba tomb. The highest mastaba was 20 feet (6 meters) but Imhotep decided to go higher. Investigations have shown that the pyramid began as a square mastaba, instead of the usual rectangular shape, and then was changed to rectangular. Why Imhotep decided to change the traditional rectangular mastaba shape is unknown but it is probable that Imhotep had in mind a square-based pyramid from the start.

The early mastaba was built in two stages and, according to Egyptologist Miroslav Verner,

... a simple but effective costruction method was used. The masonry was laid not vertically but in courses inclined toward the middle of the pyramid, thus significantly increasing its structural stability. The basic material used was limestone blocks, whose form resembled that of large bricks of clay (115-116).

The early mastabas had been decorated with inscriptions and engravings of reeds and Imhotep wanted to continue that tradition. His great, towering mastaba pyramid would have the same delicate touches and resonant symbolism as the more modest tombs which had preceded it and, better yet, these would all be worked in stone instead of dried mud. Historian Mark Van de Mieroop comments on this, writing:

Imhotep reproduced in stone what had been previously built of other materials. The facade of the enclosure wall had the same niches as the tombs of mud brick, the columns resembled bundles of reed and papyrus, and stone cylinders at the lintels of doorways represented rolled-up reed screens. Much experimentation was involved, which is especially clear in the construction of the pyramid in the center of the complex. It had several plans with mastaba forms before it became the first Step Pyramid in history, piling six mastaba-like levels on top of one another...The weight of the enormous mass was a challenge to the builders, who placed the stones at an inward incline in order to prevent the monument breaking up (56).

When completed, the Step Pyramid rose 204 feet (62 meters) high and was the tallest structure of its time. The surrounding complex included a temple, courtyards, shrines, and living quarters for the priests covering an area of 40 acres (16 hectares) and surrounded by a wall 30 feet (10.5 meters) high. The wall had 13 false doors cut into it with only one true entrance cut in the south-east corner; the entire wall was then ringed by a trench 2,460 feet (750 meters) long and 131 feet (40 meters) wide. The false doors and the trench were incorporated into the complex to discourage unwanted guests. If one wished to visit the inner courtyard and temples, one would have needed to have been told how to enter.

The Pyramid Complex

The pyramid and its surrounding complex was designed to be stunning and inspire awe. Djoser was so proud of his accomplishment that he broke precedent of having only his own name on a monument and had Imhotep's name carved as well. The complex consists of the Step Pyramid, the House of the North, the House of the South, the Serdab, the Heb Sed Court, the South Tomb, Temple T, and the Northern Mortuary Temple. All of these, with the surrounding wall, made up a complex the size of a city in ancient Egypt. Djoser's complex, in fact, was larger than the city of Hierkanpolis at the time.

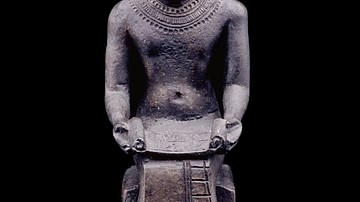

The purpose of the House of the North and House of the South is unknown but it has been speculated they represented Upper and Lower Egypt. The Serdab ('cellar') is a limestone box near the northern entrance of the pyramid where a life-sized statue of Djoser was found. This statue would have been of great importance to the soul of the king in the afterlife.

The soul was thought to consist of nine aspects and one of them, the ba (the bird-shaped image often found on tomb engravings), was able to fly from earth to the heavens at will. It required some recognizable landmark on earth, however, and this would have been the pyramid with the likeness of the king in front of it. Once the ba, high above, saw the home of its owner, it could swoop down, enter, and visit the earthly plane again. The importance of names and images of pharaohs comes into play here in that the soul needed to be able to recognize its former home (physical body) on earth in order to be at rest in the afterlife. The statue of Djoser, erected at the complex, is the oldest known life-sized Egyptian statuary extant and would have been created for this purpose as well as to remind visitors of the great king's legacy.

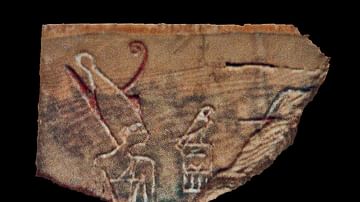

The Heb Sed Court was related to the Heb Sed Festival in which the king validated his right to rule. The festival was held in the 30th year of the king's reign and then every three years afterwards to revitalize his rule by re-enacting his coronation. This courtyard, which contains the House of the North and the House of the South, also has thirteen small chapels. The South Tomb has three carved panels depicting Djoser performing the Heb Sed ritual. This tomb is mastaba shaped and is thought to have been built to house another statue of the king. Temple T is among the most fascinating and mysterious structures in the complex. The outer facade of the building is plain and shows no efforts at ornamentation but the inside is beautifully constructed with Djed pillars (representing stability) throughout. There are intricate carvings inside as well, including one of a half-opened door which seems like an actual doorway. The meaning of this door carving is not clear but may have represented a symbolic passageway to the afterlife. The Northern Mortuary Temple, to the north side of the pyramid nearby, was used to access the subterranean passages of the pyramid which led down to the burial chamber.

The Step Pyramid

The actual chambers of the tomb, where the king's body was laid to rest, were dug beneath the base of the pyramid as a maze of tunnels with rooms off the corridors to discourage robbers and protect the body and grave goods of the king. Djoser's burial chamber was carved of granite and, to reach it, one had to navigate the corridors which were filled with thousands of stone vessels inscribed with the names of earlier kings. The other chambers in the subterranean complex were for ceremonial purposes. Historian Margaret Bunson writes:

The subterranean passages and chambers were adorned with fine reliefs and with blue faience tiles made to resemble the matted curtains of the royal residence at Memphis. The great shaft of the structure, leading to the burial chamber, was 92 feet long. The chamber at the bottom was 13 feet high, encased in granite. A granite plug sealed the passageway to the actual tomb. Mazes were also incorporated into the design in order to foil potential robbers (253).

The underground passages are vast and one of the most mysterious discoveries inside are the stone vessels. Over 40,000 of these vessels, of various form and shape, were found in two of the descending shafts of the pyramid (the 6th and 7th shafts). These vessels are inscribed with the names of rulers from the First and Second Dynasty of Egypt and are made from all kinds of stone such as diorite, limestone, alabaster, siltstone, and slate. Names of the kings Narmer, Djer, Den, Adjib, Semerkhet, Ka, Heterpsekhemwy, Ninetjer, Sekhemib, and Khasekhemwy all appear on these vessels as well as non-royal names of lesser personages.

There is no agreement among scholars and archaeologists on why the vessels were placed in the tomb of Djoser or what they were supposed to represent. The archaeologist Lauer, who excavated most of the pyramid and complex, believes they were originally stored by Khasekhemwy toward the end of the Second Dynasty and were given a "proper burial" by Djoser in his pyramid to honor his predecessors. There are other historians, however, who claim the vessels were dumped into the shafts as yet another attempt to prevent grave robbers from getting to the king's burial chamber.

Unfortunately, all of the precautions and intricate design of the underground complex did not prevent ancient robbers from finding a way in. Djoser's grave goods, and even his mummy, were stolen at some point in the past and all archaeologists found of the king was parts of his mummified foot and a few valuables overlooked by the thieves. There was enough left to examine throughout the pyramid and its complex, however, to amaze the archaeologists who excavated it.

Discovery

As with many of the monuments of Egypt, visitors and thieves explored the pyramid complex for centuries after it was abandoned but no systematic exploration was undertaken until Napoleon's Egypt campaign 1798-1801 CE. Napoleon brought a team of scholars and scientists along with his army who explored, examined, recorded, and studied the monuments of ancient Egyptian culture and who, among other accomplishments, discovered the Rosetta Stone in 1799 CE, the trilingual inscription stele which enabled French scholar Jean-Francois Champollion (1790-1832 CE) to decipher the Egyptian hieroglyphs and open up the history of ancient Egypt for the world. Napoleon's expedition was the first systematic study of the civilization and, later, led to the first western museum to install a permanent Egyptian wing at the Louvre in Paris.

Following Napoleon's artists and scientists, German, English, and Prussian archaeologists and researchers visited the Step Pyramid throughout the 19th century but no critical, scientific, examination was begun until the 1920's CE when the English archaeologist Cecil Mallaby Firth (1878-1931 CE) arrived at the site. It was Firth who, in 1924 CE, discovered the Serdab and Djoser's statue. In 1926 CE, Firth was joined on site by the French architect and Egyptologist Jean-Philippe Lauer (1902-2001 CE) who would make the major discoveries at the complex and contribute the most to modern-day understanding of pyramid construction generally and the Step Pyramid specifically.

Lauer restored, excavated, and explored the Step Pyramid and its complex for the next fifty years. He uncovered the shafts and burial chambers, found and restored the blue faience rooms, and devoted himself to bringing the ancient site back to life. Much of what one sees today in visiting the site is due to Lauer's personal efforts or those he mentored and inspired like the Egyptologist Zakaria Goneim. Lauer preserved Imhotep's grand design and brought to light the intricacies of the complex which had been overlooked by Firth and those who'd worked with him. Unfortunately, the pyramid and its grand complex today is in danger of collapse owing to an earthquake which shook the region in 1992 CE and inadequate and incompetent efforts taken to preserve and restore it.

Danger of Collapse & Preservation Efforts

A September 2014 article by Beverley Mitchell for the on-line magazine Inhabitat notes how the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities hired a company which had never worked on ancient sites before and the pyramid was in critical condition. Giant air bags were inflated under the pyramid while construction work was done but, to date, the chambers beneath the monument are still in danger of collapsing and the complex surrounding the monument is unstable. Mitchell writes, "it is a tragedy that such an important archaeological legacy could be destroyed by incompetence and lack of adequate funding" which is entirely true and should be self-evident to all; but nothing of significance has been done to preserve the pyramid or the complex in the last two years.

Miroslav Verner writes, "Few monuments hold a place in human history as significant as that of the Step Pyramid in Saqqara...It can be said without exaggeration that his pyramid complex constitutes a milestone in the evolution of monumental stone architecture in Egypt and in the world as a whole (108-109)." The Step Pyramid was a revolutionary advance in architecture but, just as importantly, it became the archetype which all the other great pyramid builders of Egypt would follow. The design of the Step Pyramid influenced the builders of the famous pyramids and their complexes in the Fourth Dynasty including the Great Pyramid of Giza, last of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Hopefully, preservation efforts at Djoser's Step Pyramid will improve in time to save this unique site for visitors to appreciate and admire in the future as they have for the past 4,000 years.