The Chavin civilization flourished between 900 and 200 BCE in the northern and central Andes and was one of the earliest pre-Inca cultures. The Chavin religious centre Chavin de Huantar became an important Andean pilgrimage site, and Chavin art was equally influential both with contemporary and later cultures from the Paracas to the Incas, helping to spread Chavin imagery and ideas and establish the first universal Andean belief system.

Chavin Religion

One of the most important Chavin gods was the Staff Deity, who is the most likely subject for the famous central figure on the Gateway of the Sun at Tiwanaku. Forerunner of the Andean creator god Viracocha, the Staff Deity was associated with agricultural fertility and usually holds a staff in each hand but is also represented in a statue from the New Temple at the Chavin cult site of Chavin de Huantar (see below). This half-metre figure represents male and female duality with one hand holding a spondylus shell and the other a strombus shell. Another celebrated representation from the same site is the Raimondi Stela, a two-metre high granite slab with the god incised in low relief as a non-gender specific figure with clawed feet, talons, and fangs in an image which can be read in two directions. A second important Chavin deity was the fanged jaguar god, also a popular subject in Chavin art.

Chavin religious ceremony involved multi-sensory spectacles which included blood-letting and sacrificial rituals which could be performed in public spaces accommodating up to 1,500 people or in the more restricted and exclusive environment of complex temple interiors. An important feature of the cult was a priesthood of shamans who would put themselves in trances via hallucinatory plants, such as coca leaves and certain types of cacti and mushrooms. An added aura of religious mystery was achieved with the burning of incense, priests suddenly appearing atop the temples via secret internal staircases, and a cacophony of musical sounds from singers and shell trumpets.

Chavin de Huantar

The most important Chavin religious site was Chavin de Huantar in the Mosna Valley, which was in use for over five centuries and became a pilgrimage site famed throughout the Andean region. The site is significantly placed at the meeting point of two rivers - a typical Andean tradition - the Mosna and Wacheksa. Ancient landslides left fertile terraces, and the proximity of many springs and an ample and varied supply of stone for monumental building projects ensured the growth of the site.

At its peak, the centre had a population of 2,000-3,000 and covered around 100 acres. The Old Temple dates from c. 750 BCE and is actually a complex of buildings which together form a U-shape. In the centre, two staircases descend to a circular sunken court. The walls of the buildings are lined with square and rectangular stone slabs which carry images of transformational, shamanic creatures, carved in low relief. The figures mix human features with jaguar fangs and claws and they wear snake headdresses symbolising spiritual vision.

The 4.5-metre tall Lanzón monolith takes the form of a traditional Andean foot plough and stands deep within the labyrinthine interior of the Old Temple. It shows a supernatural creature with tusks and claws which is decorated with snakes. The creature points down with one hand and up with the other, perhaps indicative of its rulership of the earthly and heavenly realms. It is thought that this monolith was perhaps the site of an ancient oracle which gave answers to the demands of pilgrims who in turn left offerings of gold, obsidian, shells, and ceramics. There are also many stone channels in the temple interior through which water would have run under pressure thus creating an impressive noise in the confined inner chambers and an evocative accompaniment to the oracle's declarations.

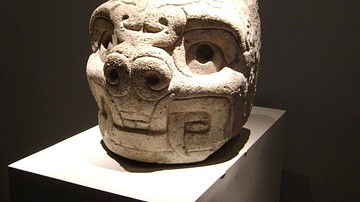

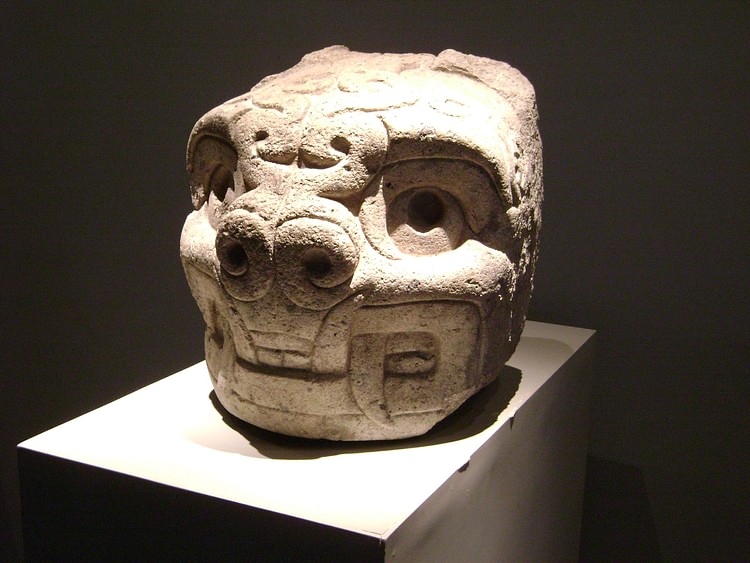

The most striking feature of the New Temple (from c. 500 BCE), which was actually an extension of the Old Temple complex, is the 100 surviving stone heads which once protruded from the exterior walls. These form a transformational series and progressively change from human to jaguar form. The temple in its new form measured 100 metres in length and reached a height of 16 metres with three stories. Its Black and White Portal entrance is flanked on either side by a single column; one carries an image of an eagle, the other a hawk representing the female and male respectively in a typical Chavin example of duality. The New Temple also contains the 2.5-metre tall Tello Obelisk which shows two caymans and snakes and may represent the creation myth. Opposite the temple a large square 50-metre-sided sunken court was constructed for ceremonial purposes, a feature which would become standard in many subsequent Andean religious sites.

Other more modest buildings at Chavin de Huantar, which often use distinctive conical-shaped adobe bricks, indicate that there was a large number of permanent residents, a social hierarchy, and centres of craft specialization. The site and the Chavin culture in general entered into decline sometime in the 3rd century BCE for reasons which remain unclear but that are probably related to several years of drought and earthquakes and the inevitable social upheaval caused by such stress. There is no archaeological evidence of a Chavin military force or of specific regional conquests. The political structures of the Chavin, then, unfortunately remain mysterious, but they did create a lasting artistic legacy which would influence almost all subsequent Andean civilizations.

Chavin Art

Chavin art is full of imagery of felines (especially jaguars), snakes, and raptors, as well as supernatural beings, often with ferocious-looking fangs. Creatures are often transformational - presented in two states at once - and designed to both confuse and surprise. Images are also very often anatropic - they may be viewed from different directions. As the art historian R. R. Stone summarises:

A strong perceptual effect, certainly calculated by Chavin artists, inspires confusion, surprise, fear, and awe through the use of dynamic, shifting images that contain varying readings depending on the direction in which they are approached. (37)

It is also noteworthy that many of the animals in Chavin imagery are from the distant lowland jungles and thus illustrate the far-reaching influence of Chavin culture, a point further confirmed by the presence at Chavin de Huantar of votive offerings from cultures hundreds of kilometres distant. The Staff Deity was another popular subject in Chavin sculpture, ceramics, and textiles. The painted cotton textiles of the Chavin are, in fact, the earliest such examples from any Andean culture and take the form of hangings, belts, and clothes.

Typical Chavin pottery is high quality and thin-walled, usually a polished red, black, or brown. The most common shape is the stirrup-spouted bulbous vessel, often with polished raised designs depicting imagery from Chavin religion. Vessels could also be anthropomorphic, typically of jaguars, seated humans, and fruits and plants. Shells were a popular form of jewellery amongst the Chavin elite and could also be carved into trumpets for use in religious ceremonies. Fine wooden bowls survive which are exquisitely inlaid with spondylus shell and mother-of-pearl, as well as turquoise. Finally, the Chavin were skilled metal workers and created objects - especially cylinder crowns, masks, pectorals, and jewellery - in sheet gold using soldering and repoussé techniques to rival any other Andean culture in their imagination and execution.