Colonel Thomas Blood, a known conspirator, made an infamous but unsuccessful attempt to steal the British Crown Jewels from the Tower of London in 1671. Disguised as a clergyman, Blood and his gang swiped the royal regalia from under the nose of their keeper, but they were captured as they made their escape through the capital. Blood was mysteriously pardoned by the king, and the regalia, although a little bashed, was given a much more secure home.

The Tower

Following the execution of Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) in January 1649 during the English Civil Wars (1642-1651), the monarchy in England was abolished. A consequence of this was the breaking up of the royal regalia, which was sold off or made into coinage. Following the Stuart Restoration of 1660 and the return of the monarchy in the form of Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685), a new set of regalia was required for a new coronation. King Charles' coronation in Westminster Abbey on 23 April 1661 was a splendid affair with pomp, ceremony, and plenty of sparkle. The monarch's crown, sceptre, and orb have been used in coronations ever since.

Naturally, a secure place was required to keep these valuables until they were needed for a new coronation, and the choice was the Tower of London. Kept in the Lower Martin Tower (then called the 'Irish Tower'), the glittering collection was surely beyond the reach of any would-be thief. The reputation of the Tower of London was dark indeed in the public's imagination. Over the centuries, this was where so many traitors and criminals had been tortured. Mysterious royal murders and executions had taken place here. Its very name, simply 'The Tower', conjured up dark images of unspeakable terrors. Surely, no person would dare enter it to commit a crime. Here, if anywhere in the kingdom, the Crown Jewels were safe. Or so the authorities thought. 'Colonel' Thomas Blood had other ideas.

The Loot

The Crown Jewels in 1671 consisted of several pieces from the pre-Civil War collection. There was a gold coronation spoon and eagle ampulla, used to anoint the new sovereign with holy oil. A much bigger prize was the brand new St. Edward's Crown, the crown used at the very moment of coronation. Made of solid gold, the crown weighs 2.3 kilos (5 lbs). It is so heavy that the monarch only briefly wears it during the coronation, and it is replaced by a lighter one. The crown was set with precious stones, but most of these were only added for a coronation, a tradition that continued until 1911 when it finally gained permanent settings. During Charles' reign, the crown did have its jewels, which included the great Black Prince's Ruby (actually a balas or spinel).

The Sovereign's Sceptre (then known as the King's Sceptre) is also made of gold, as is the sovereign's orb, which is studded with pearls, precious stones, and a large amethyst beneath the cross. The Sovereign's ring was placed upon the monarch's finger and golden spurs upon their ankles in a reminder that they were the example par excellence of a medieval knight. There was, too, a jewelled sword of state for the monarch to hold during the ceremony, which may have been one of three survivors from the pre-Civil War collection: the Sword of Temporal Justice, Sword of Spiritual Justice, and the blunt Sword of Mercy (aka 'Curtana').

The Crown Jewels collection then contained, as they do now, many other pieces for use by other participants in the coronation besides the monarch. Ten ceremonial maces were made in 1661 to be carried by sergeants-at-arms during the ceremony. Each gold mace measures 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) in length and weighs 10 kilos (22 lbs). Then there are items like the gold and bejewelled Exeter Salt Cellar made to resemble a castle, which dates to 1630. This cellar and other service items were for use in coronation banquets. Not all of these items were in the same place in 1671, but the three most precious and sacred pieces certainly were: the crown, the sceptre, and the orb. These were Thomas Blood's targets.

The Thief

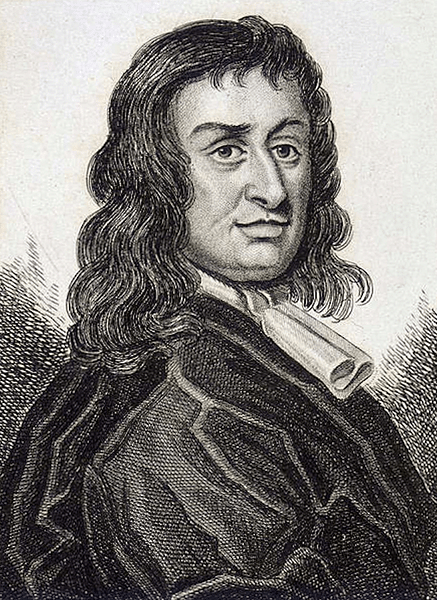

Thomas Blood was born in Sarney in County Meath, Ireland c. 1618. He was born into a Nonconformist Protestant family and became a local magistrate at the age of 21. When the English Civil Wars broke out in 1642, Blood went to England to join the Parliamentary army that sought to depose Charles I. Blood called himself a colonel, but he never rose above the rank of lieutenant. After the Restoration of the Monarchy, Blood continued to plot the downfall of his king in various unsuccessful schemes as he drifted through the dark criminal underworld of London. He became a tool of George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham (1628-1687), the arch-enemy of Charles II, and was used to spring free political prisoners and kidnap the Duke's opponents. As one diarist of the period noted of Blood: "The man had not only a daring but a villainous unmerciful look, a false countenance, but very well spoken and dangerously insinuating" (Jones, 370).

The Heist

Blood's plot hinged on one crucial fact: it had, since 1669, become possible for members of the public to visit the ground floor of the Martin Tower and see the Crown Jewels for themselves on payment of a small fee. In a rather relaxed setup, a steward, one Talbot Edwards, removed the pieces from a grill-covered cupboard and allowed the viewer to handle them. The only security was that the cupboard was otherwise kept locked, and the keeper of the jewels lived in an apartment above with his wife and daughter. That the keeper was 77 years old hardly added to the security situation.

One particularly enthusiastic pair of visitors to the Crown Jewels storeroom in the spring of 1671 was a clergyman and his wife. Indeed, they visited several times. The couple were thieves in disguise. The clergyman was really Colonel Blood, and his wife was a hired actress called Jenny Blaine. Blood's plan to steal the Crown Jewels was nothing if not audacious. He first made sure that he became friendly with Talbot Edwards, making conversation with him on each of his visits to the Tower. On the very first visit, Blaine had staged a fainting fit, which had provoked Edwards into inviting the couple to his apartments for a rest and a glass of something to drink. The odd couple returned the next day when Blood presented Edwards with some gloves as a token of his thanks for the hospitality shown the previous day. More visits followed until Blood further ingratiated himself with the hapless Edwards by suggesting a nephew of his would make a fine husband for Edwards' daughter. Edwards was enthusiastic about the match when Blood told him his nephew owned a fair strip of land in Ireland. Blood was even given a handy reconnaissance tour of the Tower by Edwards. Having ascertained the security of the Crown Jewels was rather wanting and now wholly trusted by Edwards, Blood made his move.

The day of the heist was 9 May, the time 7 am. On this particular morning, Blood was accompanied by his gang: his son Thomas Blood (using the pseudonym Tom Hunt, the "nephew"), Robert Perrot (ex-soldier and full-time criminal), and Richard Halliwell (the lookout). Outside the Tower's walls was a fourth man in charge of the getaway, one William Smith who held the horses at bay.

The three gang members, heavily armed under their cloaks, entered the Tower. The unsuspecting Edwards, who thought he was meeting his future in-laws, took out the jewels from the locked cupboard, and it was then that he was grabbed, tied up, and a piece of wood rammed in his mouth to prevent him from calling for help. Edwards put up a struggle, and he was beaten over the head with a mallet and stabbed in the stomach. Meanwhile, the gang was busy with reducing the volume of the jewels so that they could escape notice as they left the Tower. Blood, obviously not a great respecter of cultural heritage, took a hammer to the crown in order to flatten it so that it would fit under his clergyman's cloak. Perrot put the orb down his trousers. Halliwell applied a saw to the sceptre to try and cut it in half so that it could be hidden in a bag. Then, just when the most difficult part of the robbery seemed to have been completed, an extraordinary occurrence ruined everything.

The Capture

Talbot Edwards had a son, Wythe, and he had been away for ten years on military service. It just so happened that on the morning of 9 May he returned home from Flanders. The lookout Halliwell saw Wythe go to the apartment on the upper floor and rushed into the basement to tell his partners in crime. Blood's gang made a desperate dash for freedom. Just then, Edwards managed to spit out his wooden gag and raise the alarm. He shouted "Treason! Murder! The crown is stolen!" (Jones, 368). The Tower guards were immediately alerted by the commotion and gave chase, as did Wythe and his friend, a Captain Beckman. The gang, firing their pistols and scattering, made it out of the Tower, but they were pursued through the town and eventually apprehended. In the arms of his captors, Blood mused, "It was a gallant deed, although it failed" (Jones, 369).

The thieves were kept where they had committed their crime, in the Tower of London, but Blood seemed to be remarkably unconcerned at his predicament. An attempted robbery of the state's most significant, precious, and sacred property was considered by many as an act of treason, an attack on the king's person, no less. This was a crime which carried the most awful of punishments: to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. Blood was interrogated, but he said nothing. He demanded one thing only: an audience with the king. Perhaps curious to learn more of the man who would steal his crown, King Charles did indeed meet Blood.

The Reckoning

Rumours and speculation as to just why the king decided to speak with Blood have been peddled without supporting evidence ever since 1671. The most common conspiracy theory is that Blood was a spy or a double-agent, most likely for the Duke of Buckingham, that the king wished to use to gain information on the Nonconformist community and his enemies in London. Other theories include King Charles planning the whole escapade himself to pay for his lavish life at court. Reportedly, when asked by the king what he would do if his life were spared, Blood laconically replied: "endeavour to deserve it" (Dixon-Smith et al, 69).

Charles, perhaps simply impressed with his charm and audacity, pardoned Blood in an example of the king's sympathy with ambitious schemes whether they be scientific, artistic, or criminal. Blood was released from the Tower on 18 July. Even more curiously, in August, Blood received a full royal pardon for all past crimes and a grant for land in Ireland worth an annual income of £500. Contemporaries were amazed at Blood's treatment and the lack of punishment for any of the other gang members. Poor old Talbot Edwards survived his ordeal, but he struggled to gain a pension until the very end of his life.

Meanwhile, the authorities had to do some serious restoration work on the Crown Jewels. The orb had been slightly damaged in the raid, receiving a small dent. St. Edward's crown was bent back into shape. Some of the jewels set in the crown and orb had been lost who knows where in the wild chase through the streets of London. Thereafter, the Crown Jewels remained in the Martin Tower where they were kept until 1842, but they now had Yeoman warders as a permanent armed guard. By the end of the century, the Jewel Room had a strong iron door, and the regalia itself, although still on public display, was kept safely behind a massive iron grill. The daring robbery became legendary, although it was never repeated. This crime of the century has yet to tempt modern filmmakers, but it was the focus of the 1934 British film Colonel Blood.