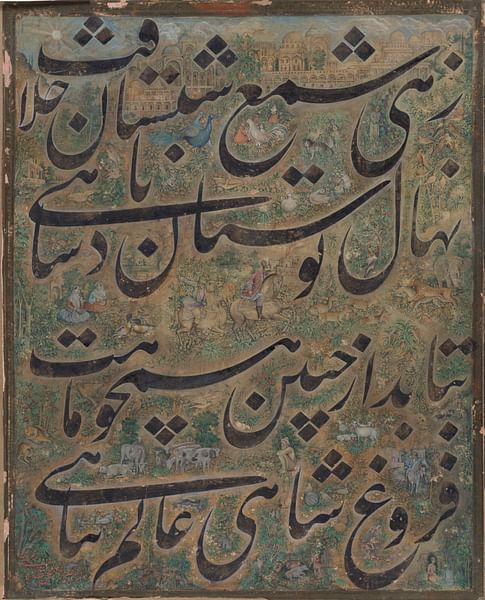

Nasta 'liq is one of the styles of Islamic calligraphy that was developed on Persian grounds by Persian calligraphers. The art of calligraphy has always held a prominent position in Persia, and its usage extends beyond the limits of the pages of books and documents to other fields of art such as architecture, pottery, metalwork, etc.

Development & History

Although the invention of nasta 'liq is attributed to Mir 'Ali Tabrizi (c. 1360-1420 CE) in the late 14th and early 15th century CE, a visual analysis of the earlier pieces of calligraphy alongside a study of the remaining documents suggests that this style had existed before. However, it is also clear that he played a crucial role in developing a set of rules and properties for the style and making it an independent and commonly used script.

Originally called naskh ta 'liq, a number of scholars believe that this style was formed out of the properties of the two earlier scripts of naskh and ta 'liq. Given the translation of ta 'liq as "hanging" in both Persian and Arabic, other scholars suggest that nasta 'liq (naskh ta ‘liq) is actually a hanging version of naskh. Having the qualities of a hanging script, nasta 'liq is thus:

A cursive script with an upper hanging quality. Individual letters or words tend to be written with an upper right to lower left slant and thus appear to hang as though suspended from a single invisible point above. (Wright, 232)

Based on visual evidence, it was the calligraphers of Shiraz who were responsible for the development of nasta 'liq and scholar Sheila S. Blair also suggests that the script underwent three stages to become fully developed, all three of which took place in Shiraz. From the 15th century, nasta 'liq became the chosen literary script used in writing Persian, in particular Persian poetry and manuscripts, while ta 'liq was used in official letters and documentation. One of the many characteristics of nasta 'liq was the faster speed of its writing compared to that of naskh. Furthermore, if one accepts the role of ta 'liq in its development, nasta 'liq was also free of the shortcomings of the former script.

Because of its impeccable elegance, balance and beauty, nasta 'liq has come to be known as the "bride of Islamic calligraphy".

It is a popular belief that the letter shapes of nasta 'liq were inspired by nature or music: the vertical strokes by trees and flowers, the round strokes by the undulations of hills and meadows or the treble and bass in singing, the elongations by fields and plains or by musical pauses, the sinuosities of letters and words by the bodily contours of animals, birds, and in particular humans, the sentence arrangement by flights of birds or clusters of flowers. (Fazaili, 603)

It has been suggested that human figures and postures are also possible sources of inspiration for the forms of the letters in nasta 'liq since in Persian poetry the beautiful features of the beloved are likened to the letters of the alphabet. In Persia, this script came to be written in two types; namely the Eastern and the Western style. Due to the Western style's sharper appearance, unusually long elongations, and not well-proportioned dimensions, it was less graceful than the former style and thus eventually disregarded in Persia. The Eastern style, perfected in the course of centuries, is the style that is currently in use today.

Nasta 'liq reached its peak and classical form during the first half of the Safavid Dynasty under calligraphers such as Mir Emad Hassani (c. 1554-1615 CE) and Sultan 'Ali Mashhadi (d. 1520 CE). In the first half of the 16th century (around 1514 CE), Sultan 'Ali Mashhadi composed an epistle in rhymed verses called Sirat al-Sutur (The Path of Writing) in which he drew a parallel between calligraphic practices and religious disciplines and included a guide to writing nasta 'liq.

In the 15th century, nasta 'liq was taken from Western Iran to the Ottoman capital, where it was confusingly known as ta 'liq, and also to India where, with some changes, it was used as the script for writing Urdu. In later centuries, the use of this script underwent constant decline and revival, but nowadays nasta 'liq is still the desired script, and many people take lessons at the Iranian Calligrapher's Association to learn it.

Famous Calligraphers

There are numerous calligraphers who were not only masters of nasta 'liq but also trained many students who continued the practice of this elegant script. Among these master calligraphers are Mir 'Ali Tabrizi, Sultan 'Ali Mashhadi, and Mir Emad Hassani who have already been mentioned, as well as Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor (c. 1829-1892 CE).

Also known as Qodwat al-Kottab (the chief of the scribes), Mir 'Ali Tabrizi was a Persian calligrapher active during the Timurid era. As noted, some scholars have named him the father (inventor) of nasta 'liq, while others believe that he merely gave the script a fixed set of rules and properties. Either way, his role in the development of nasta 'liq as an independent and commonly used script remains undeniable. One of his best students was his own son 'Ubaydallah who also worked hard in guarding and expanding nasta 'liq.

Sultan 'Ali Mashhadi and Mir Emad Hassani were both active in the Safavid era, and it was by the hands of the former that the Eastern style of nasta 'liq (the Khurasani style) reached its classical form. Sultan 'Ali Mashhadi was also known as Qeblat al-Kottab (the beacon of scribes). Due to the similarity of his style to a number of his contemporary calligraphers and the fact that he signed his works as Sultan 'Ali (a name shared by a number of calligraphers at the time), it is at times with difficulty that his works are distinguished from others. Mir Emad Hassani elevated nasta 'liq to the height of its perfection and eliminated many of its imperfections. Because of his widespread fame, even in his own time, there existed many forgeries in his name. That being said, the original works are clearly distinguishable by the exquisite ability and skill that underlies them.

Another master calligrapher of nasta 'liq script was Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor who, after a period of decline, revived the script. Kalhor was a calligrapher of lithographic press and thus introduced a variety of new conventions that had a major impact on the aesthetics of nasta 'liq in the later half of the 19th century and rendered it more suitable for the lithographic process.

Shikasta Nasta 'liq

In the early 17th century, a cursive version of nasta ‘liq emerged, which was known as shikasta nasta 'liq (literally translating to broken nasta 'liq). Its invention is assigned to Morteza Gholikhan Shamlou (c. 1688-89 CE) and Mohammad Shafi Heravi Hosayni (c. 1587-1670 CE), and it reached its peak at the hands of Abd al-Majid Talaghani (c. 1737-1771 CE). Because the letters and words in shikasta nasta 'liq were shrunken, broken, and rarely disconnected from one another, the script was written much faster than nasta 'liq. It also replaced ta 'liq as the script used in writing decrees and documents in business offices and courts.

Shikasta nasta 'liq was particularly popular during the Qajar Dynasty (1789-1925 CE) when the art of calligraphy underwent a period of revival and several new variant scripts were developed. Originally a complex script, shikasta nasta 'liq was simplified in later periods; the secretarial style (shikasta tahriri) was the most logical simplification. Shikasta nasta 'liq is also used in other Muslim countries such as Afghanistan to a certain degree and not according to Persian norms. Among the enduring Persian masters of shikasta nasta 'liq, one could name Mirza Gholamreza Esfahani (c. 1831-1887 CE) and 'Ali Akbar Golestaneh (c. 1857-1901 CE), who also practiced nasta 'liq. Both nasta 'liq and its cursive variant, shikasta nasta 'liq continue to be practiced in modern days by master calligraphers and the students that practice the scripts under their supervision.