Jade artifacts and icons are almost synonymous with the Chinese culture going back thousands of years. Jade (nephrite) was first worked into recognizable objects c. 6000 BCE during the period of the Houli Culture (c. 6500 - c. 5500 BCE). Artistic work in jade developed from that era to reach its height during the time of the Liangzhu Culture (c. 3400-2250 BCE). This period also saw the further development of the stratification of classes established early in the Yangshao Culture (c. 5000-3000 BCE) and furthered by the Hongshan Culture (c. 4700-2900 BCE). Jade, because it was so time-consuming to work, was highly prized and only the upper class could afford it.

The Liangzhu continued this social hierarchy as jade objects of their time have only been found in the tombs and graves of the wealthy; ceramics were the grave goods of the poor if they had any. Liangzhu Culture jade is characterized by extremely fine technique and attention to detail, which lends them a vitality missing from earlier cultures and would not be seen again until the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE).

An example of Liangzhu artistry is the Correya Dog, privately owned by Mr. Alfred Correya of South West England, and almost certainly dating to this period. Liangzhu jade artifacts are considered some of the finest in the world and later developments in jade work owe a great deal to the techniques perfected by this culture.

THE LIANGZHU CULTURE

The people of the Liangzhu Culture occupied an area centered around modern-day Lake Tai and stretching through Jiangsu Province, south to Hangzhou in Zhejiang Province, and eastward to Shanghai. The largest site from this period is Mojiaoshan in Zhejiang Province, measuring 2,900,000 square miles, and the second largest, Sidun, in Jiangsu Province measures at 900,000 square miles. The culture was hierarchical with stratified social classes as evidenced by burial practices and grave goods.

Scholar Elizabeth Childs-Johnson comments on this social structure and the importance of jade in distinguishing one's social status:

The Liangzhu Culture chronologically encompasses three phases, early, middle, and late. The late phase experiences large-scale site building with tiered altar cemeteries and the manufacture of classic Liangzhu jade types. Socially, the Liangzhu Culture is characterized as a series of large and small city-states or chiefdoms, ruled by those whose power was signified primarily by symbolic jades, varying in type from weapons, tools, and body ornament to ritual implements. (Speculations, 8)

The finest Liangzhu Culture jades are thought to come from this later period when the artists' technique of manipulating the nephrite would have been perfected. The Liangzhu favored homes built near waterways and archaeological evidence confirms they were adept at boating and fishing. They cultivated rice, used diamond tools in their jade work, and bred domesticated dogs and pigs.

Residential areas excavated thus far show that many homes were built on stilts, presumably as a defense against flooding, but some scholars (such as Treistman), maintain that this architectural style – as well as the ditch surrounding many villages – had as much to do with keeping pigs as anything else. The family pigs would have lived under the home and the ditch would have prevented the pigs from wandering off to become prey to wild animals.

The Liangzhu developed a highly sophisticated and complex culture which suddenly disappeared c. 2250 BCE. This was most likely due to flooding which destroyed the people's homes and cities but also helped preserve the culture. Many of the jades produced during this era have remained pristine as they were buried under silt consistent with flooding from a lake or river bed while others were preserved as grave goods.

Development of Jade Work

Jade was valued quite early by the people of China. By the time of the Houli Culture, the stone was already being worked into shapes used as protective amulets and charms. Professor Gina L. Barnes of the University of London notes how the word 'jade', which today designates a specific type of rock, is actually a misnomer and how early Chinese recognized many different types of rock and mineral which could be 'jade':

[The English word 'jade'] is commonly used to translate the Chinese word yu, traditionally designating `beautiful stones' worthy of fashioning into ritual objects and personal ornaments. (1)

Even so, Barnes also notes that Neolithic Chinese could distinguish true jade (defined as nephrite - composed of tremolite and actinolite - and jadeite) from other stones and how the jade artifacts from the Liangzhu Culture are 100% nephrite. The artisans of Liangzhu developed their skills from the overlapping culture of the Hongshan but expanded the variety of subjects to provide people with more choices.

The dominant figures of the Hongshan Culture were the pig-dragon, birds, the horse-hoof ornament, discs with cloud imagery, fish, cicadas, and tortoises. The Liangzhu developed many other subjects including the dog, pig, and the famous cong cylinders and bi discs, whose meaning and significance continue to be debated in the present.

Scholars such as Elizabeth Childs-Johnson support the theory that the cong and bi have cosmological significance, with the cong representing earth and the bi heaven. While this theory makes a great deal of sense, it is by no means accepted universally. Still, it is clear that jade objects carried significant symbolic meaning and subjects seem to have been carefully chosen as worthy of representation in the 'true jade' of nephrite. Barnes notes:

Nephrite became imbued with [great] social and cosmological significance. Jade objects were valued in China for several reasons: to symbolize rank, power, morality, wealth, and immortality. (4)

Jade was also valued because it was so difficult to work in and the creation of a single ornament would have taken considerable time. The nephrite had to be cut from cliffs with a hand saw, probably made of slate, and then smaller pieces cut from that initial slab. Scholar Judith M. Treistman describes the process:

The working of jade is not sculpture, since it is too hard to be chiseled and flaked. It must be ground and polished by abrasive sands carried in a moist or oily medium. No marks are made upon the jade by the bamboo, wood, or [other] tools that carry the abrasive. It is assumed that quartz sand was used at first and then crushed almandine garnets and eventually corundum. Bamboo was used extensively to drill through the circular bracelets and bi [discs] of Neolithic times. (94)

By the time of the Liangzhu Culture, these techniques had been developing for thousands of years. It is hardly surprising, then, that this period would produce the finest jades of the Neolithic era.

Liangzhu Culture Jade

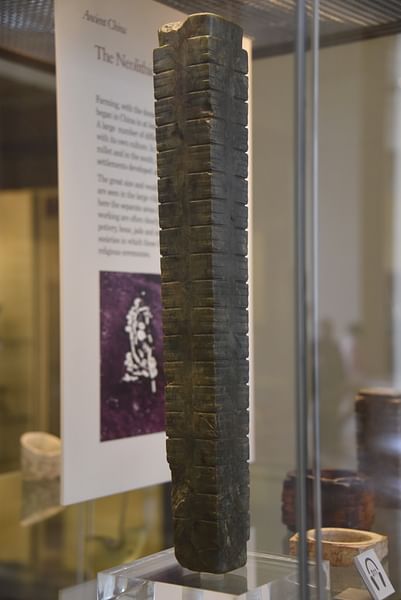

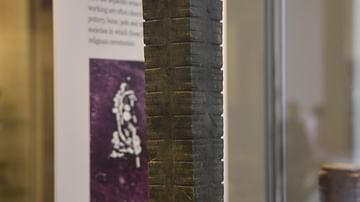

As noted, the most famous jade artifacts from the Liangzhu Culture are the pieces known as the cong and bi, a cylinder and a disc but scholars cannot agree on the significance of these artifacts. It is clear that, whatever they meant to the Liangzhu, they were of great importance as they have been found in large numbers as grave goods of the upper class. It is quite possible, as Childs-Johnson and others have argued, that they do represent the heaven and the earth since the ancient Chinese believed the earth was flat with four corners resting beneath a circular canopy of the heavens; the square and circle were symbols of each, respectively.

This theory is challenged, however, because there is no documentation from the Liangzhu Culture linking the objects directly to the concepts of earth and heaven. The earth-heaven motif is understood to have developed later during the Shang Dynasty, and those who challenge a cosmological interpretation of the cong and bi point out that one cannot interpret Neolithic artwork from the later perspective of the Shang.

The cong and bi are finely crafted jade pieces which are carefully ornamented and decorated with images. These artifacts were produced in varying sizes but always retain the same shape: the cong is a square with a circular opening and interior while the bi is a disc. The cosmological interpretation of the objects is therefore tempting but not conclusive. It is entirely possible that the people of the Liangzhu Culture attached completely different meanings to the circle and the square.

In addition to these pieces, the Liangzhu created many other fine works in jade including axes, tools, jewelry, figurines, jars, and amulets. Some of these works are decorated with the taotie motif which some scholars have interpreted as a sort of zoomorphic mask. Although the taotie design is associated with Shang Dynasty artworks, it is clearly evident much earlier in Liangzhu pieces.

One of the most interesting jades produced was the hsun chi, a serrated-jade disc with a hole in the center, which served as a stellar template. The north star was not visible during the time of the Liangzhu and so, to determine true north, the hsun chi's hole would be aligned to the Big Dipper and a sighting tube (the yu heng) would fit into the hole so that one could not only determine true north but calculate the seasons by the stars and determine the solstices. Jade axes, as noted by Childs-Johnson, were prestige items and so probably was the hsun chi which, further, would only have been of use to one educated in astronomy and astrology who would have been from the upper class.

Amulets worn on clothing or suspended from a cord worn around the neck were also produced in abundance. Although definitive religious beliefs and practices were not fully developed or codified until the Shang Dynasty, Neolithic cultures recognized that there were unseen entities more powerful than the individual and amulets were worn to protect against harmful spirits or invoke the assistance of helpful ones. A potent symbol of protection and one of the subjects rendered in jade by the Liangzhu was the dog who defended people against ghosts and other supernatural threats.

The Correya Dog

The dog is the oldest domesticated animal in China and, although used as a food source, for herding, hunting, and transporting game back to a village, it was also seen as a link between the mortal and spiritual realms. Even though the dog was domesticated and famous for its loyalty, it was still linked to the wild and acted on instinct; it was thus part of the world of humans and of the untamed sphere which people had little control over. As such, it was thought dogs could defend one against entities from other realms.

For protection on the road or going about errands, one wore an amulet, and a fine example of this kind of artifact is the Correya Dog. This piece measures 63.1 x 19.9 x 20.8 mm (2.4 x 0.78 x 0.81 inches) and weighs 42.92 grams. Laboratory testing by Gemological Certification Services, London confirms that the artifact's group is amphibole, the species is natural tremolite, and the variety is white nephrite. The group, species, and variety of this amulet are consistent with jade artifacts from the Liangzhu Culture but, of course, also with those of earlier societies such as the Hongshan, which also worked in true jade.

Although the Correya dog has not yet been dated, it lends itself to interpretation as a Liangzhu piece because of the style and subject matter. The Hongshan are not known for producing dog figures and the Hongshan style is not as delicate as the later Liangzhu. A comparison of this piece, its attention to detail and smooth finish, with a Hongshan artifact shows significant differences. A Hongshan amulet does not show the kind of sophistication of technique evident in the Correya Dog which exhibits all the characteristics seen in Liangzhu pieces.

The hole for the cord (which still retains some ancient textile colored threads) is placed unobtrusively between the dog's paws and the animal's expression is serene, as though sleeping. When worn, the amulet would have rested on its owner's body precisely like a sleeping dog which would have had two possible symbolic meanings: tranquility and protection. The sleeping dog was at peace, but when a threat appeared, it woke to action and defense.

Decline & Revival

The Correya Dog would have clearly taken the artist a long time to craft as it would have had to have been formed by repeated rubbing with abrasive for the shape and work with string or perhaps a diamond tool for the details. The GCS lab report shows there is no indication of heat used to soften the stone for work and so this piece was formed entirely by an artist working the nephrite in its natural state.

There are many other amulets from the Liangzhu Culture which adhere to this same paradigm of detailed expression and high art. Evidence of this same technique is seen in other Liangzhu jade pieces but after the culture vanishes c. 2250 BCE, so does the method until the time of the Shang Dynasty. Jade work renewed during the Shang, which produced many fine pieces, including chimes, so the Liangzhu method of jade working must have somehow been transmitted.

Jade chimes were thought to inspire wisdom as one of the five virtues inherent in the stone. The writer Xu Shen (2nd century BCE) in his work Shuo Wen, listed the eminent virtues of jade: its luster symbolized charity; its sound wisdom; its hardness courage; its smoothness equity; its translucence rectitude (Barnes, 4). Jade continued to be as highly valued during the Shang Dynasty as it had been in the time of the Liangzhu.

Throughout the eras of the Zhou Dynasty and Spring and Autumn Period (1046-476 BCE) which followed the Shang, jade production declined. During the Warring States Period (476-221 BCE) this pattern continued, and jade production only really renewed with the stability established by the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE).

Jade remained a popular stone for ornaments, amulets, and even for dresses throughout the era of the Han and continued to play a vital role in the religious and cultural life of the Chinese. The association of jade with divinity and power is famously exemplified in the revelation of the emperor Shenzong of the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE) who claimed to have received a vision from a deity he called the Jade Emperor.

Although it is generally accepted that Shenzong made this god up for his own political purposes, the Jade Emperor became the supreme deity featured in many myths and legends and, largely, because of his name. By the time of the Song Dynasty, jade was so integral an aspect of Chinese culture that linking the stone of the five virtues with the concept of imperial power was a guarantee of the people's acceptance. Just as in the time of the Liangzhu, jade was the stone of the elite and commanded the kind of awe and respect due to an emperor – or a god.