Craftsmen of the Minoan civilization centred on the island of Crete produced stone vessels from the early Bronze Age (c. 2500 BCE) using a wide variety of stone types which were laboriously carved out to create vessels of all shapes, sizes and function. The craft continued for a millennium and vessels were of such quality that they found their way to the Greek mainland and islands across the Aegean.

Techniques

Stone vases are amongst some of the earliest surviving artefacts from the Minoan civilization with examples from the early Minoan phase between 2500 and 2000 BCE. With origins in the Neolithic period and perhaps influenced in the early stages by Egyptian artists, Cretan artisans used chisels, hammers, saws and blades to work blocks of stone, sometimes also using a harder stone tool. The vessels were finished by grinding with an abrasive such as sand or emery imported from Naxos in the Cyclades. The inside of the vessel was carved out using a copper drill turned with a bow and once again using an abrasive. The drill was hollow and so the residual core of stone was then snapped off and the work finished using a second drill.

A wide variety of stone was used by Minoan craftsmen and included variegated marble, limestone, gypsum and calcite (alabaster), breccia, basalt, obsidian, rock-crystal, steatite (soapstone), schist and serpentine. In addition, design and material were often carefully matched so that elegant forms brought to the fore the natural colour variations of the stone. Most designs seem to have been copied from contemporary pottery shapes and even pottery decoration such as the Marine Style with its octopuses and shells was transferred to stone vessels.

Many fine examples of stoneware were produced across Crete including Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, Mochlos, Palaaikastro, Tylissos, Gournia and Zakros. Indeed, such was the success of Minoan artists that vessels were even exported to the Greek mainland and across the Aegean to islands such as the Cyclades.

Shapes & Designs

Popular shapes include the 'bird's nest' lidded bowl which tapered significantly at the base and was probably used to store thick oils and ointments. The form was produced over a period of 1000 years throughout Crete from 2500 to 1500 BCE. The same shape of vessel but with simple carved lines on the exterior imitating petals is known as a blossom bowl and enjoyed similar longevity in terms of popularity as the 'bird's nest' variety. The most common material for these vessels was dark grey serpentine, although, one notable lid with a carved dog is made from green schist.

As artists grew in confidence other, more ambitious and larger vessels were made such as ritual vases or rhyta which could take many forms. These were usually covered in gold leaf and were especially popular in the 15th century BCE, when the outer surfaces were, once again, often decorated with scenes carved in relief. A typical example is the Chieftain Cup in serpentine which depicts a young prince in Cretan costume, high boots and jewelled collar holding a sceptre and giving orders to one of his captains outside what appears to be a palace. Conical shapes with a single handle were popular but rhyta could also be made in the shape of animals such as lions, bulls (see below) and even shells, for example, the triton shell from Malia, which is decorated with relief scenes of demons and sealife.

Stone vases were perhaps the most common shape of all for Minoan stoneware. Tall, elegant chalices were produced with horizontal ribbing or vertical flutes, sometimes in quatrefoil form. Another type was the two-handled vase, probably imitating metal vessels, a form which is frequently depicted in Minoan frescoes. Plainer, cylindrical vases, spouted jugs and lidded boxes were also produced, as were small vessels with such limited cavities that they could only have functioned as dedicatory grave goods.

With the Mycenaean takeover of Minoan sites in the second half of the 15th century BCE the production of stoneware ceased at all sites except Knossos. Those vessels that were made tended to be larger and more functional in shape and even these died out on Crete by the early 14th century BCE.

Outstanding Examples

Perhaps the most famous example of a stone rhyton is the serpentine bull's head from the Little Palace at Knossos (c. 1600-1500 BCE) which is now in the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion. With gilded wooden horns, rock-crystal eyes and a white tridacna shell muzzle the animal is superbly rendered, capturing a life-like pose that would not be equalled in art until Classical Greek sculpture a millennium later. The head is also engraved to depict short curled hairs above the forehead and longer hairs down the cheeks. The horns have been restored (in imitation of a similar vessel from Mycenae) but one of the eyes is original and was painted behind with a black iris and red pupil. The eyes are also set inside a thin red jasper surround which gives a bloodshot effect making the bull even more realistic and threatening. The vessel was filled from the neck and liquid poured out from a small hole in the muzzle.

Another excellent example of a rhyton in stone is the serpentine Harvester Vase of Hagia Triada on Crete (c. 1500-1450 BCE). Once covered in gold leaf, this vessel, of which only the upper portion survives, is covered in relief scenes depicting a sowing festival with no fewer than 27 figures: an aged gentleman in a cloak, a singer with a rattle or sistrum of Egyptian origin, a choir and figures carrying hoes and bags of seed corn in their belts.

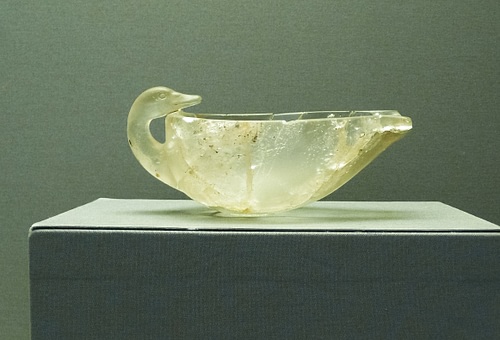

Two superb rock-crystal examples are the shallow bowl from Mycenae (but attributed to 16th century BCE Minoan Crete) which has an elegant duck's head for a handle and was perhaps originally used for storing cosmetics. The second striking rock-crystal vessel is a jug from Zakros (c. 1450 BCE) and it was also probably used to pour libation liquids in religious ceremonies. It has a separately made collar of rock-crystal with gilded ivory discs which cleverly hides the join between the neck and body. The jar has a handle made of 14 large green beads, also in rock-crystal, strung onto bronze wire. The vessel was discovered shattered into hundreds of small pieces but it has been painstakingly restored to once again win deserved admiration for the skill and artistry of Minoan stoneworkers.